Alpha, Foxtrot, Charlie…

The Wright Brothers Kill Devil Hill Kitty Hawk adventures first started in a bicycle shed in 1903.Similarly, whilst Brazilian Santos-Dumont had flown with his famous Cartier watch in 1906, there was a limited need for its functionality as a timing instrument over his 220-metre journey and 21.5 seconds of flight.

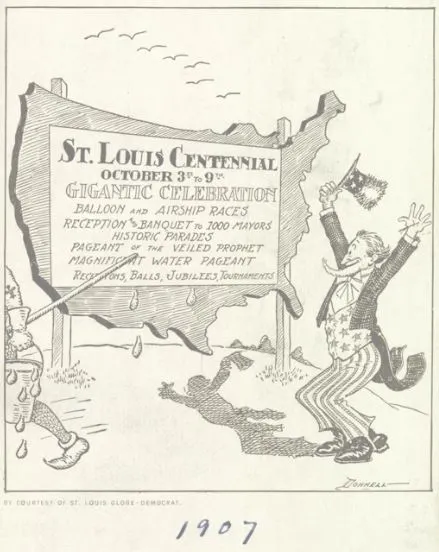

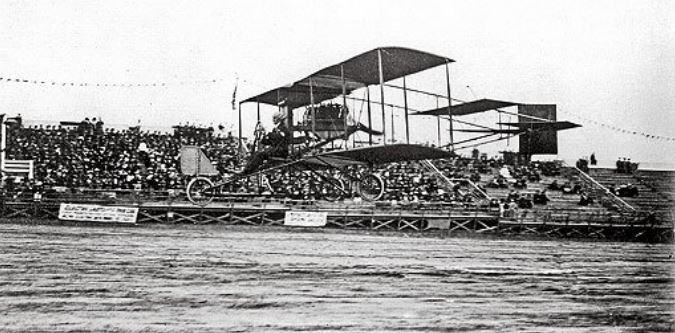

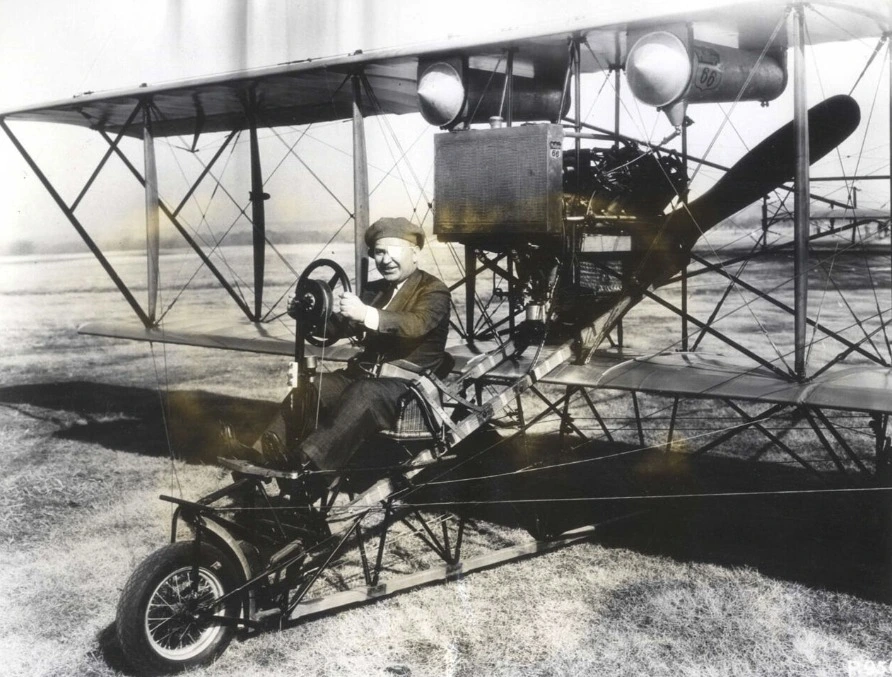

Planes, dirigibles, and balloons jockeyed for air supremacy, with the course of aviation history shaped forever during seventeen days in October 1910. Wellman’s dirigible America required a dramatic sea rescue after an unsuccessful Atlantic attempt, whilst Hawley and Post set a distance record in the Bennett International Balloon Cup, only to be lost in the wilds of Alaska.

The winner, the plane – after a nine-day aviation meet at Belmont Park, Long Island. Twenty-seven international pilots enthralled paying crowds who watched as speed, altitude and distance records were broken. It ended October 27, with the very first-ever race over a built-up area – around the Statue of Liberty, controversially won by the Frenchman, Henri Moisant.

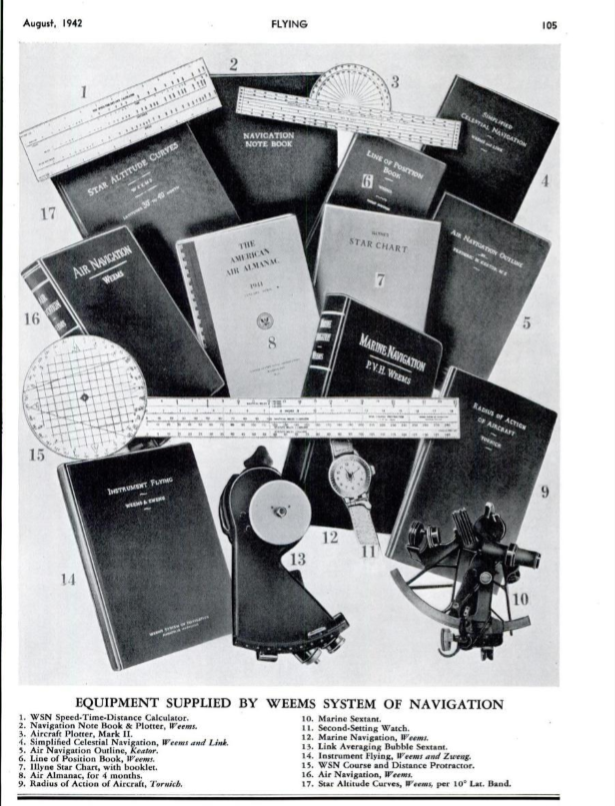

Pilots were soon dependent upon robust, accurate, and reliable timepieces, technical instruments, and their ability to use them. P.V.H Weems, the grandfather of the modern-day G.P.S system, whose air navigation techniques were used for three decades stated, “It is perhaps fortunate that timepieces were developed before radio, or else extremely accurate timepieces would probably never have been made”.[1]

He was robbed of an altitude record of approximately 50,000 ft in a propeller plane in 1934 because of faulty recording equipment and was the first person to study the effects of jetlag. His life was cut tragically short in Alaska at Barrow point after his plane crashed into the water from an altitude of 50ft just months after his altitude record attempt.

Even at this early stage, Weems noted, “the navigation timepiece have had generations of development and have attained a marvelous degree of perfection.”[2]

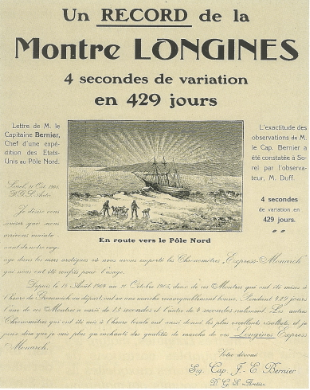

The 1904 reference concerning Captain Bernier, Canada’s greatest seaman, notes his Longines chronometers being just 4 seconds out over 429 days of adventure – an incredible feat and accuracy especially given the northern Polar extremes operating in.

The wristlet and wrist chronograph milestones were formed at the turn of the 20th century. They would soon find favour with aviators as popular functional timing instruments. Much of their DNA lies with a women’s 13 ligne pocket chronograph (échantillon pour montre de poche pour dame) first released at the Exposition Universelle de Paris of 1900 by Alfred Lugrin and another ladies’ 13’’’creation featuring an independent pusher at six o’clock patented in 1895 by Nicolet Fils & Cie.

The Paris expo creation was likely a collaboration with the watchmaker Jules-Fred Jeanneret whose collaborated with Alfred Lugrin as early as 1896. This same calibre found its way into some early 1910s mono-pusher wrist chronographs, before morphing and becoming the backbone of the famous Lemania 13CH and Omega 28.9 calibres.

Whilst size limitations may have initially limited aviation use of these pieces, A.Lugrin had also registered the Swiss patent, CH359, for a 19-ligne chronograph calibre in 1889. The watchmaker registered the famous Lemania trademark in 1906, however, it was not used until 1924, four years after his death.[3]

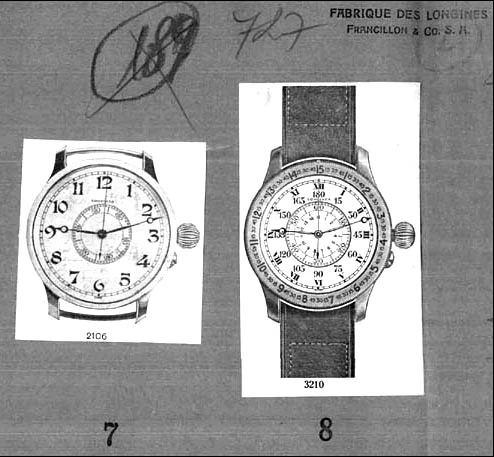

Size would not be an issue when Longines introduced its very first commercial wrist chronograph, the 19.73N, essentially using a thinner updated execution of their pocket watch calibre first born in 1897. The suffix “N” from the French word Nouveau, meaning new, was added as a movement notation.

Their very first example, in a 48mm case, with serial 2312118, and two other consecutive numbered pieces, were described along with those that followed as ‘wrist chronographs’ in their archive register. The three pieces made in May 1911 were invoiced to their Russian agent Schwob, in October of the same year.

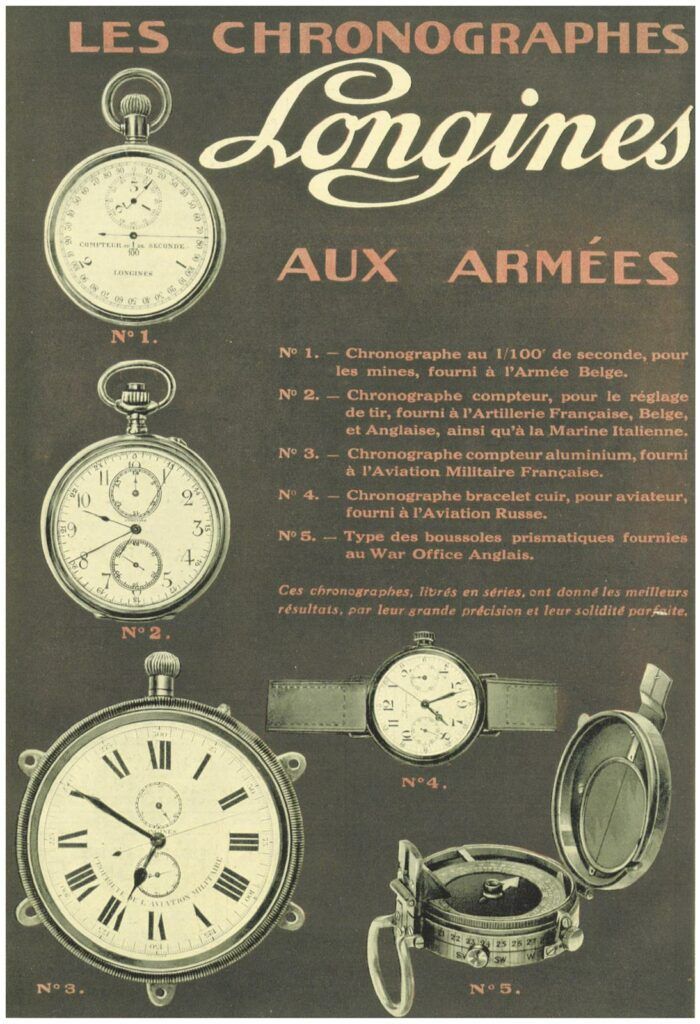

A further thirty pieces – in metal, silver and a few 14k gold cases were completed in 1911, and delivered to Russia between May and August 1912. It is highly likely some of these found their way to Russia’s early aviators. All thirty-three pieces predate the delivery of thirty repurposed Longines 13.67Z wrist chronostops delivered to Russia or America via their agents Schwob and Wittnauer in late 1912.

It was also the birth year of The Imperial Russian Air Service (IRAS), which by the start of WWI, had the largest air force in the world with 263 aircraft. Their nearest rival the French, had just 148.[4]

Other early oversized wrist chrono pieces by Henry Moser & Cie and Paul Buhre’s Faber type watches were also delivered to Russia in the leadup to WWI.

The year 1912 also saw P.V.H Weems graduate the U.S. Naval Academy and John Heinmuller, a young Longines watchmaker leave Switzerland to join Wittnauer, the American agent for Longines. Both would become two of aviation horology’s most influential key playmakers.

Weems would also play the greatest multi-decade role in the development and progression of air navigation and worked alongside, ‘Aero 1’[5], John Heinmuller, and other aviators in the creation of a range of specialist unique timepiece instruments.

The Swiss watchmaker, pilot, V.P, and later President of Wittnauer served for 30 years as the chief timer of the National Aeronautic Association and the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. He was directly responsible for timing and bringing official recognition to almost all of history’s seminal and record-breaking flights.

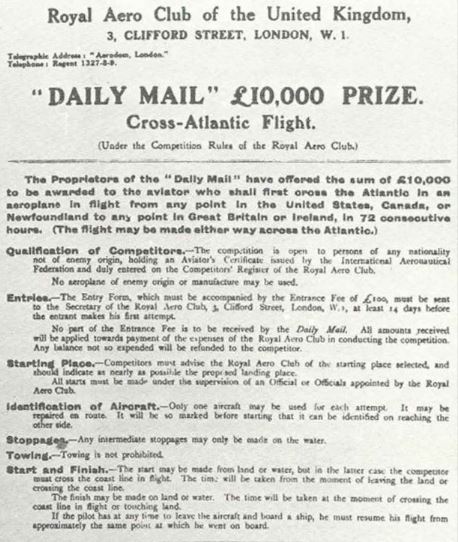

By 1913, growing aviation interest led to an incredible prize of 10,000 pounds offered by the owner of the London Daily Mail, Lord Northcliffe, for a trans-Atlantic crossing by plane. This offer would later be withdrawn as the world prepped for war.

It was the same year that Longines delivered the 13.33Z, their very first dedicated wrist chrono calibre. The hand-finished high-grade movement was very expensive to produce, and an examination of their archive records indicates the cost was approximately double the price of the famous 13ZN which arrived 23 years later.

It was used in watches worn by aviation greats Ruth Nichols, Amelia Earhart, Lindbergh, and America’s pole-conquering hero Admiral Byrd among others. The La Chaux-du-fonds maker Nathan Weil also featured 1913 ads about the availability of a 16’’’ early wrist chronograph collaboration with Marcel Depraz. There is a high likelihood that these pieces were supplied a number of years earlier.

Preparations for the Great War also led to the development of aircraft clocks. In England’s case, separate orders were made by both the War Office and Admiralty leading to the delivery of a type of cockpit clock based around a pocket watch.

Essentially these 8-day Swiss nickel or plated steel pocket watches, made by Octava, Eterna, Billodes (Zenith), Douard, and Nicole, Nielsen & Co Ltd et al were mounted on the plane’s bulkhead with a protruding pendant.

The pieces featured military markings, including nomenclature details on the dial, and were supplied with or without lume.

Similarly, in the States, Heinmuller, became the key driving force supplying cockpit instruments to the burgeoning U.S. Army Air Corps made by either Longines or Wittnauer.

In 1914, Gallet made their first delivery of an all-silver wrist chronograph to the British Royal Air Force with a 38mm silver cased pusher in-crown piece using a 15 ligne Valjoux base calibre movement.

As hostilities increased, the nation’s war needs dramatically expanded, and aircraft pocket watch-type clocks soon morphed into dedicated plane calottes. One of the most beautiful is a magnificent Longines white dial example, using calibre 19.75, first supplied in 1915 to the French Airforce. The text ‘Propriété de l’aviation militaire’ (Ownership of military aviation) appears above the six o’clock position. With the war’s arrival, advertisements for these pieces also appeared in the French magazine title, L’Illustration.

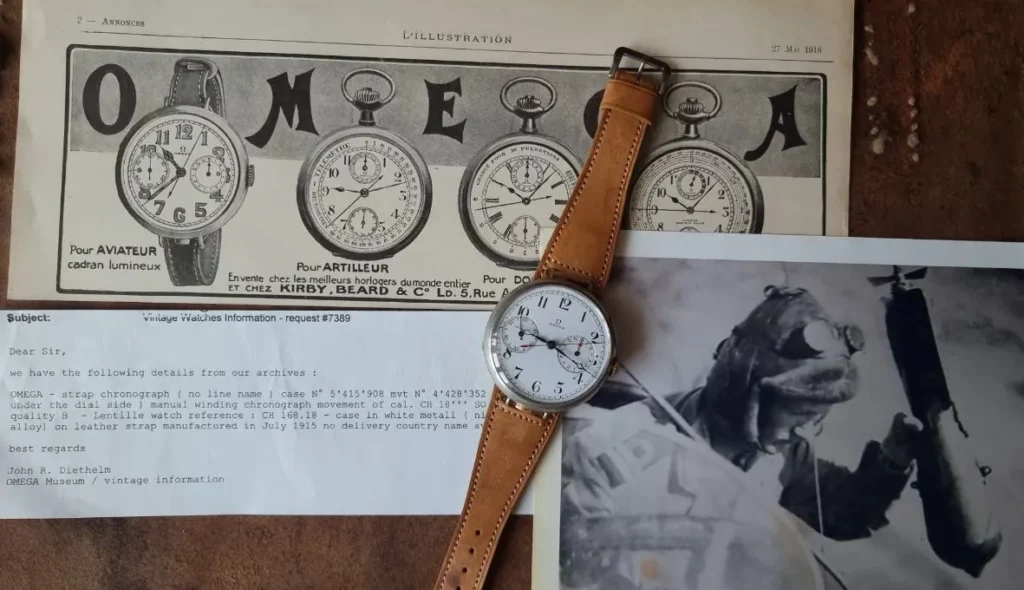

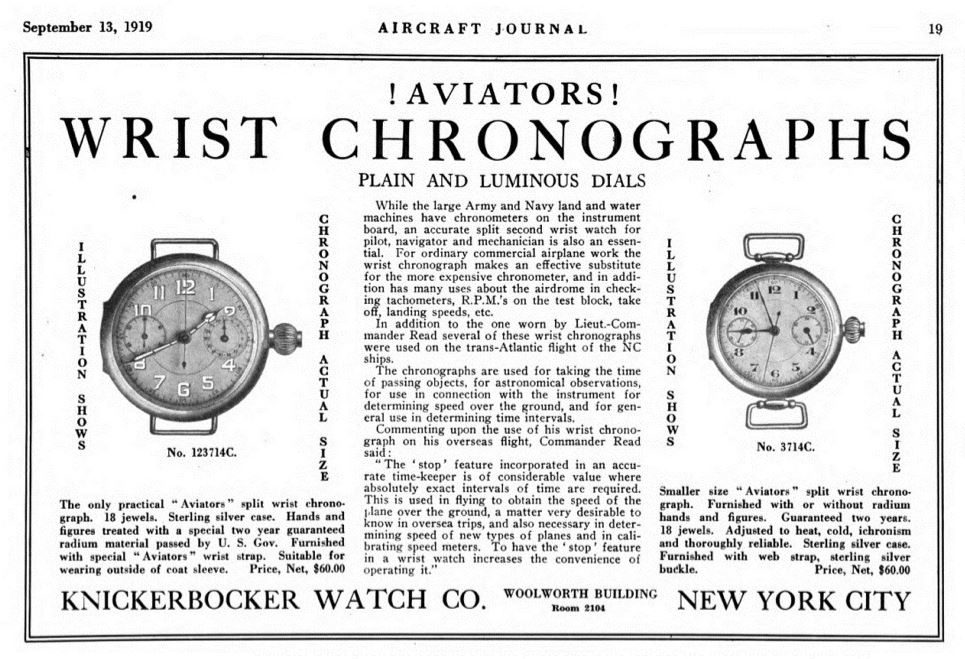

By 1915, wrist chronographs appeared from other makers including Omega who supplied the ref CH 168.18 in July and reference 568.18 in September. Both oversized, the 44mm and 46mm creations used an 18 ligne pocket watch calibre and sported an oval pusher at six.

Supposedly, the British intelligence officer, Thomas Edward Lawrence, the famed ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ had a ref 568.18 Omega wrist chronograph reference with a radium dial featured in advertisements from this time. However, whilst this watch now resides in the Omega museum, research points to “his” watch having numbers that indicate it was born from two watches including a pocket watch. In recent years, Omega remade 18 limited edition 18k white gold examples using a vintage 100-year-old reworked 18’’’ calibre.

Omega pipped the introduction of Breitling’s 41mm Montbrillant 16’’ wrist chrono model, which laid claim to being the very first chronograph with an independent pusher at two. Its challenger, Gallet’s so-called Valjoux 22GHT, used a Reymond Freres movement and arrived at a similar time. The watch was housed in a larger 38.5mm case and also supplied to the British military forces.

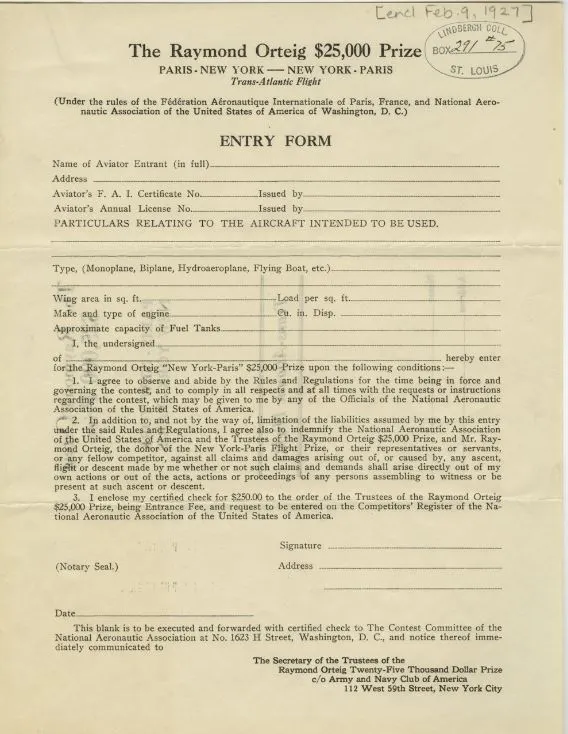

The trans-Atlantic plane challenges first offered by the Daily Mail in 1913, and six years later by Raymond Orteig, would both play crucial multi-decade roles in air navigation and horological history.

The former had been rescinded during the war and when reinstated in 1918, rule changes precluded mid–ocean stoppages. The offer read, “the aviator who shall first cross the Atlantic in an aeroplane in flight from any point in the United States of America, Canada or Newfoundland to any point in Great Britain or Ireland in 72 continuous hours“.[6]

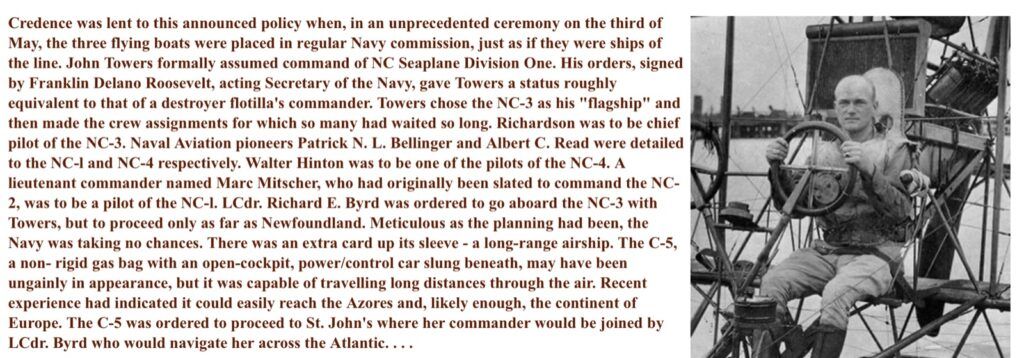

America planned for the US Navy’s (N) Curtiss (C) seaplanes to be first across. Following meticulous planning, they formally commissioned the NC Seaplane Division on May 3 1919, just two days after the first flight of the NC-4. Although technically excluded from claiming the prize because of the timeframes involved, a successful Atlantic crossing was about national pride.

Three Nancies, the nickname given to these US navy seaplanes set off, attempting to make the world’s very first trans-Atlantic plane crossing. The five-man crew of the NC-4 was the only successful Nancy flying from New York State to Lisbon after a six-leg, 19-day voyage including transit, maintenance, and rest stops.

The citation given by Acting Secretary of the Navy, Franklin D. Roosevelt to Lt. Stone, one of the pilots on 23 August, 1919 for his part of the NC-4’s success read,

“I wish to heartily commend you for your work as pilot of the Seaplane NC-4 during the recent Trans-Atlantic flight expedition. The energy, efficiency, and courage shown by you contributed to the accomplishment of the first Trans-Atlantic flight, which feat has brought honor to the American Navy and the entire American Nation“. [7]

The citation given by Acting Secretary of the Navy, Franklin D. Roosevelt to Lt. Stone

The Americans spared no expense with their Seaplane Division for the 3905 nautical mile crossing attempts of May 1919. They used more than 50 US Navy vessels[8] stationed enroute to assist with air navigation via radio communication and pilotage.

The shaping of air navigation and the history that followed from this event can be explained by the following passage. “Twenty-five hundred feet below on board a station tracking ship, a young navigator, Lt. Cdr. Philip Van Horn Weems of the U.S. Navy, gazed up and thought there must be a safer and simpler way than using a small armada of ships as beacons for the flight. Lt. Cdr. Weems, a brilliant, inventive, and determined young man knew as he tracked that first flight that navigation was his destiny”.[9]

Just like Harrison’s conquest calculating longitude on the sea 200 years earlier, P.V.H Weems would soon play an inventive, integral, and instrumental part in overcoming the new challenges of air navigation. Weems angered traditional-thinking superiors by pursuing new methods of air navigation. The techniques, skills, and equipment would last for the better part of three decades.

His 1919 experiences would later lead to his Weems System of Navigation and multiple books on Air Navigation. It also led to the development of the two most famous pilot watches in history.

His famous Second setting watch, enabled the exact second to be set, relative to the hour and minute hands. The inner chapter ring disc could be rotated in either direction to gain an additional accuracy of +/- 30 seconds by using a radio signal or other known exact timepiece and Lindbergh’s improved Hour-angle version enabled and expedited the calculation of longitude.

The US Nancy honor and prestige was short-lived and overshadowed by a non-stop Newfoundland to Ireland crossing just 19 days later by John Alcock and Arthur Brown on June 15, 1919.

Sadly, the British aviator’s timepieces remain unknown and at large to this day. However, their 1890-mile flight in a modified Vickers Vimy bomber took 15 hours 57 minutes and enabled them to claim the 10,000 pound Daily Mail prize.

The year 1919 saw Longines become the official supplier of navigational instruments of the International Aeronautic Association. French hotelier Raymond Orteig also offered an incredible prize of 25,000 USD for a non-stop aviation crossing of the Atlantic, between New York and Paris, in either direction.

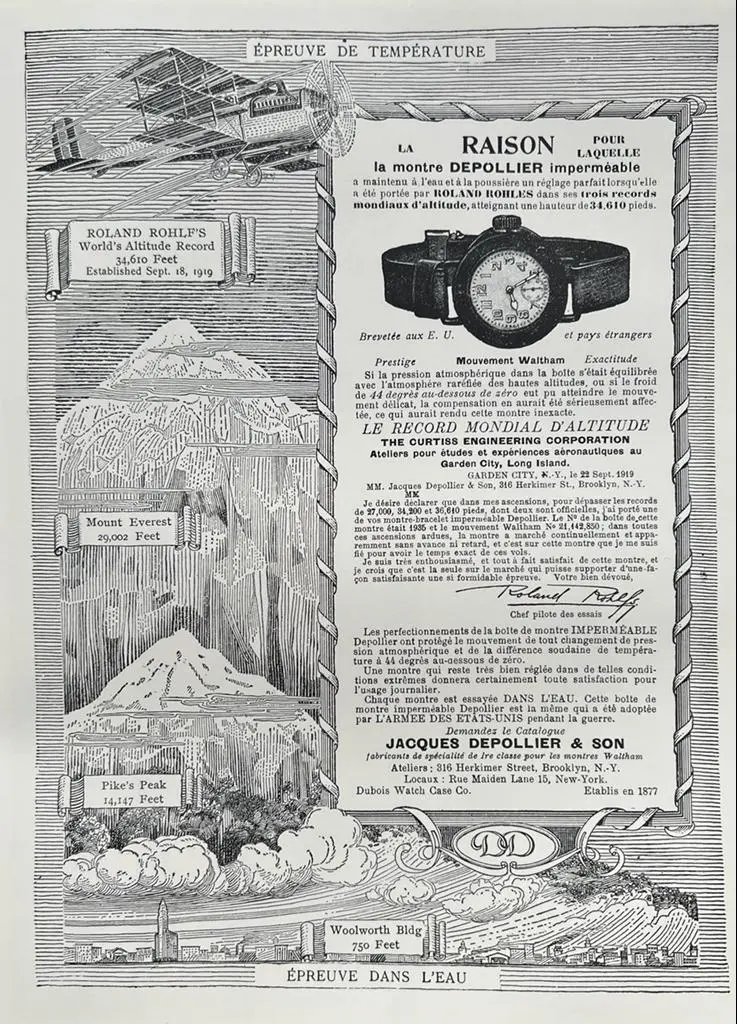

On September 18th, 1919, Roland Rohlf an American test pilot for Curtiss planes set a new Fédération Aéronautique Internationale altitude record of 34610 feet. He was sporting a Waltham sub-second wristwatch with an impermeable case retailed by Jacques Depollier & Son for his six-mile-high adventure. The watchmaker and model likely pipped Rolex to the crown of making the world’s first waterproof watch.

The commercial and aviation exploration age had its own set of challenges. Almost no one could see the civil age of aviation that lay a few short years ahead. However, the nation’s airmen and women left over from the Great War sought to prove aviation’s potential and address aircraft vulnerabilities and expenses in international competitions chasing speed, distance, duration, and altitude records. Aviation and exploration exploits soon became a bright spot in the mid-twenties.

Larger, more efficient, reliable performance engines, the benefits of weight reduction from aluminum led to dramatically improved opportunities in the aviation industry. Entrepreneurs and governments were starting to see the transportation and military potential opening access to funding – although, at times, this was challenging to acquire.

The horology industry was also trying to escape the ravages of war, where dramatic production cost increases and industrial disputes led to complex business challenges. A new two-pusher, aviation-type chronograph that featured a pusher in the crown arrived from Breitling in 1923. This would later lead to the development of a chrono featuring two independent pushers – a prize claimed by the Longines flyback 13.33Z, a few short years later.

Aviation’s navigation and horology needs were challenged by the increasing speed of the plane, duration, nighttime flying, and the difficulty of determining one’s position over large expanses of sea, heavy cloud cover, and unchartered territory. Initially, just two basic methods of early navigation existed. The first – ‘pilotage’, where known landmarks, rivers, mountains, and maps were used to assist at lower altitudes. The other ‘dead reckoning’, included taking the last definitely known position, and carrying forward with the last known speed, drift, course, and use of a compass.

Radio navigation was added to the mix – greater signal accuracy allowed perfect and easier time synchronization worldwide. This expanded significantly in February 1924, when the British Astronomer Sir Frank Dyson developed the so-called Greenwich Time Signal (GTS). This would become known as the famous BBC “pips”, a series of six short beeps heard every hour, on the hour – providing an accurate start for the time signal. The pips were broadcast from BBC radio stations and synchronized using two mechanical Royal Observatory clocks in Greenwich.

Navigation techniques and improvements dramatically advanced commercial, recreational, and military aviation pursuits alongside the evolution and progression of the transportation age.

The next chapter post-1925 would see the need for specialist purpose-built navigation timepieces during aviation’s golden age. One of the rarest reminders of this incredible timeframe is a Waltham Second-setting watch of Lindbergh’s with crude hand-marked unit of arc notations that likely made its way to him post-1927 would soon provide inspiration for a range of specialist Longines creations.

Any pre-1925 pilot watch is bordering on, or already a centurion, and all pieces are exceptionally rare. The dangers of the early aviation industry cannot be overstated. Further, any military application led to extinction-type outcomes for the pilot, plane, and their watch, especially during a military engagement, and has also been compounded by other unforeseen events post being issued.

Almost all examples have enamel dials and all pre-1925 wrist chronographs are exceptionally rare and highly coveted. It requires little imagination to grasp why there are so few survivors. Almost all examples elude even the most hawk-eyed and nimble of long-time collectors.

Specialist aircraft calottes and wrist chronographs from this incredible timeframe took to the skies, and became reliable and trusted timing companions of those who risked all. These first-class, high-altitude, rarified air horology survivors will still be here in another hundred years or more. They will help you tick longer, fly higher and further than you’ve ever been before.

A very special thanks to Khalid for his wonderful insights and input IG(@vintagepointbarre)

Footnotes

- Air Navigation Weems 1931 first edition p399

- Air Navigation Weems 1931 first edition p360

- Special thanks to Khalid (IG@vintagepointbarre for all of his help).

- History of light aviation of the French Army 1794–2008, Lavauzelle, Collection of History, Memory and Patrimony, Général André Martini, 2005, Paris, pages 36,42, ISBN 2-7025-1277-1

- Wittnauer – A History of the Man & his Legacy – Parillo Communications Ltd p44

- Flight magazine. 21 November 1918. p. 1316

- 1919: NC-4 Transatlantic Flight – Coast Guard Aviation History (cgaviationhistory.org)

- The U.S. Navy’s Curtiss NC-4: First Across the Atlantic | HistoryNet

- Weems & Plath, Weems & Plath Thermometers, Weems & Plath Hygrometers, Weems & Plath Barometers, Weems & Plath Weather Stations (weathershack.com)