The “King of Timepieces in the East,” [1]was Kintaro Hattori, who began importing Swiss and American watches directly into Japan in 1886 through Hattori & Co, becoming one of the largest watch sellers in Tokyo during the Meiji era[2]. He turned his hand to manufacturing after opening the Seikosha factory in 1892, making their first watch, a Time Keeper branded pocket watch three years later.

Following business trips abroad he employed technological hybridization,[3] borrowing the best from both the Swiss and Germans in terms of precision and innovation, combined with the American mass production model. By 1910, his brand, Seikosha, was the only one still making pocket watches in Japan, albeit at a loss.

Hattori’s watch making was subsidized by the sale of imported Swiss and American made watches and clocks. He did not break even in watchmaking until 1913[4], the same year that Seikosha made their very first wristwatch for the Japanese market, the enamel dial ‘Laurel’. Hattori was an agent for Longines as early as 1911, importing thousands of their and other Swiss made movements.

Their success was in part attained from Japanese customs protectionism, which supported a substitution industry. However, they also relied upon the profits from Swiss watch sales and Hattori’s technological know-how, development and progression, which advanced significantly after studying the construction of these imports.

Hattori’s product quality was equivalent to, or at times, even better than Swiss watches, according to an October 1933 internal report by the Allgemeine Schweizerische Uhrenindustrie AG(ASUAG), the holding company controlling production of Swiss watch movements. [5] This was confirmed by expert tests done by the ASUAG in Le Locle on fourteen watches, including nine made by Hattori.

The Swiss embassy in Tokyo secured samples for testing in January 1934 which confirmed the earlier evaluation.[6] The same year that the 73 year old founder Kintaro passed away. His legacy, Hattori & Co., had become the largest watch producer in the world, with factory output surpassing its main Swiss and American rivals.

Hattori was not interested in progressing watch-related innovation, nor developing watchmaking techniques. Instead he focused on adopting high-precision Swiss reference models, primarily Longines and Nardin watches[7], whilst developing and improving their technical skills.

In 1937, a Hattori subsidiary, Daini Seikosha Co. was founded to meet the growing needs of the Japanese military. They originally supplied five issued watches to the army and navy with wartime production peaking in 1940 at 1.3 million units.

The three military branches were originally supplied base metal chrome plated manual wind watches with different dial notations; an anchor for the navy, a star for the army and a cherry blossom for the air force. The latter had radium hands and dial markings.

Daini Seikosha dramatically expanded the employment of specialist production engineers, enabling the development of their own marine chronometer. By 1943, they had produced 500 pieces [8] essentially copying the Ulysse Nardin pieces the military purchased in the 1930’s.

The Seikosha factory production facilities were destroyed at the end of WWII, later rebuilt, and today the Seiko brand is an international juggernaut, and one of the most recognized international global brand names in the world.

The founder and man behind the legacy, played the greatest role in the invention, development, and progression of the Japanese watch and clock industry post the Meiji period.

Substantial credit also lies with Professor Aoki Tamotsu, who headed the Tokyo University Department of Arms Production (zohei gakka), the so called DAP, until it was renamed the Department of Precision Engineering (seimitsu kikai kogakka), in 1945.

He recognized the need for specialist horology artisan training and headed the Precision Industry High School (Koto seimitsukogakko). It was co-founded in 1933, by the Faculty of Engineering of the University of Tokyo, and the Horological Institute of Japan (Nihon tokei gakkai).[9]

He was one of the primary drivers of dramatic engineering improvements within Japanese industries in a range of sectors after visiting 84 international factories during a five-month trip in 1935. Aoki was most responsible for driving the need for production engineers in a variety of key core industries including precision watch engineering.

Early pre-WWII aviation and the war itself was a very dangerous game with a limited lifespan for almost all participants, especially pilots. Consequently, early aviation watches, especially military issued ones are highly sought after by collectors.

One of the most coveted and rarest Japanese issued military model of WWII is a 47mm aviator watch made by Daini Seikosha Co. from 1940 right through until the end of the war in 1945.

All evidence points to all watches for the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service being issued with consecutive numbering. At the moment the highest known Longines Weems IJNAS precursor has #1403 as an issue number.

Whilst issue numbers on the Tensoku have been seen as high as 7xxx, the lowest seen so far is 1474. This lends support to the consecutive numbering of military pilot watch pieces. The Weems arrived earlier and consequently most numbers are less than 1000. Given the precarious state of the Japanese war in 1945, military pieces including Tensoku were supplied without numbering, giving a likely total production of all pieces of IJNAS of less than 10,000 units.

The name given by the Japanese Tensoku Tokei (天測時計), essentially a celestial navigation timepiece, relates to the principle of maintaining the order of the universe, including the operation of celestial bodies, the order of the natural world, and also the way rituals and humanity should be.

This includes the requirement that both god and people needed a vow to keep these rules.

The Tensoku, a manual wind aviator’s watch was originally made using a 19 ligne pocket watch movement. The model features applied radium to both the hands and dial, a turning bezel rotates the inner chapter and large onion crown allows use with gloves. The chromed nickel case likely chosen because of available materials and the absence of the necessary tooling to work with stainless steel.

Pre WWII there appear to be a small sprinkling of Seiko steel watches, but little information on their manufacture from Seiko themselves. Did they make the cases or were the cases imported like other Swiss parts and perhaps stamped by them?

Essentially steel watches made by Seikosha appear post WWII with the odd anomaly. So called Staybrite steel was also protected under a Swiss patent. All this aside from any potential material shortages, Swiss parts embargoes and materials being channeled into other military equipment manufacture.

Whilst the exact production number remains a mystery, estimates based on known numbers of all IJNAS issued watches put production at less than 10,000. Which Japanese air units were issued them, who added the Kanji markings to the back, and where they saw action still await discovery.

Originally, the watch developed a reputation as a model for Kamikaze pilots among early collectors. Whilst this is possible, and likely for some, we know that they certainly saw action in other theatres of war in the Pacific and that only a small handful of pieces have survived.

Whilst extremely rare, coveted and sought after, it is not the rarest of all models supplied to the Japanese military in the lead-up to WWII. That claim can be made with issued Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service (IJNAS) Longines Weems pieces which incredibly were ordered and received by the American agent Wittnauer from 1937-1940, before importation into Japan.

The second Sino Japanese War started mid-July 1937, and was essentially a prelude to WWII, and eight years of continuous war followed for the Japanese.

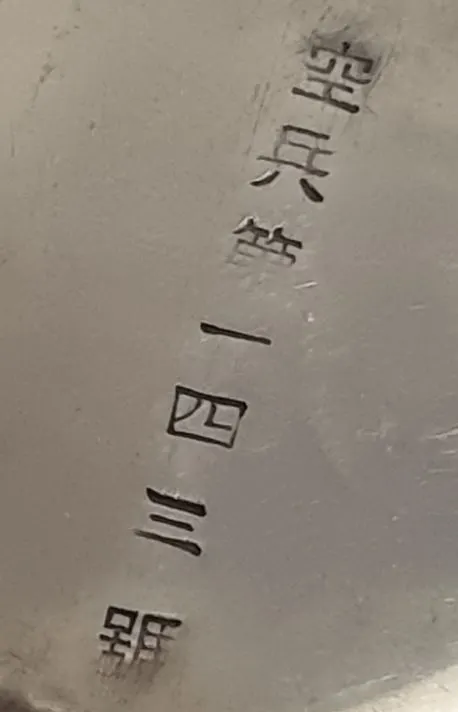

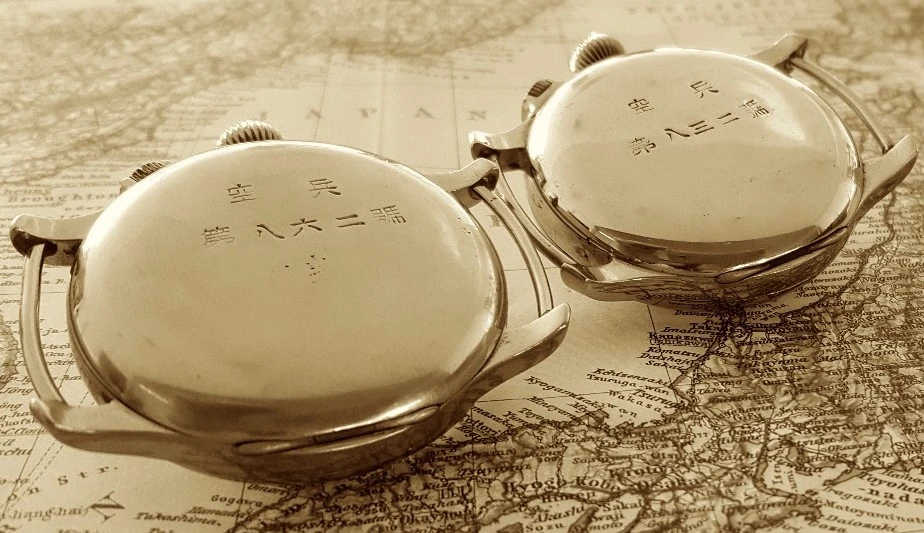

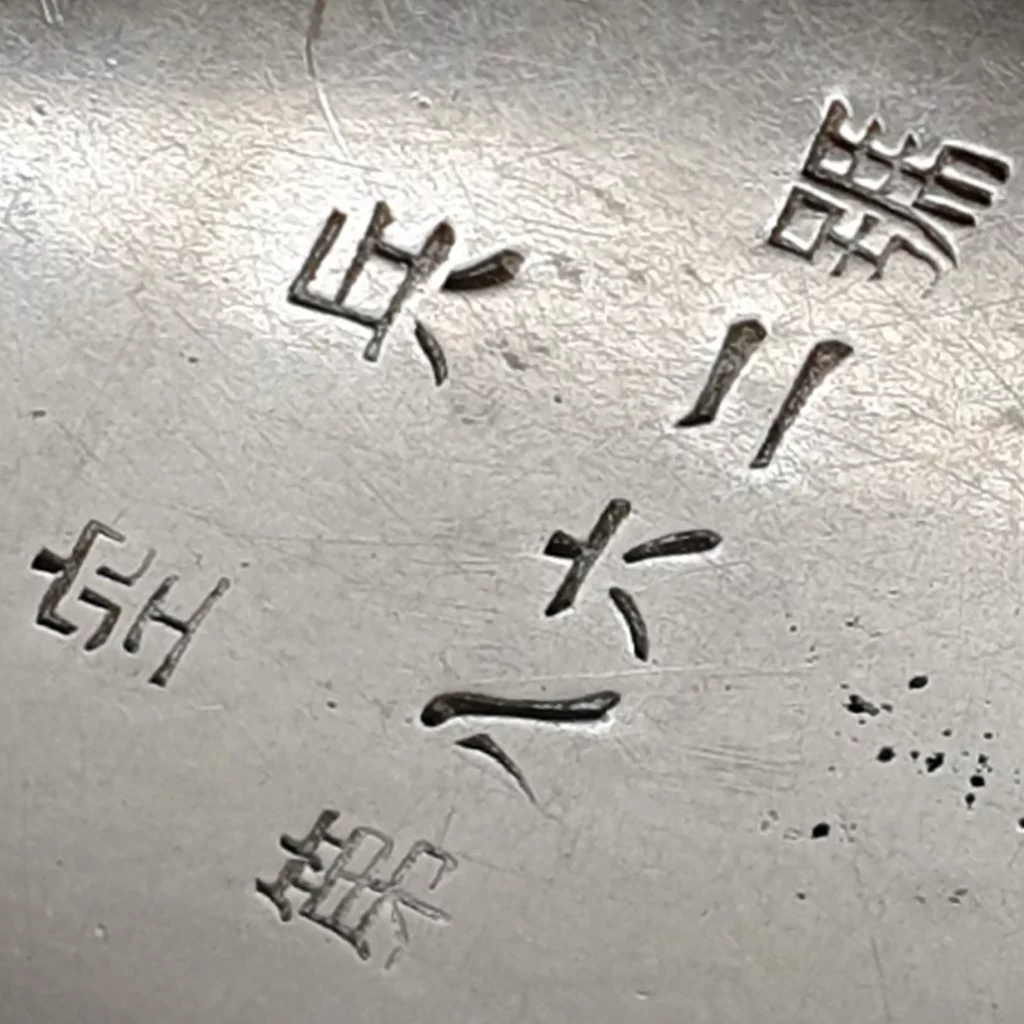

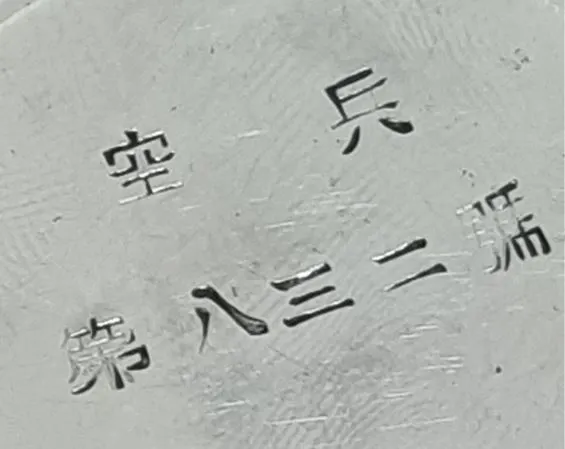

The Japanese have no equivalent word for Air Force, and the caseback of both the Seikosha pilot and the Longines Weems pieces feature Kanji characters (空兵). This literally translates to ‘Air Soldier’, along with a Japanese character for dai (a prefix for number), with the actual issue number.

In the 1930’s the Swiss watch industry experienced dramatic technological advancements in production techniques. Smaller and thinner, high grade, more complex movements appeared requiring new technology, tooling and machinery.

The Swiss employed cartels to protect their own industry from industrial transplantation, in essence limiting the supply of tooling and parts.

Whilst exports of certain kinds to Japan were banned in 1931, they still managed to smuggle required parts through other countries in the early stages of the cartel’s activities but the technological restrictions were an obstacle to Hattori’s later development. [10]

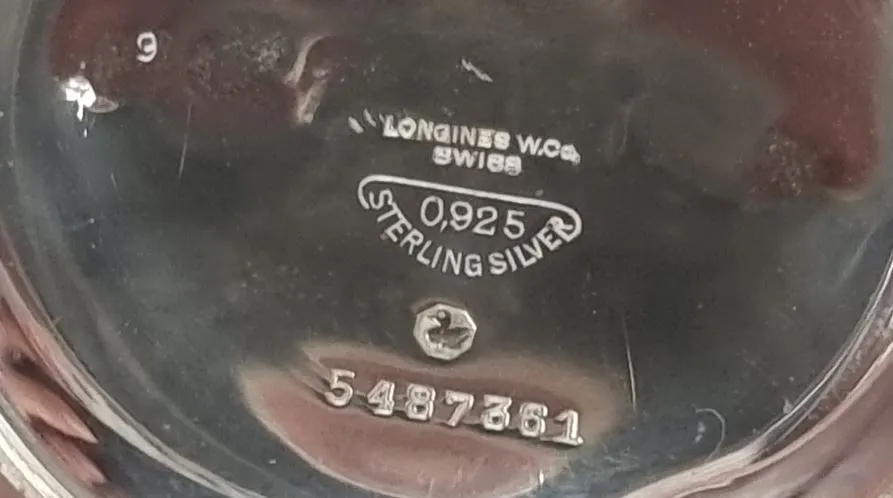

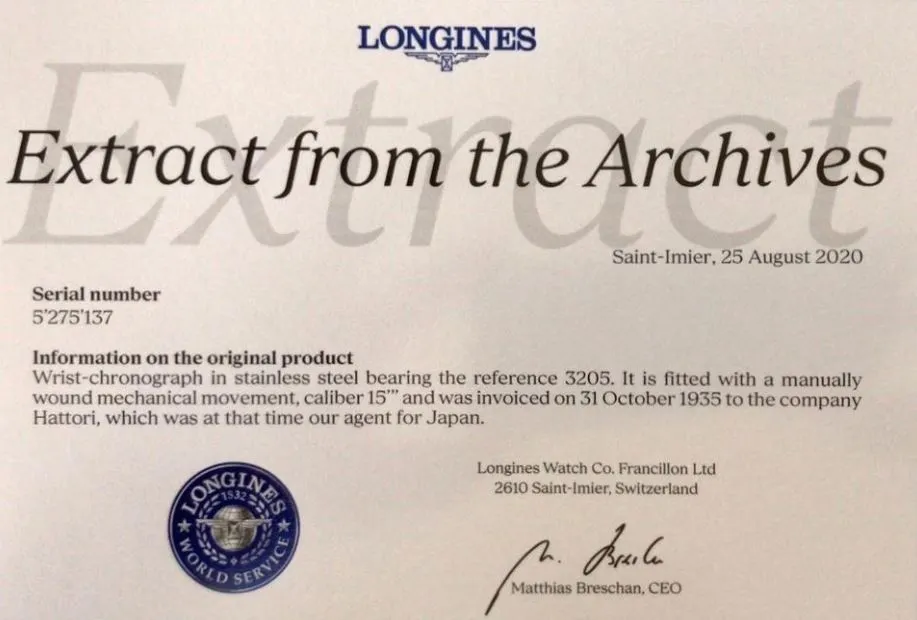

Two large Longines Weems models were supplied to the IJNAS and these pieces were used in the lead up to America’s involvement in WWII. The first, a small number of silver case Type A3 models with the 18.69N pin set calibre, ref 5350.

Today, just three examples are known to the market and whilst others may possibly exist, archives note delivery of less than 50 pieces in total. The first delivery of fewer than 20 examples was made Sep 17, 1937 just two months after the start of the second Sino-Japanese War.

These were most likely used by Japanese naval ‘Air Soldiers’ who were first active in China from July of that year.

For this model, the Kanji characters run in a single line down the middle of the back case and differ to the two separate lines of Kanji character case markings on the two steel models that followed in 1940.

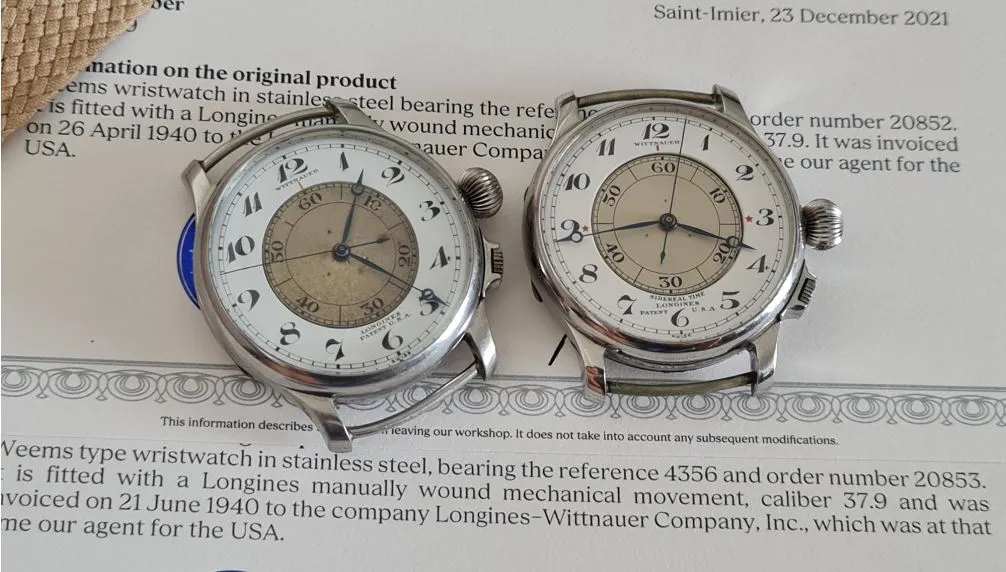

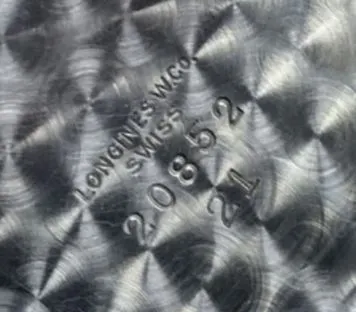

The second iteration are steel Type A-12 military designation pieces bearing ref 4356, and these account for the majority of known Weems IJNAS examples (just a handful or two). This reference uses a 37.9 calibre featuring a second crown at four to adjust the Second-setting function. These pieces were regulated for either sidereal or civil time and delivered on at least three separate dates in 1940.

The first of these, regulated for sidereal time, was delivered on April 26, 1940 per order #20852. When supplied, the dial on these pieces had two red stars at 3 and 9, to indicate adjustment for star time.

For almost all known pieces of this type, including IJNAS, the stars have been removed or damaged. The other, per order #20853 were regulated for civil time and noted in the archives. Both orders had approximately 200 pieces in them.

It has already been noted that watches regulated for sidereal time are generally used with a second timepiece running civil time. The consecutive order numbers of these Longines IJNAS Weems deliveries seemingly point to this.

Both were used by Japanese ‘Air Soldiers’ in the theatres of war in the Pacific and paradoxically, could quite possibly have been involved planning and/or in the attacks made by Mitsuo Fuchida’s aviators on Pearl Harbor in December 1941.

The last IJNAS Weems delivery is made June 21, 1940 which coincides with the introduction of the large brass nickel case Seikosha Tensoku watches which were first delivered in 1940/1. The Hattori company were importing Swiss watches from 1886, had a longstanding agency and import relationship with Longines from 1911.

The latter’s prowess and history in making aviation pieces and the accuracy and precision of their movements was well known. However, this was only one consideration for the Japanese and Hattori & Co in the selection process.

Longines were the only maker of the large Weems model, had the technical equipment, technology and available materials for making the steel watches the Japanese received in 1940.

Steel watches were rare in the 1930’s and whilst some Longines steel chronographs were known to be delivered directly to Hattori in October 1935, the patent for staybrite steel was owned by Thomas Firth John Brown Ltd, of Sheffield, and protected by Swiss patent #138647 from 1934.

The Weems used the pocket watch base calibres 18.69N and 37.9 at the time of Japanese deliveries. Given Hattori skills were significantly developed in this manufacturing space, having made their first pocket watch in 1895, it is highly likely they wanted a model on which to base their Tensoku aviator watch.

Daini Seikosha were not involved, nor interested in innovation. Earlier copying and modelling of Longines movements, alongside watch making machinery by Hattori confirmed this. Further, the known development and copying of Nardin marine chronometers in the early 40’s all support this reasoning.

The first steel cases on the Weems and Lindbergh models were first seen in 1938 and silver cases were still used into the early 1940’s on the Lindbergh model.

Many commentators submit that the second Sino-Japanese War commencing July 1937, was essentially the start of WWII. Long before Pearl Harbor, the Japan Imperialist expansion was afoot seeking to secure raw materials and labor.

The Swiss already had trading restrictions on parts, machinery, tooling and some finished goods flowing to Japan. Indirect imports circumvented some of these restrictions. However, in the lead up to and following Japanese attacks on China in 1937, further boycotts, trading restrictions and export bans were placed by the Americans, Swiss and others on steel, petrol, whole watch and parts exports to Japan. Given the indirect import of these Weems watches through America from 1937-1940 it appears the Swiss actions sought to protect their industry and punish Japan for its hostilities.

Further, the range of ongoing trade complexities wrought by the Great Depression itself grew Asian nationalism. The physical shortage of steel, the machinery required for processing it, and the lack of technical experience, and necessary tooling for making steel cases would also pose limitations and give rise to a range of supply difficulties for Seikosha.

Given Japan’s involvement in WWII from July 1937, it struggled with ongoing raw material supplies. Typically, military watches are made in quantity, and from available and at times lower grade materials. In the early stages of war, materials and watches were more available. However, not all not all Imperial Japan military personnel were issued timepieces and given the eight years of war for Japan, material supply issues abounded.

Seemingly little in depth study or writing has been made on the exact Japanese military process for their issued watches between 1937- 1945. If we look to other countries like Germany and their issuance of military watches, we see the following general rules subject to a few exceptions. Army watches were given to the individual soldier and entered into his soldbuch (identity papers), together with any other equipment he was issued with and they remained Wehrmacht (army/defence force) property. The soldbuch contained passport information, and included extra details about the soldier, including their rank, regiment/unit assigned to, equipment used, issued, and dates of leave.

However, pilot’s observers watches (Laco, Wempe, Stowa, IWC and Lange) for the Luftwaffe were issued on the day of use. Upon the return from their flying mission the pilots/navigators were debriefed and they had to hand back their watches.

They were then given to the next flying sortie. In all likelihood, this, or a similar process was most likely used by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service for both the Tensoku and IJN Weems issued watches.

The markings on the British Army watches were done by the Swiss suppliers whilst the markings on pilot’s watches were added by the Ministry of Defence (MOD). All timekeepers had to be returned to the military once the soldier retired from service.

The absence of historical Japanese photos of troops wearing a watch and the few surviving issued Japanese military watches in today’s market seems to confirm a much smaller military production. Further, it points to a reduced ongoing capacity to supply and issue, as well as reinforcing the scale of catastrophic devastation wrought by the nuclear bombing of the archipelago as WWII neared an end.

The Seikosha output was impressive and they were the only Japanese watchmaker capable of meeting wartime production needs. However, the limits of wartime itself, availability of materials and restrictions on access to new tooling equipment and technology ensured that steel watches were produced post war with perhaps the odd anomaly. The Seikosha factories had been destroyed by bombing in the latter stages of war.

The Japanese had already shown that they were not averse to buying the products, nor seeking the services of experts in the course of their incredible development and progress. Japan was one of the three greatest naval powers post WWI, along with the British and Americans.

Under the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922, an agreement was reached concerning a ratio of production tonnage between the five signatory powers. The Japanese authorities realized that they were lacking in skills and experience in the naval aviation space, and wanted to improve their naval air arm.

They willingly sought to enlist the help of expert foreigners post WWI and enlisted the English after assessing them to be at the forefront. The Japanese engaged the services of Captain William Forbes Sempill and 26 others, who arrived in Kasumigaura Naval Air Station in November 1921. The British brought twenty-five different model aircraft totaling more than 100 planes that were, and had been used by the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy.

The British team stayed for 18 months in what became known as the Sempill Mission. They trained the Japanese with the latest aerial weaponry, torpedos, cameras, military communication gear and a variety of training and techniques associated with take-offs and landings on boats.

Some of the planes would provide inspiration for Japanese designs that followed and whilst Japan was still dependent on England for much of the 1920’s, it was in the process of developing an effective naval air force.

The Japanese were a signatory to the London Naval Treaty of April 1930, and post event, drew up naval construction and replenishment plans known as hoju keikaku in 1931.

Unofficially known as maru keikaku, four ‘circle plans’ were drawn up in 1931/4/7, and 1939, creating the formidable IJN, which first saw considerable action in the Second Sino-Japanese War that started July 1937.

This expanded into the theatre of the Pacific, and the China War greatly aided Japanese naval aviation’s development demonstrating how aircraft could contribute to the projection of naval power ashore.[11] Naval carrier aircraft attacked military installations on the Yangtze and other parts of the mainland, including the bombardment of Chinese cities deep in the interior.

The two primary responsibilities of the IJNAS during their Chinese War: to support amphibious operations on the Chinese coast and the strategic aerial bombardment of Chinese cities – the first time any naval air arm had been given such tasks.[12]

America’s entry into war arrived December 7, 1941 after 400 Japanese planes attacked the American naval base and fleet stationed at Pearl Harbor, in what Roosevelt termed, ‘… a day of infamy’.

Japan’s naval zenith and potency of its air force arrived soon after in 1942, where they found themselves controlling large parts of the Asian mainland and patrolling large chunks of the Pacific. Logistical challenges abounded with supply chains stretched and the Americans industrial might came to the fore. The Japanese supremacy would not last and in the years that followed ended with a wholesale loss of life and property.

“In 1944 alone the Americans launched a force that rivaled in strength the Combined Fleet of December 1941. Such was the scale of the American industrial power that if during the Pearl Harbor attack the Imperial Navy had been able to sink every sink every major unit of if the entire U.S. Navy and then complete its down construction programs without losing a single unit, by mid-1944 it would still not have been able to put to sea a fleet equal to the one that Americans could have assembled in the intervening thirty months.”

– H.P. Willmott (Royal Historical Society)

War tremendously accelerated military technology including communications, radio and radar advancements and the need for military aviator’s timepieces.

Technological changes had already largely impacted the need for celestial navigation and the needs for specialist navigators and dedicated timepieces regulated for sidereal time largely disappeared. Save for a few stragglers by the end of the War specialist Weems and Lindbergh models heyday had largely passed.

The plane losses for all countries during WWII were horrendous. USAF archives note Japanese losses for planes in the air and on the ground somewhere between 35,000-50,000 pieces.[13]

Total plane losses of all nations in WWII is somewhere in the order of 379,000 units. [14]To put this into context, aircraft losses of every war by all sides since World War II amount to approximately 4,000.[15]

Japanese Kamikaze attacks estimates during WWII range from 2800-4000 with a supposed success rate of 19% for hitting the target. Flight Lieutenant Haruo Araki, one of the less fortunate souls embarking on such a mission, wrote this to his wife of just month…

Shigeko,

Are you well? It is now a month since that day. The happy dream is over. Tomorrow I will dive my plane into an enemy ship. I will cross the river into the other world, taking some Yankees with me. When I look back, I see that I was very cold-hearted to you. After I had been cruel to you, I used to regret it. Please forgive me.

When I think of your future, and the long life ahead, it tears at my heart. Please remain steadfast and live happily. After my death, please take care of my father for me. I, who have lived for the eternal principles of justice, will forever protect this nation from the enemies that surround us.

Commander of the Air Unit Eternity, Haruo Araki[16]

It is important to note that whilst many of those Kamikaze attacks were planned with a stripped down plane. The needs for navigation equipment and an Air Soldier timepiece on the wrist, for those choosing such a mission of no return, would have largely been negated. However, one can imagine that not all Kamikaze missions were planned from the outset and many an attack was launched by a Japanese pilot who originally set-off with a different purpose.

Volumes have been written concerning the human tragedy and economic cost of wars. Military aviation tragedies are most often catastrophic in nature, with loss of the pilot and the plane itself. In Japan’s case, the loss of at least 35,000 pilots speaks volumes of the human tragedy that WWII brought to those young Japanese men and all other nationalities involved. The catastrophic effects of the nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the last days of WWII cannot be overstated.

At least 150,000 people died in those two events alone, and the scale of this destruction, loss of life, and property damage cannot be captured in any words. There are very few surviving Japanese issued military watches and perhaps a baker’s dozen IJNAS ‘Air Soldier’ watches. The Longines Weems Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service issued watches are without exception among the very rarest special military watch of all nations.

Whilst there may still be the odd piece waiting to be discovered in Japan or America (taken at the end of the war) or lying unknown in a collection. Japanese shop, watch book, auction sales records, and collector pieces over the last twenty-five years, point to just over 20 known surviving examples in all three configurations.

[1] Seiko Museum online Development of the Japanese Timepiece Industry centered by Seikosha | THE SEIKO MUSEUM GINZA

[2] “The hybrid production system and the birth of the Japanese specialized industry: Watch production at Hattori & Co. (1900-1960)”, Enterprise & Society, vol. 12 no.2, 2011, p 361 | Pierre-Yves Donzé – Academia.edu

[3] “The hybrid production system and the birth of the Japanese specialized industry: Watch production at Hattori & Co. (1900-1960)”, Enterprise & Society, vol. 12 no.2, 2011, p 361 | Pierre-Yves Donzé – Academia.edu

[4] “The hybrid production system and the birth of the Japanese specialized industry: Watch production at Hattori & Co. (1900-1960)”, Enterprise & Society, vol. 12 no.2, 2011, p | Pierre-Yves Donzé – Academia.edu

[5] The hybrid production system and the birth of the Japanese specialized industry: Watch production at Hattori & Co. (1900-1960)”, Enterprise & Society, vol. 12 no.2, 2011, p 370 | Pierre-Yves Donzé – Academia.edu

[6] The hybrid production system and the birth of the Japanese specialized industry: Watch production at Hattori & Co. (1900-1960)”, Enterprise & Society, vol. 12 no.2, 2011, p 370 | Pierre-Yves Donzé – Academia.edu

[7] The hybrid production system and the birth of the Japanese specialized industry: Watch production at Hattori & Co. (1900-1960)”, Enterprise & Society, vol. 12 no.2, 2011, p 366 | Pierre-Yves Donzé – Academia.edu

[8] The hybrid production system and the birth of the Japanese specialized industry: Watch production at Hattori & Co. (1900-1960)”, Enterprise & Society, vol. 12 no.2, 2011, p 375 | Pierre-Yves Donzé – Academia.edu

[9] The Department for Arms Production of the University of Tokyo and the beginnings of the Japanese precision machine industry (1930-1960), Osaka Economic Papers, 2011 | Pierre-Yves Donzé – Academia.edu p42

[10] “The hybrid production system and the birth of the Japanese specialized industry: Watch production at Hattori & Co. (1900-1960)”, Enterprise & Society, vol. 12 no.2, 2011, p 372 | Pierre-Yves Donzé – Academia.edu

[11] Evans, David & Peattie, Mark R. (1997). Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887–1941. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press.

[12] Evans, David & Peattie, Mark R. (1997). Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887–1941. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press.

[13] WWII Aircraft Losses By Country – World War Wings

[14] WWII Aircraft Losses By Country – World War Wings

[15] WWII Aircraft Losses By Country – World War Wings

[16] The Divine Wind: Japan’s Kamikaze Pilots of World War II by Author Saul David, PhD | The National WWII Museum | New Orleans (nationalww2museum.org)

Special thanks to Paul Pfanner for all his help with German and other issued military watches and Allen Wu for his expertise on the Seikosha Tensoku.

Besides aviator watches, IJN aviators onboard Kanko (torpedo bombers) also used steel Seikosha pocket watches, enscribed “Flight Clock”, like their Air Force Bomber crew navigator counterparts.

As Emperor Showa, Michi Hirohito (reign 1926-1989) himself commissioned in both Army & Navy, presented a Silver Seikosha pocket watch to the top graduate of Naval aviator classes. Only the best pilot students received such imperial gift (Onshi), other branches (e.g. Naval gunnery) received a Silver fountain pen, dagger or even a Samurai sword .

Between and 1936 the Japanese emperial service imported British Longines watches.

A very big thank you Philip for your insights and knowledge in the space and the sincerest of apologies for the belated response. Andy