The 13th child born to a family of pioneer settlers and sheep farmers, Sir Hubert Wilkins was to be anything but unlucky.

Born at Mount Bryan, South Australia, Wilkins was to go on to become an extraordinary polar explorer, ornithologist, soldier, photographer, pilot and geographer. As such he is an honored member of the Longines Honor Roll.

Beginning his eclectic career as an acclaimed aerial photographer Wilkins joined the Australian Flying Corps as a Second Lieutenant in 1917.

During WWI he was enlisted as an official war photographer often at the heart of active battle. Wilkins was awarded the Military Cross for his efforts in rescuing wounded soldiers during the Third Battle of Ypres and a bar added for commanding a group of lost American soldiers bereft of their officers.

Explore Under the Ice Shelf with the Nautilus

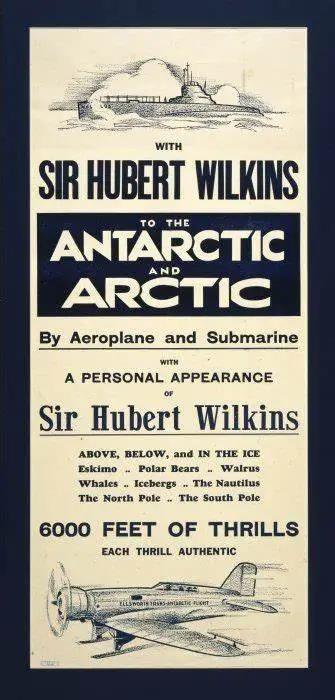

Surviving the war, Wilkins went on to make valuable discovers in aviation, ornithology and polar expedition. Above all, he was to discover a passion for the Polar Regions that would take him under the hardened ice shelf to explore a world below.

On June 4th 1931, Sir Hubert Wilkins and a meticulously selected crew of 18, left coastal waterways for the elusive and uncharted North Atlantic Sea.

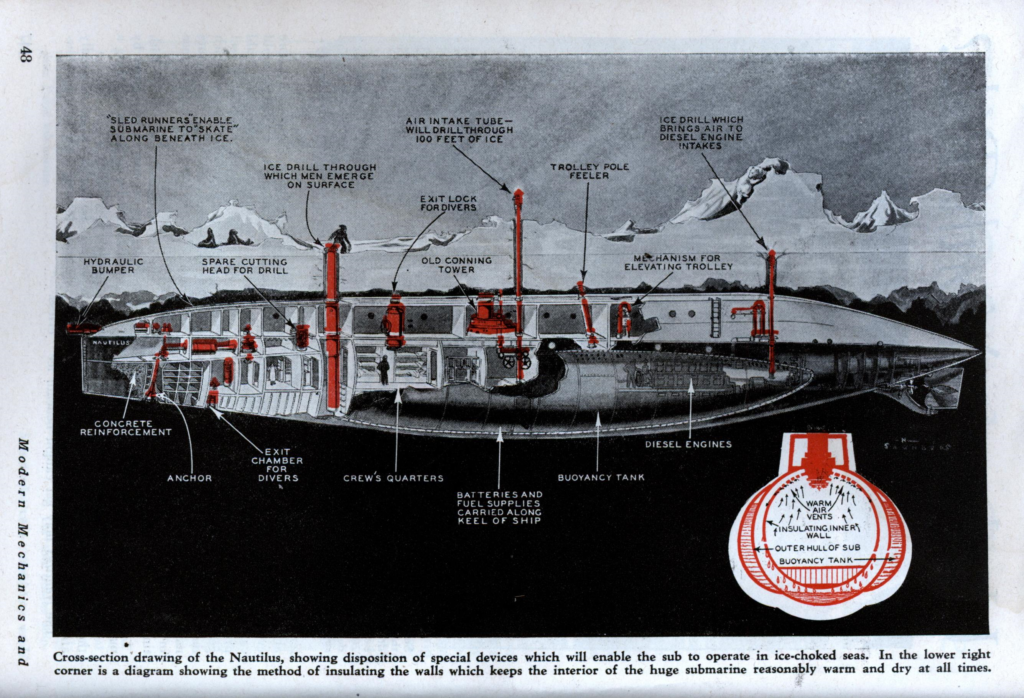

The Nautilus, named after Nemo’s infamous vessel in Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, was to be their submarine. At 175 feet in length and weighing in at 560 tons she was a gargantuan ship of massive proportions.

The Nautilus was custom built to drill through the ice pack overhead, for the purposes of ventilation, and capable of diving to a depth of 200 feet. The ship was able to support a crew of twenty men for five days should they encounter large expanses of ice with no open water.

As a pioneer of the natural sciences Wilkins had already made important discoveries as an ornithologist on the Southern Ocean and adjacent islands to great acclaim by the British Museum.

He went on to explore the utilization of drift ice in aircraft landing in March 1927. Wilkins and pilot Carl Ben Eielson landed safely on the icy platform measuring a water depth of 16,000 feet.

This would mark the first land-plane descent onto drift ice which would go on to aid and inform future polar expeditions.

With a love of Polar exploration fully realized in Wilkins he went on to make a trans-Arctic crossing from Point Barrow, Alaska, to Spitsbergen.

Leaving on the 15th of April 1928 and arriving some 20 hours later on April 16th, Wilkens was to be knighted for this feat, alongside prior achievements. Decorated with medals, titled and, more importantly, funded, Wilkens outlined the purposes for his daring polar submarine expedition:

In short, the expedition is for the purpose of gathering data in connection with a plan for comprehensive meteorology study, including the polar areas and with the hope that once polar meteorological stations are established it will be possible to forecast for several years in advance, the seasonal conditions, and to collect scientific data of academic and economic interest from an area hitherto unapproached by a scientific staff equipped with a complete scientific laboratory and facility for comfortably carrying out their investigations and provided with adequate means of sustenance and means of safe retreat. Millions of dollars are spent each year by various institutions in oceanographical and geophysical research. A submarine will provide means for similar investigations in an economic and safe manner, in areas as yet untouched by scientists.[1]

Characteristically macabre, as these expeditions often were, the quartermaster Willard Grimmer drowned before the crew even left the harbor.

Undeterred by this tragic misfortune the crew began their journey on June 4th 1931 on only to encounter a full engine breakdown; forcing Wilkens to send out an SOS signal for rescue by the USS Wyoming.

Not unlike Nemo’s fated adventures the expedition was daring in a somewhat foolhardy way. The ship itself was scheduled to be decommissioned, and yet an assuredly sturdy and seaworthy vessel.

As quoted in Popular Science Monthly, ‘Despite its age, it is said to be as staunch and safe as any recently constructed submarine.’ [2]

This assumption turned out to be rather unfounded after the ship had to be rescued only 10 days after departure.

After repairs the Nautilus set off once again on the 28th of June to pick up further crew members. Leaving Norway on August 23rd, only to find that the Nautilus was missing its diving planes, just 600 miles from the North Pole.

The absence of diving planes would make the submarine impossible to control while submerged. Determined to continue Wilkins crew managed to test the salinity of the water, the gravity surrounding the North Pole as well as taking core samples of the ice.

After receiving a wireless plea from financier Hearst, Wilkins was forced to reconsider the continuation of his already thwarted expedition. Hearst, concerned for his safety asked of Wilkins: “I most urgently beg of you to return promptly to safety and to defer any further adventure to a more favorable time, and with a better boat.”[3]

During the return journey Nautilus suffered irreparable damage during a fierce storm near Norway. In somewhat Nemo fashion, who plunges his own vessel into the abyss, Wilkins is given permission by the United States Navy to sink the vessel on November 20th, 1931.

Despite being unable to meet his intended objectives Wilkins mission was able to prove the capability of submarines below the polar ice cap. This mission has provided invaluable information to future polar expeditions wishing to explore the icy depths below the polar surface.

In June 1929 Longines writes that ‘Sir Hubert Wilkins has made priceless contributions to our knowledge of the vast Polar Regions during eight expeditions to the Arctic and Antarctic. He is the only man to explore beneath the polar ice by submarine.’ [4]

Upon his death in November 1958, the US Navy aboard the submarine USS Skate, scattered Wilkins ashes at the North Pole. The Navy confirmed that, “In a solemn memorial ceremony conducted by Skate shortly after surfacing, the ashes of Sir Hubert Wilkins were scattered at the North Pole in accordance with his last wishes.”[5]

Footnotes

- The Trans-Arctic Submarine Expedition Incorporated, ‘Purpose of Submarine Expedition,’ Under the North Pole: the Voyage of the Nautilus, (The Ohio State University Libraries), https://library.osu.edu/projects/under-the-north-pole/images/15-33-PURPOSE-OF-EXPEDITION-1.JPG (date accessed 15/08/16).

- Larry Brent, ‘Under Arctic Ice to the Pole!’ Popular Science Monthly, Vol. 114, No. 6 (Bonnier Corporation, June 1929), pp. 29.

- Time, ‘Science: Wilkins Through,’ Time, Vol. XVIII, No. 11, (Time Inc, September 14, 1931).

- Longines, ‘The Most Honored Watch in Exploration,’ Life, Vol. 10, No. 22, (Time Inc, 2nd June 1941), pp. 68.

- Anonymous, ‘Atomic Sub Drills Holes In Polar Ice’, Oakland Tribune, (17 March 1959), pp. 1.

Bibliography

Anonymous, ‘Atomic Sub Drills Holes In Polar Ice’, Oakland Tribune, (17 March 1959).

Brent, Larry. ‘Under Arctic Ice to the Pole!’ Popular Science Monthly, Vol. 114, No. 6 (Bonnier Corporation, June 1929).

Longines, ‘The Most Honored Watch in Exploration,’ Life, Vol. 10, No. 22, (Time Inc, 2nd June 1941).

Time, ‘Science: Wilkins Through,’ Time, Vol. XVIII, No. 11, (Time Inc, September 14, 1931).

The Trans-Arctic Submarine Expedition Incorporated, ‘Purpose of Submarine Expedition,’ Under the North Pole: the Voyage of the Nautilus, (The Ohio State University Libraries), https://library.osu.edu/projects/under-the-north-pole/images/15-33-PURPOSE-OF-EXPEDITION-1.JPG