Amy Johnson joins the likes of Amelia Earhart in her feats of aviation and her determination to break gendered stereotypes in a male dominated field. An extraordinary pilot, engineer and navigator, Johnson understood her craft intimately. Being dubbed ‘Queen of the Air’ by the British press, Johnson was a valued person of the Longines Honor Roll advertising campaign.

John P.V. Heinmuller writes that Johnson was ‘a serious student of flying, a steady, dependable and courageous aviatrix until the day of her death.’[1]

Amy Johnson with Longines Pilot watch.

A member of the Longines Honor Roll, Amy Johnson used Longines timepieces in many of her pioneering flights.

Original image from Longines.com/magazine/livre-des-exploits/chapter-07.

Johnson studied all aspects of flight including navigation, piloting and ground procedure. She became Britain’s first qualified female ground engineer and was the President of the Women’s Engineering Society from 1935-1937. Thus inspiring generations of women that proceeded her to pursue whichever profession they chose, despite any doubts or criticisms.

Born on July 1st 1903 in Hull, England, Johnson was to fall in love with aviation from an early age. She gained a pilot’s “A” Licence (No. 1979), on the 6th of July, 1929 at the London Aeroplane Club and went on to become the 1st female pilot to fly solo from England to Australia, an accomplishment earned over a laborious 19 days and 11,000 miles[4].

In 1930, at just 26 years of age, Johnson flew a de Havilland DH.60 Moth named Jason[2] from Croydon to Darwin, Northern Territory, on a journey that would span 11,000 miles. From May 5th to the 24th Johnson completed this gargantuan journey alone.

Amy Johnson with Jason in Australia 16, June 1930.

Image is public domain from wikimedia commons.

Upon her return, Johnson received awards; a title of ‘Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire award’, the Harmon Trophy and a personal congratulations, from the King Edward VIII of England. Having proven herself exemplary, Johnson was celebrated internationally as a courageous individual and a pilot of great talent.

A detailed account of her journey from London to Darwin is available on the British Heritage website here.

Uncontent with sitting idle, Johnson was back in the cockpit just one year later to break yet another world record. Flying 1,760 miles in just one day she alongside Jack Humphreys, a co-pilot, traveled from London to Moscow in July 1931. From Moscow they successfully crossed Siberia and flew on to Tokyo. In the G-AAZV de Havilland DH.80 Puss Moth, Jason II, a second record was set. This flight marked the quickest time flown from Britain to Japan in a remarkable 21 hours.

Johnson married the famous Scottish Pilot Jim Mollison on the 29th of July, 1932; together, they continued to trail-blaze the skies. While completing a number of joint flights, Johnson was resolutely her own woman and a talented pilot in her own right. She set another solo record which broke her husband’s in July 1932. Johnson flew from London to Cape Town in a Puss Moth named Desert Cloud in a flight that more than rivaled her male counterpart, beating Mollison by a full 10 hours in four days, six hours and 52 minutes.

In July 1933, Johnson and Mollison flew as a duo, in a G-ACCV de Havilland DH.84 Dragon I, named Seafarer, endeavoring to fly non-stop from South Wales to New York. Both wife and husband were hospitalized when Seafarer crashed just 150 miles from their final destination.

The poor bird was a wreck, completely destroyed in the crash while Mollison and Johnson were discharged from hospital in a matter of days. Upon questioning the crash ‘Mrs Mollison would only say that as the flight neared the end she and Captain Mollison had a disagreement, and he had refused to permit her to take over the control.

Possibly if he had let her relieve him at the time the accident would not have occurred.’[3] Despite the crash both Johnson and Mollison were celebrated with a ticker tape parade down Wall Street.

In 1934 they once again embarked upon a joint aviation venture. In G-ACSP, named Black Magic, a de Havilland DH.88 Comet they competed in the Britain to Australia MacRobertson Air Race. Unfortunately, engine trouble forced them down at Allahabad.

Johnson regained her London to Cape Town record from 1932 in her final long distance flight. Having been surpassed by Lieutenant Tommy Rose she flew in the G-ADZO, a Percival Gull Six, triumphantly taking back her title in 1938. In this same year she divorced Mollison, their aviation romance at an end.

Johnson was hard at work preparing for her first around the world flight when news of WWII hit the nation. She had devoted two years of her life meticulously planning every aspect of the forthcoming journey. She had become an expert aerial navigator through concentrated study and dedicated research. Putting all personal plans aside she immediately joined the war effort as an Air Transport Auxiliary with the RAF in 1940.

In 1941 she suffered a fatal crash, on a routine ferry command flight from Blackpool aerodrome in a twin-engine Airspeed Oxford, whilst headed for Kidlington Airbase, in Oxfordshire. The flight should have lasted 90 minutes, but she was not seen again until 4 hours later when; bailing from the plane on the river Thames in bad weather she drowned in the icy waters.

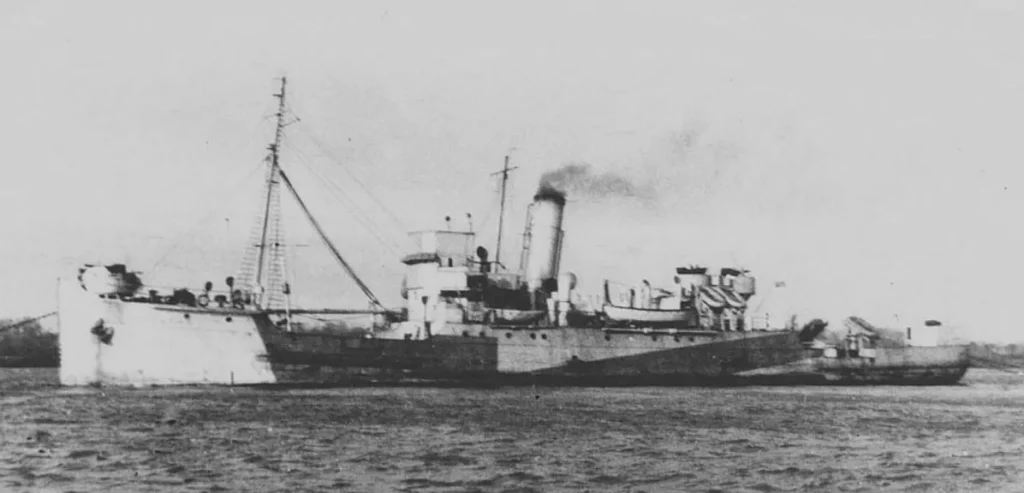

A barrage balloon tender, the HMS Haslemere was on station and immediately attempted to rescue the downed aviatrix.

Despite rescue attempt by the ships crew and captain, Lieutenant Commander Walter Fletcher, Amy lost her life. She was unable to grasp the lines that the crew threw to her in the frigid waters and the captain was unable to rescue her after diving into the Thames himself.

Lieutenant Commander Walter Fletcher himself, never regained consciousness after his attempt. It is speculated that the propellers of HMS Haslemere sucked her under. Her body was never found and the country was devastated to have lost one of its most beloved aviators.

Throughout her life she proved a remarkable and pioneering aviator, navigator and engineer. She inspired many women to follow in her footsteps in a male dominated field often full of detractors. She is a credit to her profession.

Amy V. Johnson is commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission on the Air Forces Memorial at Runnymede.

Bibliography

Anonymous, Biographies: Amy Johnson, History,(AETN UK, 2015), http://www.history.co.uk/biographies/amy-johnson

Heinmuller, John P.V. ‘XIII James Allan Mollison and Amy Johnson Mollison’, Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945).

Inside Out, Amy Johnson, BBC,(Yorkshire & Lincolnshire: BBC, 21st October 2002), http://www.bbc.co.uk/insideout/yorkslincs/series1/amy-johnson.shtml

Rosenblatt, Kalhan. ‘Death of flying pioneer Amy Johnson ‘was covered up after she was killed by ship sent to rescue her’’ Mail Online, (Daily Mail, 6th January 2016), http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3386622/Amy-Johnson-s-death-covered-killed-ship-sent-rescue-her.html

‘Amy Johnson’s 114th birthday: Five key facts about the UK’s pioneer female aviator’, (The Independent, 13th December 2021) https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/amy-johnson-114-anniversary-pioneer-female-aviator-first-woman-england-australia-flight-a7817956.html

Footnotes

[1] John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘XIII James Allan Mollison and Amy Johnson Mollison’, Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp.184.

[2] This aircraft resides in the Science Museum, London

[3] John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘XIII James Allan Mollison and Amy Johnson Mollison’, Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp.186.

[4] Chloe Farand, The Independent, ‘Amy Johnson’s 114th birthday’, paragraph 2