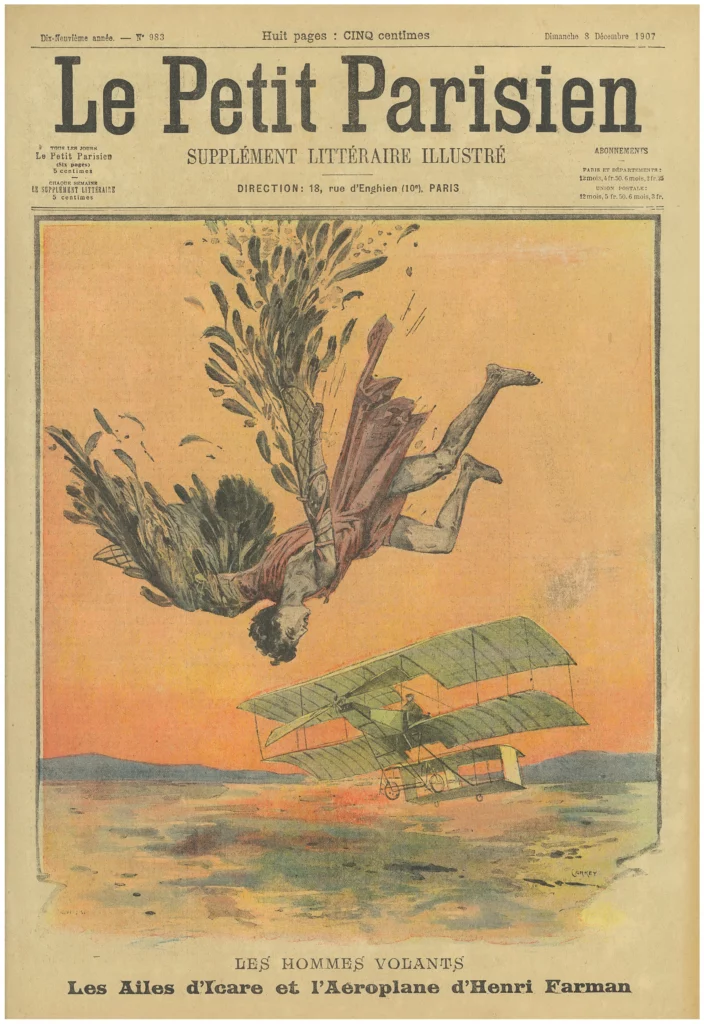

Man’s long held desire to fly can be traced through both history and myth. As far back as ancient Greece, we encounter the tale of Icarus and Daedalus.

A winged contraption constructed with feathers and wax serves as a mode of escape for Icarus and his father Daedalus. Crafted by Daedalus’ fine hand, he instructs his son to keep steady at a reasonable altitude; too low and the sea’s dampness will clog the wings, too high and the sun will melt the wax.

Icarus defies his father and flies too close to the sun and as the wax burns the men fall.

This parable on the folly of hubris serves to warn those who reach too far in arrogance and pride. However, throughout humankind’s fight to fly this sort of hubris has often urged us further forward with advances hitherto unimaginable.

World war, in particular, propelled nations into action, and they continued to test the limits of air travel through the exploits of early pioneer aviators. Many of these pilots were lost to the cause, and it is their so called ‘hubris’ that enabled the engineer, scientist and mechanic to develop modern flight.

The tale of Icarus also serves to trace mans long held fascination with flight; with the hope to emulate the birds which soared with reckless abandon overhead. It represents a desire to be free from the shackles of an earth bound existence.

Lindbergh himself stated that ‘pilots have the freedom of wind with the expanse of sky. There were times in an aeroplane when it seemed I had escaped mortality to look down on earth like a God.’[1]

It is no great wonder that the metaphor ‘free as a bird’ has become clichéd in its overuse.

The term aviation is in fact derived from the Latin avis (bird) with the suffix (-ation) and was first coined in 1863 by French pioneer Guillaume Joseph Gabriel de La Landelle.

Like Icarus and Daedalus, humanities steps toward flight began in a similar fashion. Men began to don bird like designs, jumping off towers before stretching their wings.

There proved to be little science behind these early flying contraptions and the intricacies of stability, lift and control were not yet understood. Most tower jumping attempts ended in injury or death.

The earliest recorded jump in medieval Europe dates from 852AD. Armen Firman covered his body in feathers and attached wings to his arms for his jump in Cordoba, Spain. Many continued this trend throughout the centuries. As late as 1811 Albrecht Berblinger constructed the ornithopter. This aircraft emulated the flapping wings of a bird.

As far back as the 5th century BC, China were constructing what could well be the very first man-made aircraft.

Pre-dating the ornithopter, Mozi (Mo Di) and Lu Ban (Gongshu Ban) had developed the kite.

This could be used to test the wind, measure distances, signal, communicate messages and even lift men. The popularity of the kite spread far and wide with India developing a fighter kite capable of cutting down other kites during battle.

Man carrying kites came into fruition sometime during the 6th century AD.

During this time the Chinese prince, Yuan Huangtou was captured by Gao Yang and was transported to his prison cell upon a large kite. In ancient China such kites were utilized for military and civilian purposes and were sometimes used in punishment. The man-carrying kite was introduced to Japan in the 7th century AD.

In 400 BC China utilized the rotor in flight for the very first time.

The bamboo-copter was an ancient Chinese toy and the equivalent in Europe emerged in the 14th century AD. The Chinese offered a great deal to early advances in flight, discovering that hot air rises around the 3rd century BC.

Sky lanterns could be seen listlessly floating through the night sky in celebration or during festivals. These floating entities proved terrifying to those who had never witnessed lantern flight. To these ends lanterns were used by the Chinese military around 200 AD.

Between masterpieces, Leonardo da Vinci began to ponder a rational aircraft design in the late 15th century. For the next 300 years his work would remain unknown and had no impact upon aviation developments throughout this time.

His designs were discovered in 1797, and while far more rational than tower jumping and bird feathers, they weren’t actually feasible. However, he did understand this one basic and crucial principle, that ‘An object offers as much resistance to the air as the air does to the object.’[2]

Ballooning

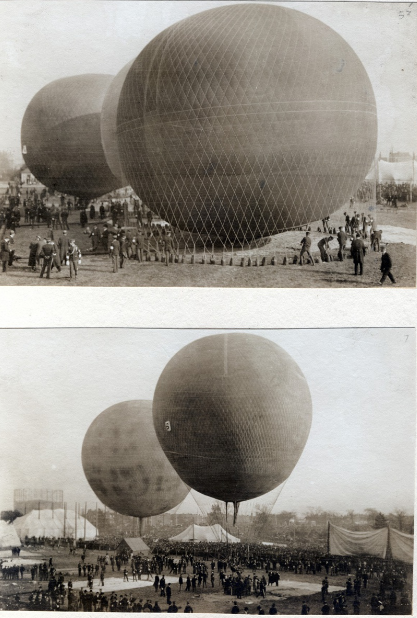

Ballooning would prove to be the next major advancement in man’s fight to fly. In 1783 a vast number of ballooning discoveries and experiments took place.

France in particular held five aviation firsts within that year. The Montgolfier brothers showcased their unmanned hot air balloon on the 4th of June. ‘Observing the suspension of clouds in atmosphere, they conceived the idea of inflating bags with vapors to cause them to rise and float. They first experimented with smoke inflation to prove the theory.’[3]

Jacques Charles and Les Freres Robert demonstrated the world’s first unmanned hydrogen balloon in Paris on August 27, 1783.

The Montgolfiers went on to astonish crowds on October 19 with the very first manned flight in a balloon safely tethered to the ground below. November 21st would see the Montgolfiers demonstrate the first un-tethered flight with human passengers.

The balloon was propelled by a wood fire with pilots Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier and the Marquis François d’Arlandes flying the aircraft for 8km.

The hydrogen balloon would once again take center stage on December 1 amidst a crowd of 400,000 Frenchmen. Jacques Charles and the Nicolas-Louis Robert piloted their own hydrogen balloon and covered a distance of 36km in 2 hours and 5 minutes.

Ballooning really took off around Europe, spreading like wildfire and sparking a major craze. Everyone wanted to fly.

Throughout the 18th century ballooning was tried and tested by many an engineer and scientist. Valiant attempts were made in determining the relationship between altitude and the atmosphere, and modern aviation owes much to this period of exploration.

The Dirigible

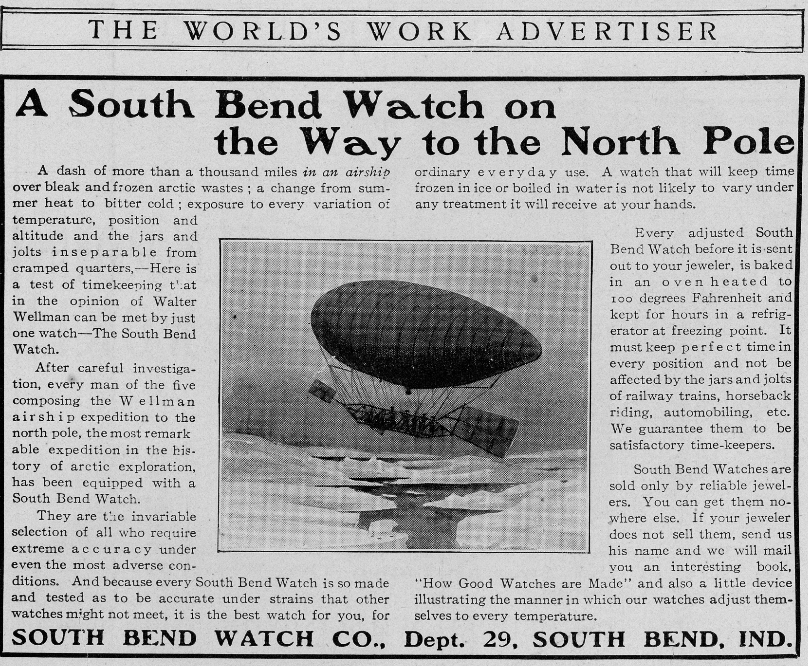

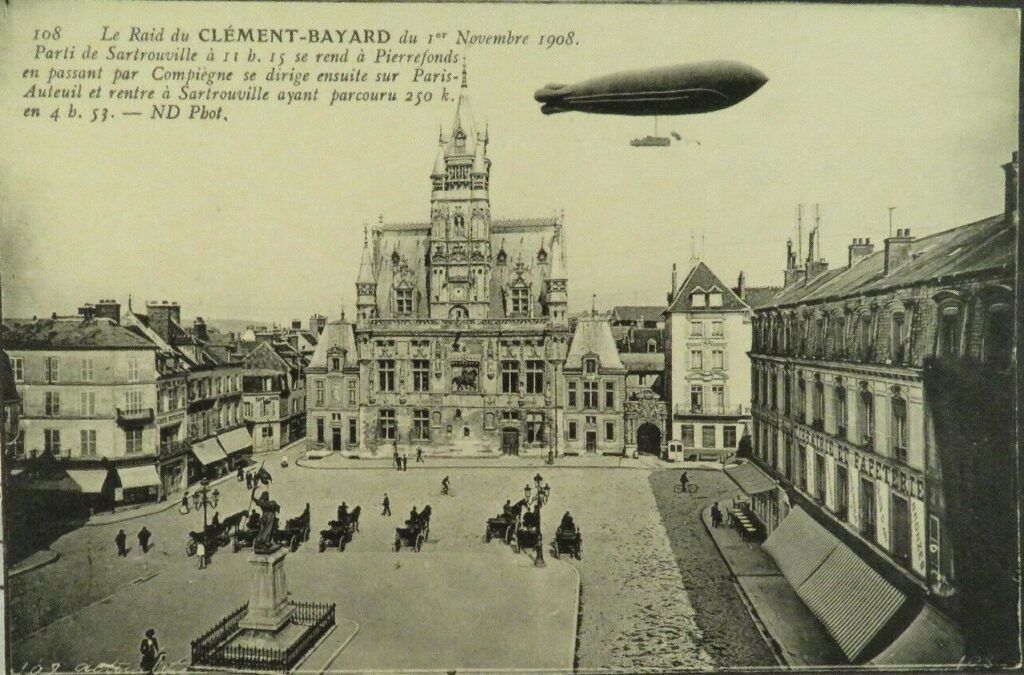

The dirigible airship, a steerable balloon, was developed throughout the 19th century. In 1852 Henri Giffard flew 15 miles in a steam engine powered airship. This would prove to be the first major advance in lighter-than-air flight in a steerable aircraft.

Charles Renard and Arthur Krebs showcased their electric powered dirigible in 1884, covering a distance of 8km in 23 minutes. This breakthrough demonstrated the feasibility of controlled flight with the aid of an electric motor.

It would eventually lead to the more reliable internal combustion engine that would revolutionize air travel.

The Union Army Balloon Corps deployed non-steerable balloons during the American civil war. There is an interesting comparison to be made with the Chinese who used lanterns during combat.

It seems that flying ships were used to invoke fear in the opposition; flight being otherworldly, perhaps even, god-like.

The infamous Ferdinand Von Zeppelin first flew in a balloon with the Union Army of the Potomac in 1863.

The early 20th century saw the balloon rise in popularity with the general British public. Ballooning was seen as a fashionable sport for the leisure class.

Privately owned balloons at this time were powered with coal gas rather than hydrogen. This material had less lifting power than its hydrogen counterpart, but coal was far more available to the British public.

The first effective combination of the balloon and internal combustion engine was invented by the Brazilian Alberto Santos-Dumont. His Number 6 blimp was flown over Paris and around the Eiffel tower on October 19, 1901.

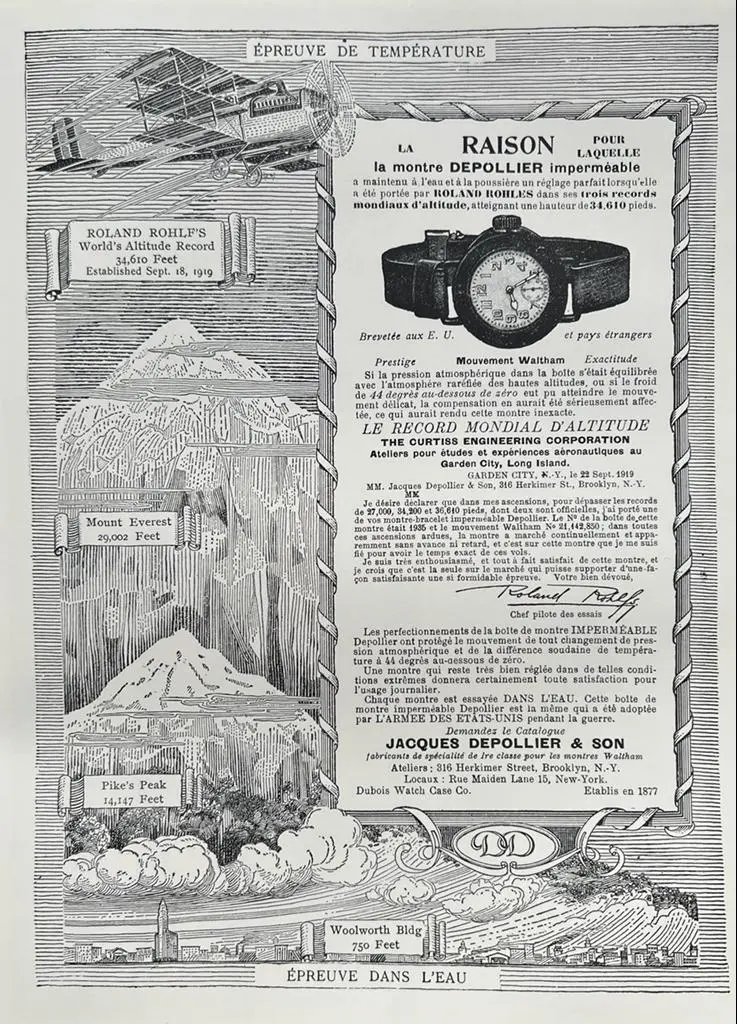

In under 30 minutes he flew this course and back to take the Deutsch de la Meurthe prize. These sorts of cash prizes would prove instrumental in aviation’s development and progress.

Throughout history these incentives have acted as a driver to technological advancement both privately and commercially. Most notably and historically memorable is that of Lindbergh’s 1927 Orteig prize accomplishment.

Cash prize incentives have even contributed to developments in space flight, with the Peter Diamandis XPrize won by entrepreneurial astronauts and engineers in 2004.

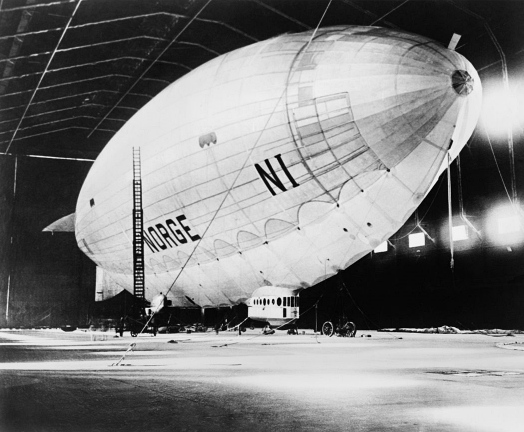

The German Count Von Zeppelin, a name synonymous with rigid airships, advocated his design throughout the latter end of 19th century. These large structures would prove far more capable in transportation of heavy loads than any rival fixed wing aircraft.

The first Zeppelin airship flew successfully for 18 minutes on July 2, 1900. The LZ 1 had to make a forced landing after a technical failure. It went on to prove its worthiness in subsequent flights where the LZ 1 broke the 6 m/s speed record set by the French made, La France airship.

However, characteristic of early aviation, it would be some time before the Count Von Zeppelin could convince investors.

Count Von Zeppelin would go on to design and build a number of dirigibles in conjunction with the Germany military up until 1910. Post 1910 he would see the Zeppelin commercialized as a passenger carrying business with Luftschiffbau-Zeppelin.

The dirigible would dominate long distance flight into the 1930’s, only superseded by the popularity of large flying boats.

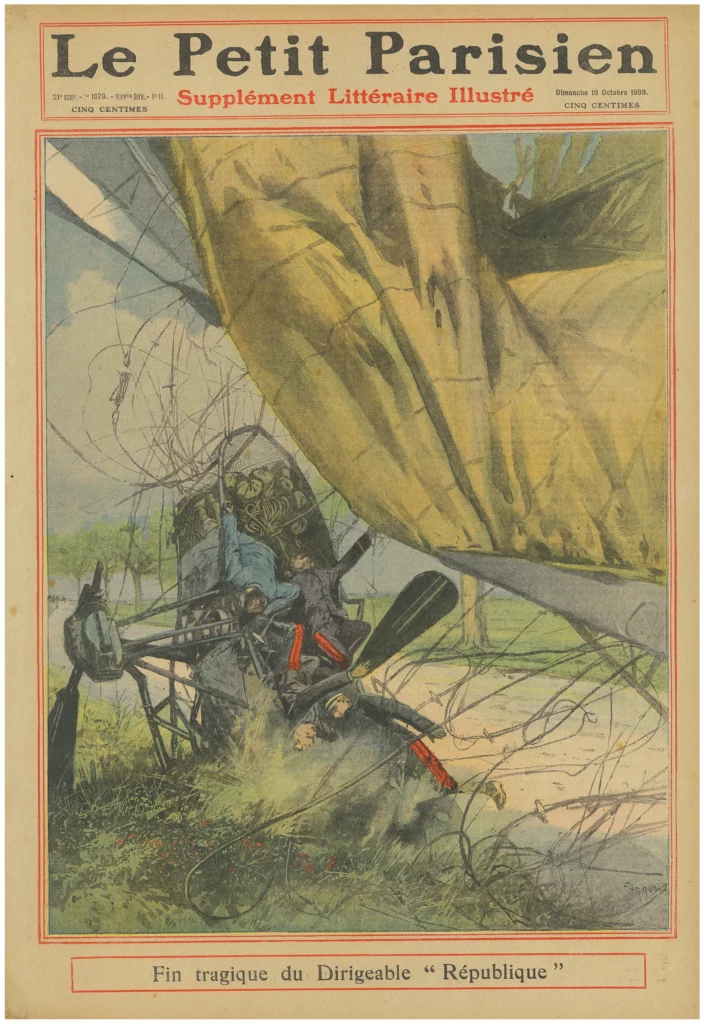

Incredibly, up until 1914 the German Aviation Association ferried 37,250 passengers on over 1,600 flights without incident. This phenomena prompted revolutionary advancements in aviation and served as the precursor to the age of air transportation. Risks and tragedy in early pioneering days were never far away, and events of such nature always made front page news.

The Zeppelin profoundly influenced developments in fixed winged aircraft as well as the feasibility of commercial aviation.

Heavier Than Air Flight – The Plane

The history of the heavier-than-air craft is long and complicated. These machines would contribute to the eventual success of the fixed winged bi-planes and mono-planes of the 20th century.

The first recorded example of a heavier-than-air plane was in 1647 in a fixed glider wing contraption that was able to carry the inventor’s cat. Italian pioneer, Tito Livio Burattini, never managed to become airborne himself; much to the dismay of his pet cat.

This early design was one of the most sophisticated early examples of an aeroplane built before the 19th century.

In 1716 Emanuel Swedenborg published Sketch of a Machine for Flying in the Air. His drawing proposed a starting point for the complexity of flight. He pontificated:

“It seems easier to talk of such a machine than to put it into actuality, for it requires greater force and less weight than exists in a human body. The science of mechanics might perhaps suggest a means, namely, a strong spiral spring. If these advantages and requisites are observed, perhaps in time to come someone might know how better to utilize our sketch and cause some addition to be made so as to accomplish that which we can only suggest. Yet there are sufficient proofs and examples from nature that such flights can take place without danger, although when the first trials are made you may have to pay for the experience, and not mind an arm or leg.”[4]

He reckoned that the principle difficulty of flight was the degree of power necessary to lift a heavier-than-air craft into the skies. His observations were astute, and while understanding that his design was not feasible, he significantly contributed to theoretical development.

In the late 18th century Sir George Cayley began to study, in earnest, the fundamental physics of flight. Cayley designed the first heavier-than-air modern aircraft in 1804.

This model glider possessed many of the principles and characteristics of planes to come, laying the foundation for the fixed wing aircraft of the 20th century. In 1809 Cayley outlined the principle issues with flight, remarking that, “The whole problem is confined within these limits, viz. to make a surface support a given weight by the application of power to the resistance of air.”[5]

Throughout his work he considered thrust, drag, lift and weight; developing a greater understanding of the four vector forces intrinsic to flight.

In 1848 a child was carried in Cayley’s new triplane glider without incident. In 1852 he designed a full-size manned glider which was successfully tested by a willing aviator in 1853. He was dubbed the ‘Father of the Aeroplane.’

Many were influenced by Cayley’s breakthroughs, and in 1842 an aerial steam carriage was conceived. While only a design, it proved crucial as the first ever propeller-force, fixed-wing aircraft.

The age of steam was an aspiring time for pioneer inventors who worked to discover the next major breakthrough. The Aeronautical Society of Great Britain was formed in 1866 as public interest in fixed winged aircraft peaked.

Francis Herbert Wenham developed Cayley’s work further and presented his paper to the fledgling Aeronautical Society. From 1858 on-wards he tested his ideas with several stacked wing gliders, discovering that long and thin wings were better equipped to take flight.

A period of serious aeronautical study began at the end of the 19th century. A group named the “gentleman scientists” dominated the field right into the 20th century. This period of study led Matthew Piers Watt Boulton to patent an aileron control system in 1868. The first wind tunnel was created in 1871.

The monoplane, a far more recognizable form of modern aircraft, was proposed 1857. The first monoplane was conceived by Félix du Temple with a design featuring a retractable undercarriage and tail plane.

It was tested in 1874 with the first successful powered flight in history. Temple’s contraption lifted itself from the earth before gliding for a short time and returning safely to the ground.

In 1856 Jean-Marie Le Bris flew his Albatross II to a height of 100 meters over a distance of 200 meters. In 1871 Alphonse Pénaud flew the first aerodynamically stable, fixed-wing aeroplane for a distance of 40 meters.

He went on to design an amphibian aircraft that was never built. The design anticipated many modern advancements in aeronautics.

Inspired by Alphonse Pénaud, Victor Tatin, French watchmaker and mechanic, flew his own monoplane in 1879. ‘Tatin’s first aeroplane model was powered by compressed air and propelled by two 4-bladed propellers.’[6]

This aircraft was the first model to take off under its own power.

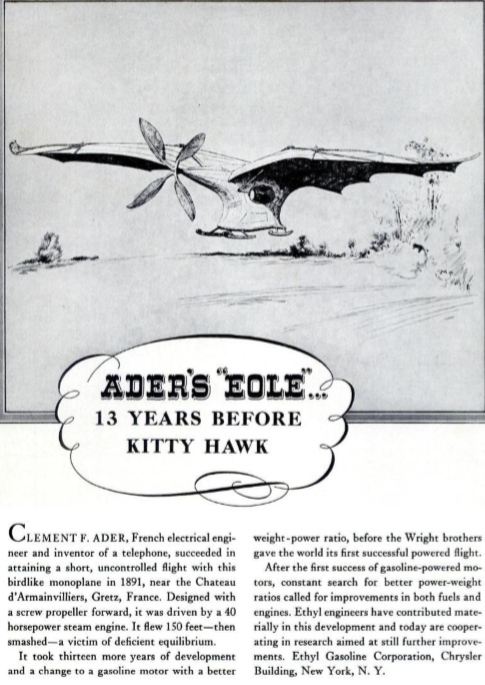

Clement Ader

1890 would see the first manned aircraft to take off under its own power, albeit in an uncontrolled sort of fashion. On October 9th Clément Ader flew for around 50 meters in his steam engine monoplane with a screw propeller in front.

The issues around flight still far outweighed any discovered solutions. As yet there were no reliable designs for a stable engine, so efforts were concentrated upon the methods of gliding.

For the last decade of the 19th century, gliding preoccupied the aviation world and a successful glider was launched in 1879 by Biot-Massia.

Massia’s break through led to Otto Lilienthal’s range of reliable gliders devised in the 1890’s. He was able to prove the feasibility of stable, un-tethered glides. He became known as the “Glider King” or “Flying Man”.

Up until the 20th century these glider designs were refined and improved upon by a number of early aviation pioneers. These heavier-than-air crafts were able to glide further in a more controlled and sustainable fashion.

Then came Dr. Samuel Pierpont Langley who set a record flight with his powered airplane model in 1896.

“He began research in aerodynamics in 1887 and made miniature flying models called ‘Aerodromes’. He built six of these, the first powered by carbonic acid gas, and the others equipped with tiny steam engines. He was credited with a record in May 1896 when one flew about 3,000 ft. over the Potomac River near Washington D.C.”[7]

He was given $50,000 by the U.S. government to build a man carrying craft in a similar fashion, but his two consecutive attempts failed. While attempting to resolve his aircraft design flaws, the infamous Wright brothers beat him to the punch in 1903.

The Wright Brothers

Wilber and Orville Wright were the first men in the history of aviation to fly a manned, mechanically powered, heavier-than-air machine.

‘This supreme achievement was accomplished first by Orville Wright on Dec. 17, 1903, at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina.

Powered with an engine of their own design, the Wright biplane had two horizontal planes with a flexible rudder which enabled the pilot to effect changes of elevation through the use of a control lever.’[8]

They made four initial successful flights during which 852 ft. was covered in 59 seconds.

The first turn in the air was made by Orville Wright on September 15, 1904, and on September 20 he made the first circle. This was a tangible example of hundreds of years’ worth of dreaming and working, culminating in a manned and maneuverable aircraft.

On October 4, 1905, the Wright plane flew an astonishing 20 and ¾ miles in 33 minutes and 17 seconds. This was the breakthrough everyone had been striving toward. From here experiment and advancement moved at a dizzying pace.

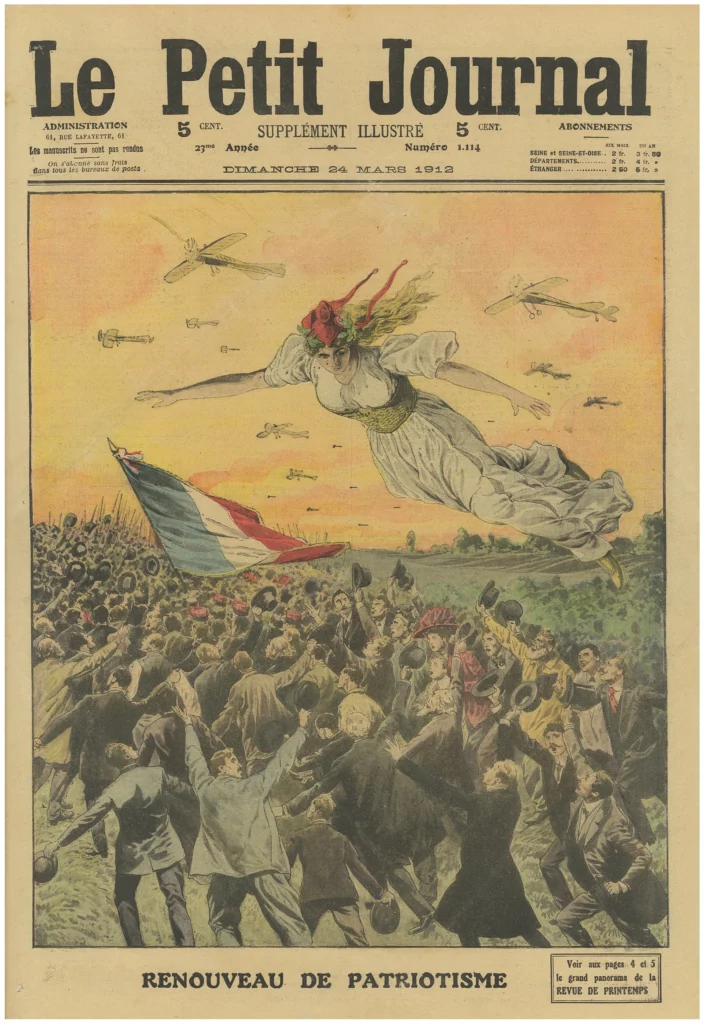

Pioneer Era

Thus followed the Pioneer Era. From 1903 – 1914 innumerable aeroplanes and airships were designed and conceived. The Wright brothers, it seemed, had cracked it and there followed a quick succession of amendments and advances.

Europe continued to experiment with unmanned aircraft throughout this time. However, in 1906 Brazilian Alberto Santos-Dumont made an extraordinary public flight in Paris in the Oiseau de proie (“bird of prey”).

On November 12, 1906, Santos-Dumont flew 220 meters in 21.5 seconds in the first world record registered by the Federation Aeronautique Internationale.

Gabriel Voisin would follow in 1907 with the first model of the Voisin biplane. Henri Farman flew a modified version of this plane on January 13, 1908, to win the Deutsch-Archdeacon Grand Prix d’Aviation prize. The flight lasted only 1 minute and 28 seconds covering a distance of 1 kilometer.

Flight was now an established technology. No longer the madcap idea of dreamers and eccentrics; aviation was recognized as a valuable fledgling technology.

Alberto Santos-Dumont developed the first mass produced aircraft with the Demoiselle monoplanes during the early 20th century.

These aircraft could be constructed in just 15 days and could travel at 120 km/h.

Wilbur Wright offered flight demonstrations to Europe in 1908. They were astonished by the Wright plane, with its ability to make decisive turns, and alterations to the Henri Farman Voisin biplane were immediately made.

In 1909 Louis Bleriot generated worldwide recognition with his flight across the English Channel on July 25. Instigated by the Daily mail who offered a $1,000 cash prize, this competition was instrumental in raising the profile of aviation.

So much so that in August 1909 some half a million people gathered for The Grande Semaine d’Aviation at Reims. This would prove to be one of the very first aviation meetings.

It didn’t take long for the military to recognize the potential of these flying machines.

Italy first used aircraft mainly for reconnaissance purposes during the Italian Turkish war. Between September 1911 and October 1912, aircraft were tested in active combat with the first mission on October 23, 1911.

Bulgaria followed suit during the First Balkan War from 1912 – 1913. However, the first war to use planes extensively would be the First World War.

The First World War

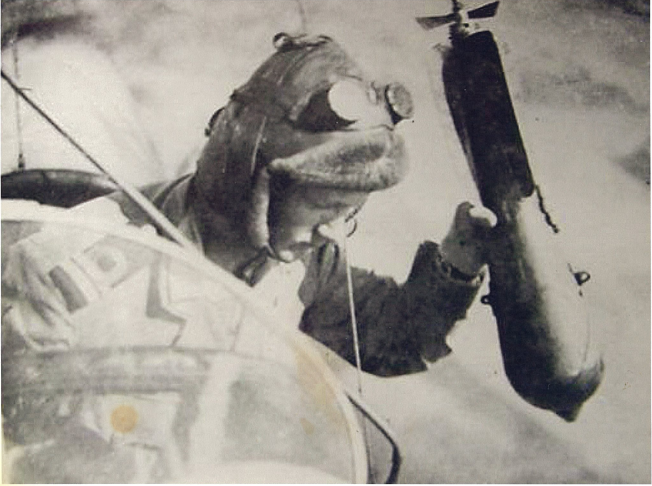

These planes were still flimsy contraptions, not particularly built for combat. At the beginning of World War I, soldiers dropped grenades manually and used hand held guns to shoot from the plane whilst trying to pilot the craft.

To this end aerial soldiers were fashioned as honorable knights in hand to hand combat. A few select soldiers gained fame and notoriety this way.

During WWI planes were made of wood, fabric and wire. ‘At the start of World War One, the aeroplane was barely a decade old. It had never been used in battle and was breathtakingly basic.’[9]

They were incredibly difficult and dangerous to handle, so much so, that the Flying Corps was nicknamed ‘the suicide club’.[10]

Shockingly, an RFC pilot’s average life was just 18 hours in the air and by 1917 they were losing 12 aircraft and 20 crew every day.

Over half of the pilot’s killed died in training, and ‘new pilots lasted on average just 11 days from arrival on the front, to death’.[11]

Lieutenant Cecil recalled:

‘You sat down to dinner faced by the empty chairs of men you had laughed with at lunch. The next day new men would laugh and joke from those chairs. And so it would go on.’[12]

The issue with weaponry was solved by Frenchman Roland Garros in late 1914. He was able to attach a fixed machine gun to the front of his plane and the rest of Europe followed suit. Germany developed their fighter plane with a synchronized machine gun and led the first aerial victory of World War I on July 1, 1915.

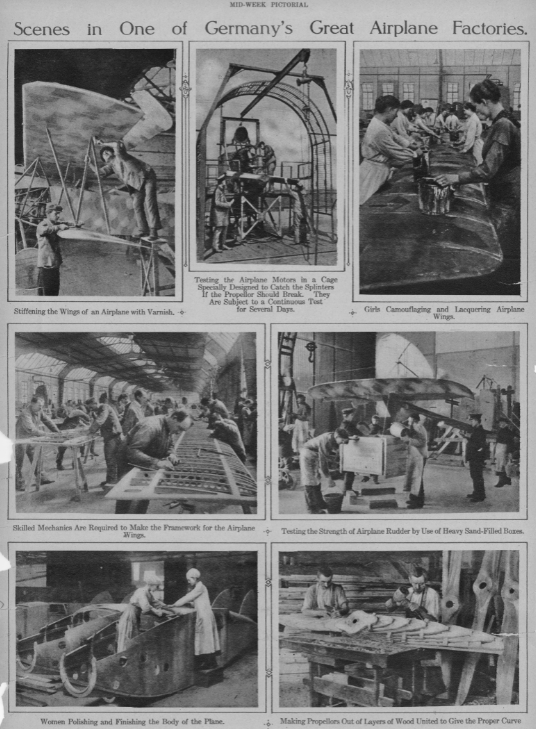

The forcing house of war had caused the aviation industry to grow at an alarming speed.

At the beginning of the war, Britain had 200 planes. At the end of the war, the military counted 33 thousand destroyed in action or scrapped and a further 22 thousand remaining.

The industry found itself without a customer, and government funding ended abruptly. Many fighter planes were sold off to private individuals who remodeled the planes for entertainment or leisure.

However, the war time years had been instrumental in the advancement of aviation. Planes were now capable of flying astonishing distances with great speed and control. The public were still fascinated by aircraft and aviators alike, and this fueled what is known as the Golden Age.

The Golden Age

Between the First and Second World War, private investors fueled barnstorming, cash incentive prizes, record breaking attempts and the gradual beginnings of commercial flight. This period of time bore witness to some of the greatest aviation feats of all time.

The household names of this time were Amelia Earhart, Charles Kingsford-Smith, Charles Lindbergh, Wiley Post, Harold Gatty, Howard Hughes, Clyde Edward Pangborn, Jimmie Mattern, Amy Johnson, Ruth Nichols, Roscoe Turner, Richard E. Byrd, Hubert Wilkins…. The list could go on indefinitely.

These extraordinary men and women broke countless records, smashed through barriers and convention and proved that the impossible was possible. They mapped and traversed the uncharted corners of the earth and connected mankind in a way hitherto unthinkable.

These men and women risked life and limb to prove the feasibility of commercial air travel so that we could connect people and cultures; so that we could broaden our horizons in every sense of the expression.

They were the heroes of aviation at a time when the government offered little financial support and the public, justifiably sick of war, were resolutely against the possibility of commercial flight.

We owe our Boeing, our American Airlines and British Airways to these aviators. They paved the way for our holidays, adventures and new found sense of connectivity to the wider world around us.

The technology around aircraft and navigation was greatly advanced at this time. Planes had developed from wood and canvas to ingeniously constructed, powerful monoplanes made from aluminum.

As pilots competed for cash prizes, the incentive for better, faster and sleeker aircrafts grew exponentially. Lindbergh’s 1927 Orteig Prize win for the first, solo, transatlantic crossing whipped the general public into an aviation frenzy.

Investors were suddenly throwing money at pilots in an attempt to capitalize upon the current trend. Suddenly, commercial flight seemed feasible, and the race was on to develop better and more reliable planes.

In the 1930’s Germany and Britain laid the foundations for the jet engine. They would pick up where they left off at the end of the Second World War.

The Second World War

Again, the forcing house of war saw an extraordinary increase in the pace of development and production.

Large scale bomber planes were launched, strategically dropping huge bomb loads in aerial raids. Throughout World War II the Lancaster bomber delivered 608,612 long tons of bombs in 156,000 sorties.

Bomber Command crews suffered a 44% death rate with 55,573 killed out of a total 125,000 aircrew. 8,403 were wounded in action, and 9,838 became prisoners of war.

The developments made after World War I offered the ability to attack small targets with greater precision. Air defense was far more coordinated with the development of radar technology. Air combat generally was far more strategic.

Commercial aviation grew rapidly after World War II as ex-military aircraft were regularly used to transport people and goods. The Lancaster was especially well designed to ferry cargo with its spacious bomber hold.

The Jet Age

The British de Havilland Comet was the first jet airliner to fly as commercial transport with BOAC.

This initial flight grew into a regular passenger service in 1952 before a series of technical failures came to light. Cabin pressure was not fully understood leading to serious failures in the plane’s windows and fuselage.

The jet age was ushered in by the USSR’s Aeroflot which commenced regular jet services with the Tupolev Tu-104 on September 15, 1956. Commercial air travel was actualized as the Boeing 707 and DC-8 offered a high level of comfort alongside safe and regular travel.

The sound barrier was broken by the rocket-powered Bell X-1 in October 1947.

Just a century after Cayley’s triplane glider, Chuck Yeager was able to surpass the speed of sound.

Further advances were made in in 1948 with the first ever Atlantic crossing made by a jet. In 1952 the first nonstop jet flight to Australia was realized.

The space race began in 1957 with the launch of Sputnik 1 by the Soviet Union. After the Cold War race to develop ever more efficient bomber and defense planes, the USSR had found a unique way to carry nuclear missiles.

The USSR had developed intercontinental ballistic missiles, and no aircraft could defend against them as the Cold War reached a dangerously hostile peak.

A mere 100 years after Ferdinand Von Zeppelin first flew in a balloon, Yuri Gagarin was orbiting the planet.

In 1961 he completed this circumnavigation of earth within 108 minutes. In a counter move, America launched a suborbital flight during the same year.

Canada sent a satellite into space in 1963, the third country to do so.

The space race ended with America’s successful 1969 moon landing. Again, war served as a catalyst for scientific advancements as Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong set foot on a small rock orbiting the planet below.

During the year of Apollo 11’s triumph, the Boeing 747 and the Aérospatiale-BAC Concorde supersonic passenger airliner took their first flights.

The Boeing 747 was a colossal ship capable of carrying up to 660 passengers. This was superseded by the Airbus A380, capable of carrying up to 853 passengers.

Supersonic passenger planes were unveiled in 1975 with the Tupolev Tu-144 Aeroflot. British Airways and Air France added supersonic services with the Concorde just 1 year later.

The English Channel was conquered in 1979 with the Gossamer Albatross. This flight would mark the first human powered aircraft to cross the channel as the 1980’s ushered in the digital age.

The Concorde G-BOAB hung up its wings in the year 2000 after having flown some 22,296 hours since its first flight in 1976.

Breaking speed and distance records were no longer of interest to aviation in the latter part of the 20th century. The primary concern of the digital age was the dissemination of the digital revolution.

The digital age would bear witness to some weird and wonderful innovations and achievements. Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager circumnavigated the world in the Rutan Voyager without refueling and without landing in 1986.

The balloon made a reappearance in 1999 with Bertrand Piccard’s flight around the earth.

The military became preoccupied with remotely controlled drones throughout the 21st century. The first Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) was tested in April 2001 with a nonstop flight from the United States of America to Australia in 23 hours and 23 minutes.

It is strange when considering the honorable knight styled pilots of WWI to comprehend the un-piloted UAV’s of the 21st century. The first entirely autonomous flight across the Atlantic took place in October 2003. Controlled only by computer and remote operator, the drone has fast become an accepted feature of modern warfare.

We continue to push further toward cleaner, more renewable energies, and in 2015 André Borschberg flew 4481 miles from Nagoya, Japan to Honolulu, Hawaii using only solar power. We strive to find new and inventive ways to reach the skies, to unburden ourselves from the shackles of this earth bound existence.

From the days of Icarus, ornithopter’s, lanterns and tower jumping, mass scale aviation has become an accepted part of everyday reality.

It is often easy to forget the courage, and the hubris, that has brought us to this point. Commercial space flight may be realized within our lifetime; no longer reserved for a select few.

Virgin Airways has begun a serious commercial space flight venture that could well achieve its aim. No longer content with traversing the skies, we look toward the next great frontier, outer space.

Bibliography

Anonymous, Transactions of the International Swedenborg Congress. (London Swedenborg Society, 1910).

Fairlie, Gerard; Cayley, Elizabeth, The life of a genius. (Hodder and Stoughton, 1965).

Fryer, Jane. ‘Bravery of British WWI ‘suicide club’ whose fighter pilots took on Germany and the Red Baron with only 15 hours’ training and lasted on average just 11 days,’ The Daily Mail, (DMG Media, June 10 2010), http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1283972/Bravery-British-WWI-suicide-club-fighter-pilots-took-Germany-Red-Baron-15-hours-training-lasted-average-just-11-days.html

Heinmuller, John P.V. ‘Chronology of Aviation,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945)

Lindbergh, Charles. Charles Lindbergh An American Aviator (linbergh.com), http://www.charleslindbergh.com/history/index.asp

Nicholson, William, A Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and The Arts, Vol. XXIV, (London: W. Stratford, 1809).

Footnotes

- Charles Lindbergh, Charles Lindbergh an American Aviator (linbergh.com), http://www.charleslindbergh.com/history/index.asp (date accessed: 21/09/16). ⏎

- Gerard Fairlie and Elizabeth Cayley, The life of a genius. (Hodder and Stoughton, 1965), pp. 163. ⏎

- John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘Chronology of Aviation,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. 232. ⏎

- Anonymous, Transactions of the International Swedenborg Congress. (London Swedenborg Society, 1910), pp. 45-46. ⏎

- William Nicholson, A Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and The Arts, Vol. XXIV, (London: W. Stratford, 1809), pp. 168. ⏎

- John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘Chronology of Aviation,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. 249. ⏎

- John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘Chronology of Aviation,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. 254. ⏎

- John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘Chronology of Aviation,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. 260. ⏎

- Jane Fryer, ‘Bravery of British WWI ‘suicide club’ whose fighter pilots took on Germany and the Red Baron with only 15 hours’ training and lasted on average just 11 days,’ The Daily Mail, (DMG Media, June 10 2010), http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1283972/Bravery-British-WWI-suicide-club-fighter-pilots-took-Germany-Red-Baron-15-hours-training-lasted-average-just-11-days.html (date accessed: 02/09/16). ⏎

- Jane Fryer, ‘Bravery of British WWI ‘suicide club’ whose fighter pilots took on Germany and the Red Baron with only 15 hours’ training and lasted on average just 11 days,’ The Daily Mail, (DMG Media, June 10 2010), http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1283972/Bravery-British-WWI-suicide-club-fighter-pilots-took-Germany-Red-Baron-15-hours-training-lasted-average-just-11-days.html (date accessed: 02/09/16). ⏎

- Jane Fryer, ‘Bravery of British WWI ‘suicide club’ whose fighter pilots took on Germany and the Red Baron with only 15 hours’ training and lasted on average just 11 days,’ The Daily Mail, (DMG Media, June 10 2010), http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1283972/Bravery-British-WWI-suicide-club-fighter-pilots-took-Germany-Red-Baron-15-hours-training-lasted-average-just-11-days.html (date accessed: 02/09/16). ⏎

- Jane Fryer, ‘Bravery of British WWI ‘suicide club’ whose fighter pilots took on Germany and the Red Baron with only 15 hours’ training and lasted on average just 11 days,’ The Daily Mail, (DMG Media, June 10 2010), http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1283972/Bravery-British-WWI-suicide-club-fighter-pilots-took-Germany-Red-Baron-15-hours-training-lasted-average-just-11-days.html (date accessed: 02/09/16). ⏎