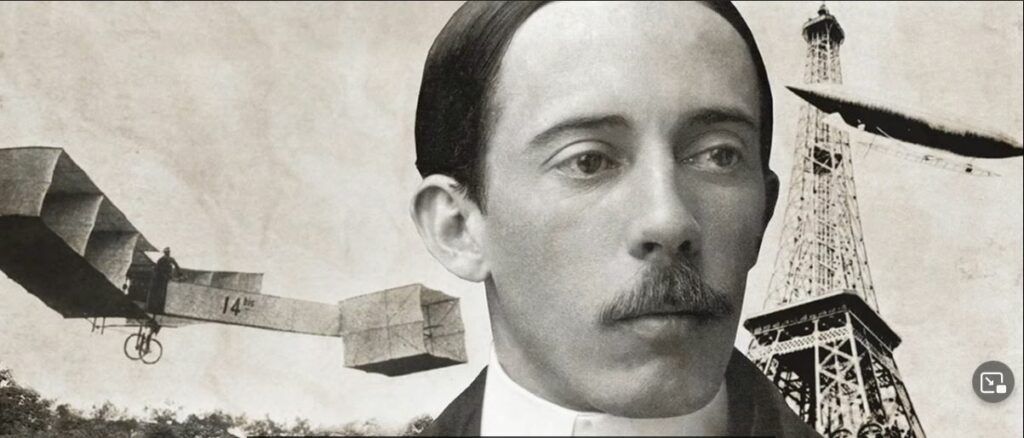

Whilst Santos-Dumont had flown with his famous Cartier watch in 1906, there was a limited need for its functionality as a timing instrument over his 220-meter journey and 21.5 seconds of flight. However, as planes became faster and more reliable over greater distances, an accurate timepiece for the air navigation age was not just required, it was a necessity.

Planes, dirigibles, and balloons jockeyed for air supremacy, with the course of aviation history shaped forever during seventeen days in October 1910. Wellman’s dirigible America required a dramatic sea rescue after an unsuccessful Atlantic attempt, whilst Hawley and Post set a distance record in the Bennett International Balloon Cup, only to be lost in the wilds of Alaska.

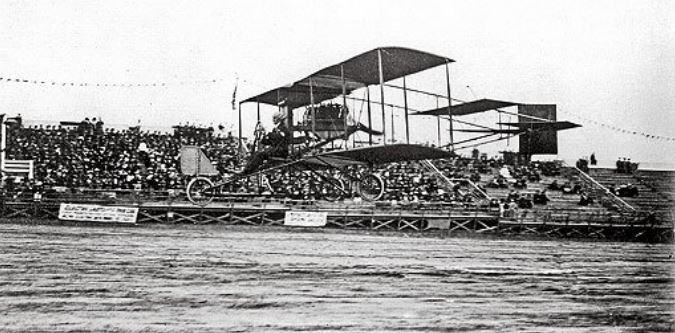

The winner, the plane – after a nine-day aviation meet at Belmont Park, Long Island. Twenty-seven international pilots enthralled paying crowds who watched as speed, altitude and distance records were broken. It ended October 27, with the very first ever race over a built-up area – around the Statue of Liberty, controversially won by the Frenchman, Henri Moisant.

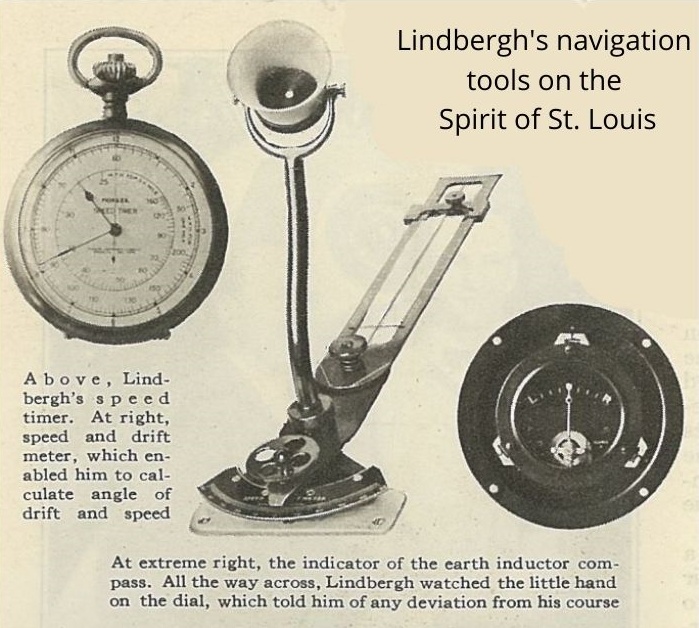

The speed of the plane brought complex new navigational challenges. When traveling at 200 miles an hour, a kilometer is covered in just eleven seconds. Countries (including island fuel stops) quickly disappeared – bringing oceans, uncharted territory, and a risk to life if navigational calculations were wrong.

Just as Harrison’s quest for the mastery of longitude, sea navigation and his development of marine chronometers almost 200 years earlier, air navigation came to the fore.

Pilot’s lives depended on the reliability and accuracy of aviation timepieces and technical instruments as well as their ability to use them. Weems stated, “It is perhaps fortunate that timepieces were developed before radio, or else extremely accurate timepieces would probably never have been made”. [1]

Radio signal accuracy allowed perfect and easier time synchronization worldwide. This expanded significantly in February 1924, when the British Astronomer Sir Frank Dyson developed the famous BBC “pips” using two mechanical Royal Observatory clocks which became known as the Greenwich time signal.

The grandfather of today’s GPS system and the backbone of this air navigation age was Lieutenant Commander Philip Van Horn Weems (1889-1979). He was a pilot and master navigator who published a number of papers and books.

His Weems System of Navigation training courses were adopted by the US Navy, commercial airlines, Byrd, and Lindbergh after his Atlantic success.

Weems also devoted his lifetime toward improving instrumentation and navigation techniques for long distance flying.

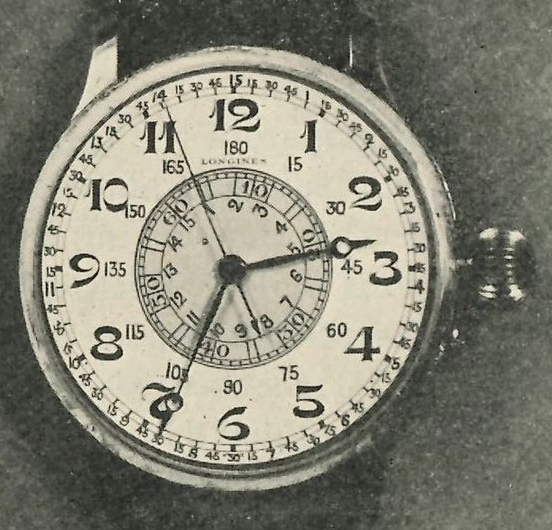

This remarkable time served as backdrop for the creation of the two most important aviator’s timepieces ever made: the Longines Weems ‘Second-setting’ watch which allowed for improved time synchronization, and Lindbergh’s ‘Hour-angle’ model simplifying longitudinal calculations. With just a pair of hands and a dial, a watch could be used to calculate gasoline consumption, ground speed, load-lifting capacity, tell time and navigate using celestial observations.

A Longines Weems & the improved Lindbergh Hour-angle watch

The Weems second setting watch was improved by Lindbergh who took up avigation training with Weems in 1928 after getting lost enroute over the Carribean. A few short years later in October 1931 the improved Hour-angle watch made famous by Lindbergh allowed easier avigational calculations.

Rear Admiral Moffett, who was the chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics for the US Navy Department stated “The suggestion… as to a moveable second-hand dial is considered to be a very valuable one, greatly facilitating the process of keeping a clock set to the exact time.” [2]

Developed specifically for aviators with the Aircraft squadron’s battle fleet, it was officially designated as a “second setting navigation watch”[3] by the U.S Naval Observatory. It was later distributed by them to the US Naval air stations and fleet along with filling private and government orders for the next twenty odd years.

Today Weems’s actual Longines ‘Aerochronometer’ as described in his 1931 Air Navigation book watch rests in the Smithsonian, absent its crown and is one of history’s most important pilot watches.

Adopted by Weems, the name and part of its function lies with the man Lindbergh described as the “Prince of Navigators,”[4] Harold Gatty. He used it to describe a timing device which offset aircraft speed inaccuracies when making navigational observations.

Weems’s ideas were first brought to life using modified Waltham Vanguard pocket watches prior to the arrival of the improved Longines wrist version.

Whilst little is known of the watch worn on his successful Atlantic crossing in May 1927, Lindbergh owned a modified Waltham Vanguard pocket watch and a hybrid Longines Weems hour-angle, pictured in the first issue of Weems Air Navigation book published in 1931. Six months later, the first turning bezel watch was born, a hybrid Weems/Lindbergh Hour-angle prototype.

The watch was a hand edited hybrid Weems of sorts, with a dial featuring notations for units of the arc and this was the precursor to the most famous drawing and watch in Longines history.

Weems wrote comments during publication that Longines were working on a graduated dial in arc, not time, along with “… a moveable bezel working on the same principle as the second-setting feature of the Aero Chronometer is fitted to the watch. The markings on the bezel are in degrees and minutes of arc only.” [5]

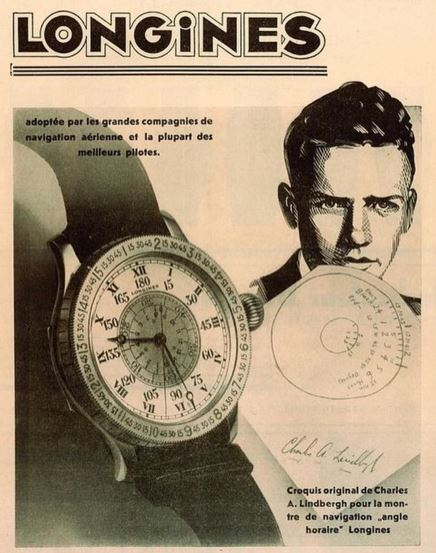

Heinmuller met Lindbergh shortly after he broke the US transcontinental speed record from Los Angeles to New York on April 20, 1930. In a letter to his wife, he wrote “…I was privileged to work out details of his latest instruments with him as the enclosed design from him will show. Keep it for our records. His latest ideas incorporate a second setting device for Greenwich Time, taken from the radio. The device… permits laying down of a position in less than three minutes. Navy experts at Annapolis say it is the most outstanding aviation improvement in many years”. [6]

The hybrid watch, Weems, Heinmuller and the Longines technical team in St Imier were the formative pieces bringing life to Lindbergh’s famous 1930 drawings and delivery of Hour-angle prototypes in December 1930.

Lindbergh commented he was examining the watch in a letter to Heinmuller in February 1931 and commented on its perfect timing in July. A patent request was filed for history’s most famous pilot watch, the Hour-angle, in October 1931. This watch, along with Lindbergh’s Waltham ‘Weems’ and a special Longines aircraft calotte have survived to this day and are some of history’s most important watches.

The Hour-angle could calculate longitude, the hands giving you time in hours, minutes, and seconds, whilst the bezel and the inner chapter allowed you to establish your position in degrees, and units of the arc based on the bezel graduations and inner chapter markings.

Air navigation was a critical component to the progress, safety and the development of aviation as a whole. Accurate, reliable timing instruments were a critical part of establishing one’s position. This golden age of the aeroplane promised a shrinking world, bringing with it the challenges of duration and distance flights.

The rigors of flying at night over unchartered and unknown territory, with ever changing weather, and voyages over the sea created their own set of unique complex challenges.

In early aviation, two basic methods of early navigation existed. The first – ‘pilotage’, where known landmarks, rivers, mountains, and maps were used to assist at lower altitudes. The other, ‘dead reckoning’, included taking the last definitely known position and carrying forward with the last known speed, drift, course, and use of a compass.

To this, both radio and celestial navigation were added.

Heralding from the latin word ‘sidus’ meaning star, sidereal time essentially meant Star time, with a day measured according to the so called ‘fixed stars’, not set to the sun but relative to the other stars.

Sidereal time watches were regulated fast by 3min 56.6 seconds, with any adjustment noted in the archive for both Lindbergh and Weems models. Watches adjusted for sidereal time were most often used as a pair, for special missions with the other watch adjusted to civil time.

Wiley Post and Harold Gatty used a pair or Weems adjusted in this manner, creating history with their record breaking round the world flight in 8 days, 15 hours, and 51 minutes in June 1931. Longines archives note their first use of a star on the dial to indicate sidereal time on October 25, 1932, and the Longines Weems was the very first sidereal time wristwatch.

United States military celestial training schools run by Weems, Gatty et al in locations across America, such as Maryland and San Diego also taught large numbers of female navigators for the US military.

These navigators existed in any of the following American military units WAVEs, WASPs and WACs who were often working in Ferry command. Amy Johnson, the first lady to fly from England to Australia noted that Weems was the best teacher in the world for celestial navigation on long flights.

Longines played an incredible role delivering functional purpose-built aviation timepieces that helped shape safety and critical navigational calculations in the air age. They remained the dominant and pre-eminent player from the birth of the perhaps the very first wrist 19.73N chronographs delivered in 1911 likely destined for Russian aviation, right through to a purpose-built model for Swiss Air in the 1950’s.

The second setting watch allowed easy time synchronization with radio signals. It was accurate, robust and highly functional. Lindbergh’s improved hour- angle watch of 1931, allowed for the easier calculation of longitude.

Both models had a large 47mm case, enabling them to be worn over a flight suit, whilst the large onion crown allowed operation with gloves. Both the Weems second-setting watch and Lindbergh’s own hour angle watch could be regulated for sidereal time and an adjustment for same would be noted in the archives.

Dramatic improvements in radio communication, radar and beacon technology radically changed aviation navigation just a few short years later.

Radio Navigation: “Flying the Beam” | Time and Navigation (si.edu)

The famous slide rule features of Breitling’s first Chronomat ref 769 of 1946 would soon follow, whilst the famous Navitimer, in the early 1950’s.

[1] Air Navigation Weems 1931 first edition p399

[2] Air Navigation Weems 1931 first edition p400

[3] Air Navigation Weems 1931 first edition p400

[4] Terry Gwynn-Jones, ‘Harold Gatty: Aerial Navigation Expert,’ Aviation History Magazine, (World History Group, September 2001), http://www.historynet.com/harold-gatty-aerial-navigation-expert.htm (date accessed: 19/08/16).

[5] Air Navigation Weems 1931 first edition p399

[6] Man’s Fight to Fly John Heinmuller p75