The Longines honor roll captures the heroes and heroines of the golden age of aviation & exploration. Longines History with Aviation is incredible and varied. Longines was an integral part of early aviation and the aviators who dominated the space.

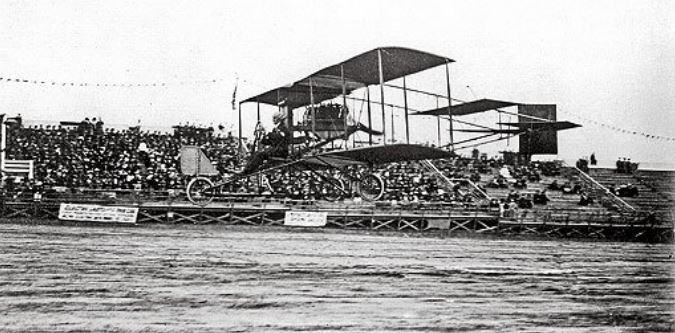

Planes, dirigibles, and balloons jockeyed for air supremacy, with the course of aviation history shaped forever during seventeen days in October 1910. Wellman’s dirigible America required a dramatic sea rescue after an unsuccessful Atlantic attempt, whilst Hawley and Post set a distance record in the Bennett International Balloon Cup, only to be lost in the wilds of Alaska.

The winner, the plane – after a nine-day aviation meet at Belmont Park, Long Island. Twenty-seven international pilots enthralled paying crowds who watched as speed, altitude, and distance records were broken.

It ended October 27, with the very first-ever race over a built-up area – around the Statue of Liberty, controversially won by the Frenchman, Henri Moisant.

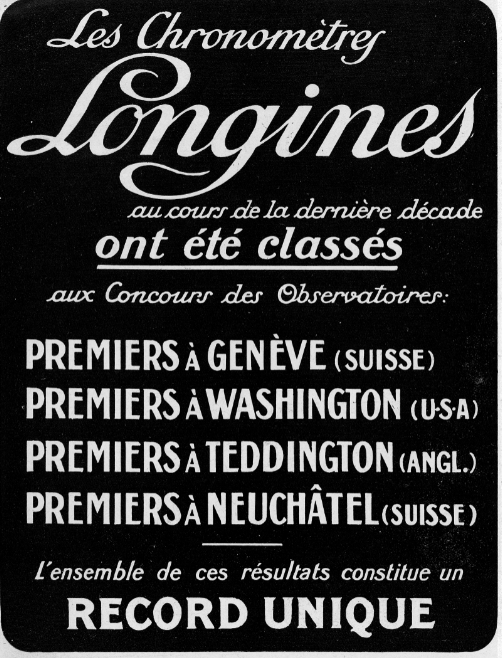

Longines won more precision timing and accuracy awards than any other maker from the four great observatories of the world – London’s Kew-Teddington, the US Naval in Washington, and those in Neuchatel and Geneva.

Absent radio beacons, satellites, and radar – an accurate, reliable timekeeper was relied upon for making navigational calculations, making the difference between life and death.

Longines had a formidable team – the technical prowess of Alfred Pfister, the American Longines entrepreneur and agent, Albert Wittnauer, and one of aviation’s greatest gatekeepers, and visionaries, John P.V Heinmuller.

Acquiring the nickname, ‘Aero One’, the latter departed St Imier in 1912, as a twenty-year-old, to join the American agent. With the Great War on the horizon, he was the key driving force behind the supply of Longines and Wittnauer cockpit instruments and plane calottes to the burgeoning U.S. Army Air Corps and other military forces.

Post WWI, the commercial and exploration aviation age had its own set of challenges. Almost no one could see the civil age of aviation that lay a few short years ahead, nor how to navigate there or in the air.

Longines became the official supplier of navigational instruments of the International Aeronautic Association in 1919.

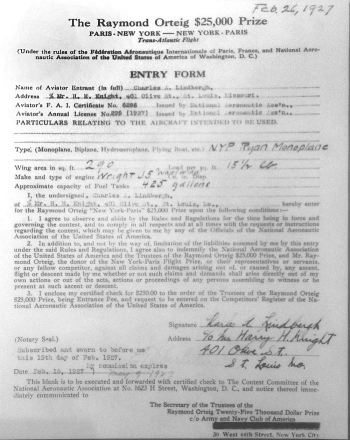

The same year French hotelier Raymond Orteig offered an incredible prize of 25,000 USD for a non-stop aviation crossing of the Atlantic, between New York and Paris, in either direction.

Challenges to the dominance of the Swiss watch industry abounded in America and elsewhere; Longines was not spared. The early 20’s were blighted with a business malaise – high unemployment, the doubling of living expenses, and dramatic inflationary pressures on raw materials. This led to complex workplace issues, reduced hours, strikes, and a collapse in watch manufacturing and sales in Switzerland and elsewhere.

Barnstorming, individually, or as part of a flying circus provided entertainment and enthralled the crowds. The nation’s airmen and women left over from the Great War, also sought to prove aviation’s potential and address aircraft vulnerabilities and expense in international competitions chasing speed, distance, duration, and altitude records.

Heinmuller’s commitment to aviation and horology was unrivalled. A pilot and watchmaker, he was soon vice (1921), and later president (1936) of Longines-Wittnauer, whilst serving as the chief timer of the National Aeronautic Association and the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale for 30 years. Much of the progress, success, and recognition of aviation’s greatest feats can be credited to Heinmuller’s friendships with aviation’s who’s who, his detailed record keeping, and his technical and aviation background.

Aviation and exploration exploits were a bright spot in the mid-twenties. There were larger, more efficient, and reliable performance engines, weight reduction with aluminum, and growing access to funding by entrepreneurs and governments who were starting to see aviation’s transportation and military potential – although this was challenging to acquire.

The Orteig prize created a race-like environment between Byrd, Lindbergh, the duos Chamberlin and Levine along with Nungesser and Coli. It was claimed by Lindbergh, on May 21 1927, at Le Bourget airfield in Paris, after a solo flight of 3620 miles, taking 33hrs and 39mins. One hundred and fifty thousand onlookers awaited the arrival of the soon-to-be ‘most famous man in the world’.

“Accuracy means something to me. ..I’ve learned not to trust people who are inaccurate. Every aviator knows that if mechanics are inaccurate. aircraft crash.“.

Charles Lindbergh

Lindbergh commented “I was astonished at the effect my successful landing in France had on the nations of the world. To me, it was like a match lighting a bonfire”.

Just ten days before he had flown from San Diego to New York in a record time of 21hrs 50mins. A few short weeks later Chamberlin and Levine’s New York–Berlin flight had Levine claiming to be the first passenger to cross the Atlantic nonstop.

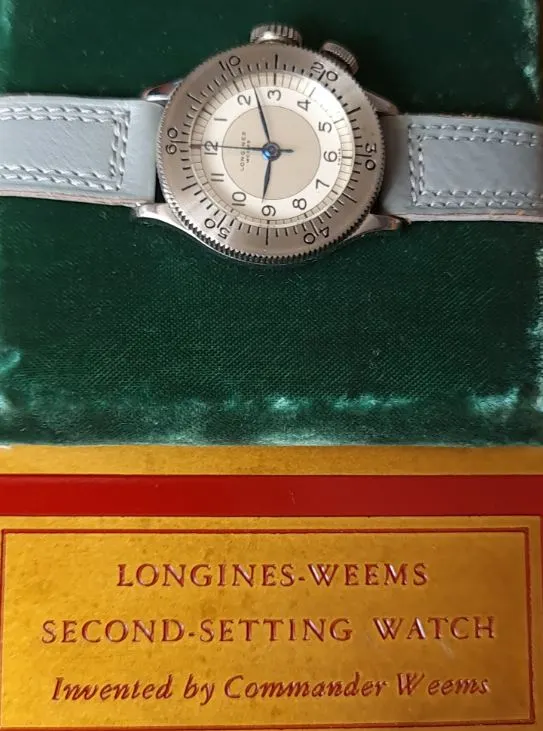

Whilst little is known of the watch worn on his successful Atlantic crossing in May 1927, Lindbergh later owned a hand-edited hybrid Weems, pictured in the Air Navigation book of 1931, and was the precursor to the most famous drawing and watch in Longines history.

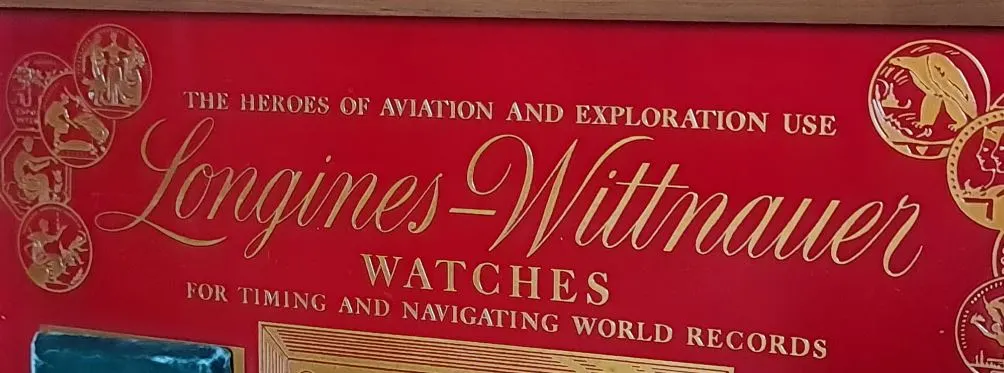

This environment gave rise to the most unique, incredible, and one of the most important “pieces” of all horological and an important part of aviation history. An enamel shop display that reads “The Heroes of Aviation and Exploration use Longines-Wittnauer watches for navigating and timing world records”.

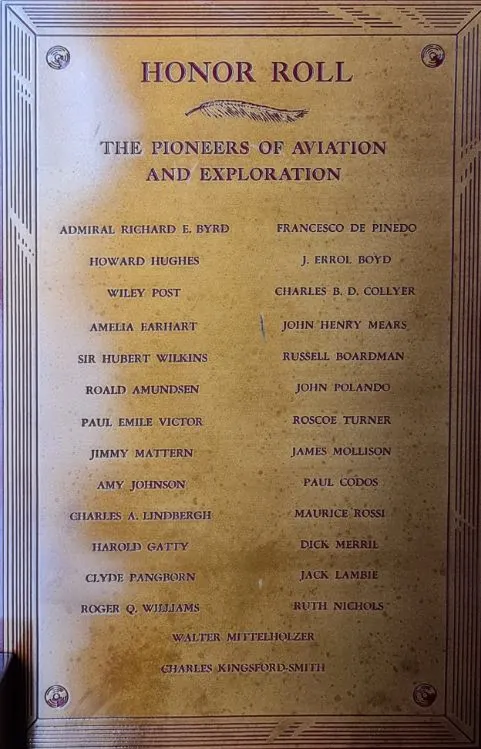

The late 1930’s stand, details twenty-eight of aviation’s greats, complete with the original pilot watches. World records were set, expeditions were successful, newspapers carried their stories of adventure, misfortune and success. Almost one-third of those on the honor roll paid the ultimate price for their ongoing commitment to aviation’s progress and development.

Almost all of aviation’s golden age greats relied upon a Longines, (or two), for their accurate, robust, technical navigation and aviation timepieces.

The names on the board and those within Longines ads from this period brought us the plane travel we all know today. Duration, speed, distance and altitude records were set, challenged and made again.

It is hard today for any of us to comprehend Lindbergh’s New York to Paris flight in a wicker chair, with an untested plane, limited forward visibility, limited navigation skills, some sandwiches just days after Rene Fonck’s Sikorsky bi-planes failure, and the loss of duo Nungesser and Coli trying to fly the voyage in reverse.

Lindbergh noted, “Accuracy means something to me. It’s vital to my sense of values. I’ve learned not to trust people who are inaccurate. Every aviator knows that if mechanics are inaccurate, aircraft crash. If pilots are inaccurate, they get lost-sometimes killed. In my profession life itself depends on accuracy”.

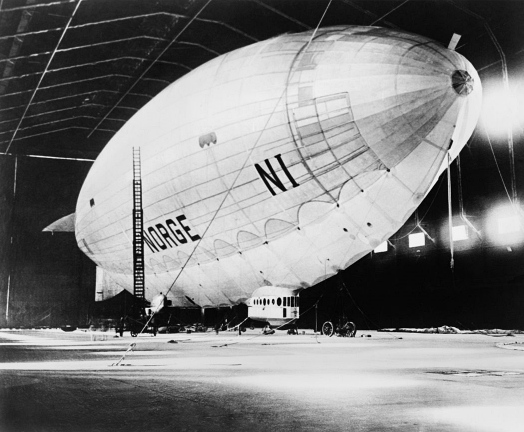

Longines chronometers were central to timing the North west passage exploits of Roald Amundsen, Byrd’s Atlantic trip in America, his multiple polar expeditions, and those of Umberto Nobile aboard his dirigible, the Norge.

The Pacific was first conquered by Kingsford Smith, speed records broken repeatedly by Roscoe Turner and the first ever non-stop westward Atlantic flight from Paris to New York, was made successfully by Bellonte and Costes.

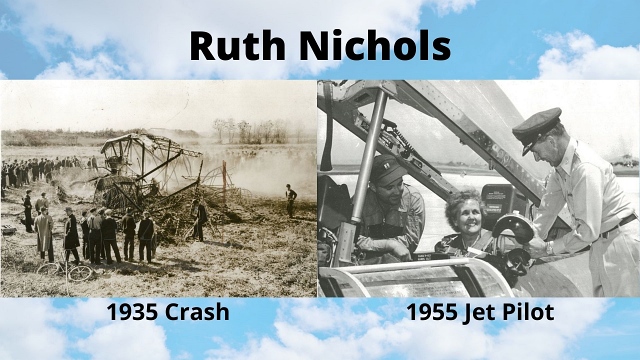

The aviatrix – Ruth Nichols, simultaneously held speed, altitude, and distance records using her 13.33 chrono in the mid 1930’s. After somehow surviving a near-catastrophic crash in 1935, she went on to be the first woman in a jet aeroplane just twenty years later.

In 1930, Amy Johnson was the first woman to fly from England to Australia after flying 11,000 miles solo in 19 days. She is pictured wearing a large Weems when learning celestial navigation from the grand master P.V.H Weems in May 1937. In less than four years, tragically her life would be cut stolen from her on Jan 5, 1941, crashing in bad weather and likely being reversed over during a botched rescue attempt.

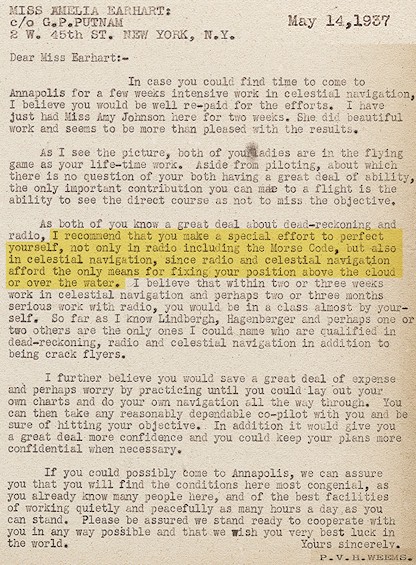

Whilst Amelia Earhart’s life and Atlantic success were cut drastically short because of aviation’s risks. A return letter from her secretary to Weems speaks of her inability to schedule the recommended navigational training before setting off for her ill-fated voyage.

Weems letter to Amelia Earhart shortly before her ill-fated adventure noting the value and importance of celestial navigation.

May 14, 1937

Longines watches were sold and literally went around the world on the flights of John Henry Mears and Charles B.D. Collyer in 1928, Harold Gatty and Wiley Post in 1931 and 1933, and Howard Hughes record-breaking 91-hour flight in 1938.

The golden aviation age was filled with excitement, trepidation, challenges, and zero margin for error. Disaster was commonplace, even for the famous seemingly “immortal” heroes who graced the display board’s honor roll and other Longines advertisements at this time.

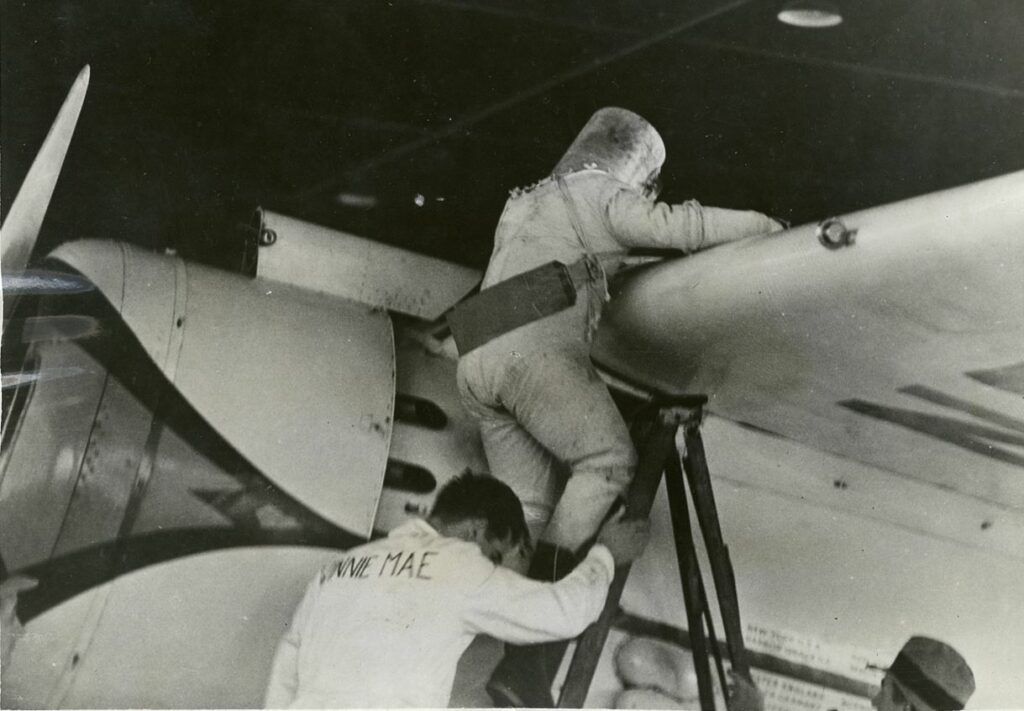

Perhaps nothing more illustrative of the dangers of aviation’s pioneer days than that of Wiley Post. He was the first to be aware and prepare for the effects of jet lag and studied sidereal time.

Incredibly, Post wore an eyepatch from an oil field accident, yet flew his famous plane, the Winnie May, twice around the world – in 1931, with Harold Gatty, and again solo in 1933, accomplishing perhaps what is to this day credited as the greatest aviation feat ever.

It is known Gatty used a large Weems watch personally, and he and Post used a pair of Weems watches and aircraft calottes for their “Around the World in eight days flight” in June 1931.

A few years later, in 1934, he went on to set an unofficial, (only denied by faulty instruments), altitude record of some 50,000ft in a propeller plane wearing the world’s first pressure suit.

The rubberized suit made by Goodrich complete with something looking like a diving bell. Perhaps more akin to preparations for undertaking a deep-water dive rather than the challenges of the stratosphere.

In tragic circumstances just nine months later, he lost his life with Will Rogers after their plane crashed into Alaskan waters from just fifty feet.

So too, Roald Amundsen a name synonymous with Polar exploration successes lost his life, on June 18, 1928 in a plane accident whilst on a rescue mission for the lost dirigible, the Italia, piloted by his friend, Umberto Nobile.

The pilots who avoided injury or worse, graced newspaper covers, and advertisements and were household names whilst their luck held. Their every conquest, journey, and adventure captured on the front pages of the newspaper and within, or on the radio.

Sometimes fortunate observers jostled for positions witnessing heroes, heroines, and history itself being made. On many occasions, life was ripped from them because of misfortune, misadventure, and challenges in the aviation space.

Out of seventy-eight attempted transatlantic flights up until 1944, just eleven were successful, with thirty-nine ending in complete catastrophe and the other failures without loss of lives. Today, monuments recognizing aviation’s pioneers grace airports, history books, and museums hold their stories and as a consequence, we enjoy flight of a truly different kind.

The Honor Roll display stand heralded from Utah and spent 65 plus years with 2 watchmakers past its heyday. Complete with all the watches, a black and white salesman’s photo also pictures two other displays connected with Longines aviation success.

These are – Wiley Post’s round-the-world voyage, as well as, Russell Boardman and John Polando’s flight to Turkey in 1931. Please give me a holler if you happen to find these in your travels ;).

The original packing crate is stamped ‘Longines technical display’ #11. Their role, and that of Longines air navigational timepieces, cannot be overstated. The ultimate navigational and aviation tool watches for men and women who braved all and often paid with their lives.

The stand and pilots of the honor roll speak volumes of a truly different time where aviators and aviatrix set about breaking records, committing themselves fully to the developing and progressing the aviation age. The immense challenges of early aviation and exploration pioneers have delivered an experience today that is very easy to take for granted.

The Honor Roll individuals and others in Longines print ads from this incredible and unique time are the basis for many of the chosen aviators bios and articles featured within this site.