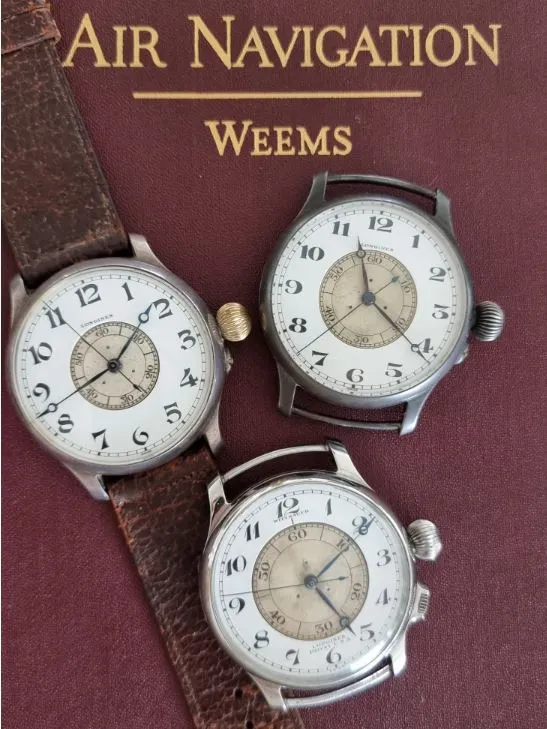

The first two prototype Longines Weems speak of one of the most exciting times of the twentieth century, the golden age of aviation.

Aviation’s Potential

Post WWI, the commercial and the exploration aviation age had its own set of challenges. Almost no one could see the civil age of aviation that lay a few short years ahead. The nation’s airmen and women left over from the Great War sought to prove aviation’s potential and address aircraft vulnerabilities and expense in international competitions chasing speed, distance, duration, and altitude records. Challenges to the dominance of the Swiss watch industry abounded in America and elsewhere; Longines was not spared.

The early 20’s were blighted with a business malaise – high unemployment, the doubling of living expenses and dramatic inflationary pressures on raw materials.

This led to complex workplace issues, reduced hours, strikes and a collapse in manufacturing and sales in Switzerland and elsewhere.

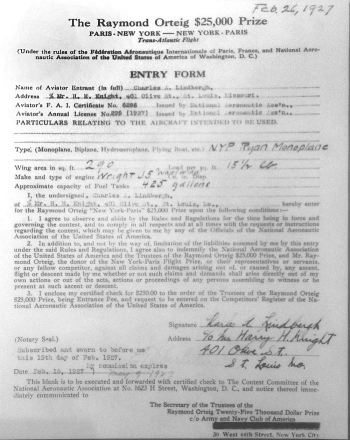

The Orteig Prize

Longines became the official supplier of navigational instruments of the International Aeronautic Association in 1919. The same year French hotelier Raymond Orteig offered an incredible prize of 25,000USD for a non-stop aviation crossing of the Atlantic, between New York and Paris, in either direction. Aviation and exploration exploits were a bright spot in the mid-twenties.

There were larger, more efficient and reliable performance engines, weight reduction with aluminum, and the growing access to funding by entrepreneurs and governments who were starting to see aviation’s transportation and military potential – although this was challenging to acquire.

The Orteig prize created a race like environment between Byrd, Lindbergh and the duos of Chamberlin and Levine, along with Nungesser and Coli. It was claimed by Lindbergh, on May 21 1927, at Le Bourget airfield in Paris, after a solo flight of 3620 miles taking 33hrs and 39mins. One hundred and fifty thousand onlookers awaited arrival of the soon to be ‘most famous man in the world’.

Lindbergh commented “I was astonished at the effect my successful landing in France had on the nations of the world. To me, it was like a match lighting a bonfire”. Just ten days before he had flown from San Diego to New York in a record time of 21hrs 50mins. A few short weeks later Chamberlin and Levine’s New York – Berlin flight had Levine claiming to be the first passenger to cross the Atlantic nonstop.

The speed of the plane brought complex new navigational challenges. When traveling at 200 miles an hour, a kilometer is covered in just eleven seconds. Countries, including island fuel stops, quickly disappeared – bringing oceans, uncharted territory, and a risk to life if navigational calculations were wrong.

Just as Harrison’s quest for the mastery of longitude, sea navigation and his development of marine chronometers almost 200 years earlier, air navigation came to the fore. Pilot’s lives depended on the reliability and accuracy of aviation timepieces and technical instruments as well as their ability to use them. Radio signal accuracy allowed perfect and easier time synchronization worldwide. This expanded significantly in February 1924, when the British Astronomer Sir Frank Dyson developed the famous BBC “pips” using two mechanical Royal Observatory clocks which became known as the Greenwich time signal.

The grandfather of today’s GPS system and the backbone of this air navigation age was Lieutenant Commander Philip Van Horn Weems (1889-1979). He was a pilot and master navigator who developed the essential second-setting watch and published a number of papers and books. His Weems System of Navigation training courses were adopted by the US Navy, commercial airlines, Byrd, and Lindbergh after his Atlantic success. Weems devoted his lifetime toward avigation (air as opposed to sea navigation) improving instrumentation and navigation techniques for long distance flying.

The Two Most Important Aviator’s Time Pieces

This remarkable time served as backdrop for the creation of the two most important aviator’s timepieces ever made: the Longines Weems ‘Second-setting’ watch which allowed for improved time synchronization, and Lindbergh’s ‘Hour-angle’ model, simplifying longitudinal calculations. With just a pair of hands and a dial, a watch could be used to calculate gasoline consumption, ground speed, load-lifting capacity, tell time and navigate using celestial observations.

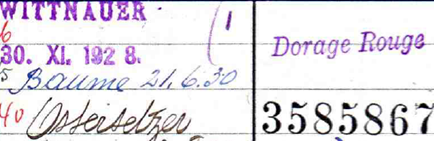

The very first Longines Weems made in an all silver case was delivered on the 30th of November 1928 to Longines-Wittnauer bearing serial number 3585867; the ultimate owner being none other than its original designer and architect, Philip Van Horn Weems who had developed the watch requirements with the Aircraft squadron’s battle fleet.

The central chapter on this new Longines Weems model allowed for the exact second to be set, relative to the hour and minute hands. The inner chapter ring disc could be rotated in either direction to gain an additional accuracy of +/- 30 seconds by using a radio signal or other known exact timepiece. Before 1928, watches were used with sextants for celestial calculations and accurate only to one minute.

Rear Admiral Moffett, who was the chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics for the US Navy Department stated “The suggestion… as to a moveable second-hand dial is considered to be a very valuable one, greatly facilitating the process of keeping a clock set to the exact time.”

Developed specifically for aviators with the Aircraft squadron’s battle fleet, it was officially designated as a “second setting navigation watch” by the U.S Naval Observatory. It was later distributed by them to the US Naval air stations and fleet along with filling private and government orders for the next twenty odd years.

Today Weems’s actual Longines ‘Aerochronometer’ watch, as described and pictured in his 1931 Air Navigation book lies in the Smithsonian, absent its crown, and is one of history’s most important pilot watches. Adopted by Weems, the name and part of its function lies with the man Lindbergh described as the “Prince of Navigators,” Harold Gatty. He used it to describe a timing device which offset aircraft speed inaccuracies when making navigational observations.

Weems Ideas Come to Life

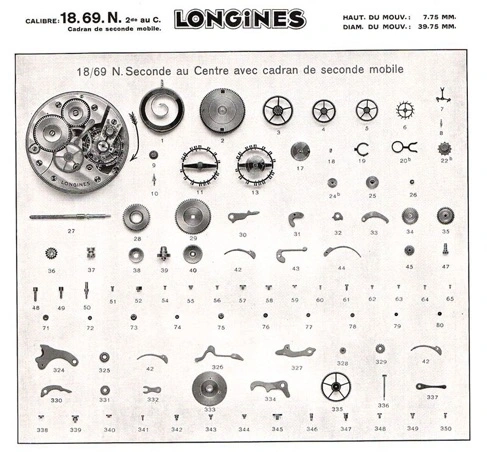

Weems’s ideas were first brought to life using modified Waltham Vanguard pocket watches, prior to the arrival of the improved and dedicated Longines wrist version. The first two Longines Weems pieces were prototypes using repurposed 18.69N pin-set pocketwatch calibers.

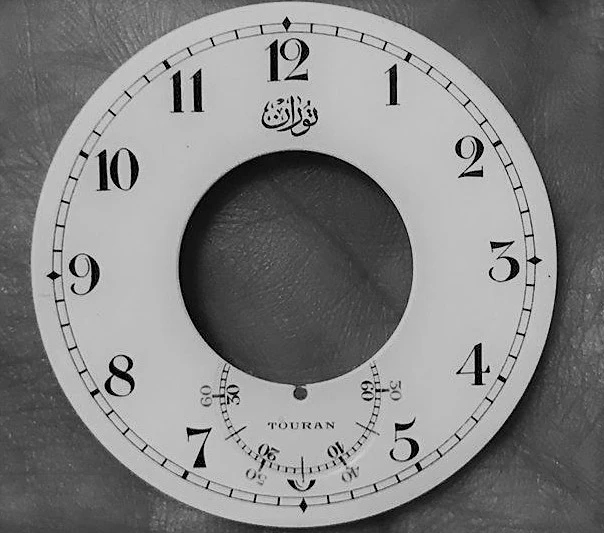

The 1918 movements had originally been destined for Duble tour D’Heure (dual time) pocketwatches, retailed by the Turkish agent, Nacib Djezvedjian. One can clearly see the genetic code of the Weems in the pocket watch dial.

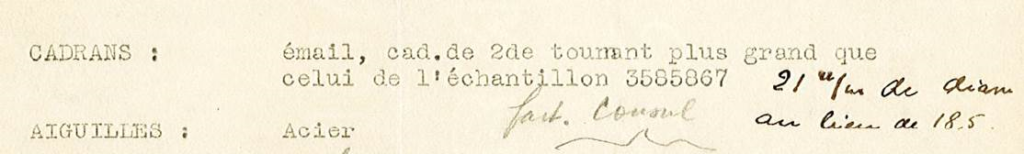

The large 47mm Longines Weems second-setting wrist watch, in an all silver case was born. The first two prototype pieces had unique 18.5mm experimental chapter rings, and this was noted in the archives. They both had gilded crowns and different dial fonts. The new model featured a double back, a turning metal chapter ring, blued steel full moon hands, an enamel dial, and a large onion crown enabling easier use with gloves.

For production pieces, first introduced in 1930, the chapter ring size was increased to 21mm and this includes Lindbergh’s actual Weems pictured in the same issue of Weems Navigation book.

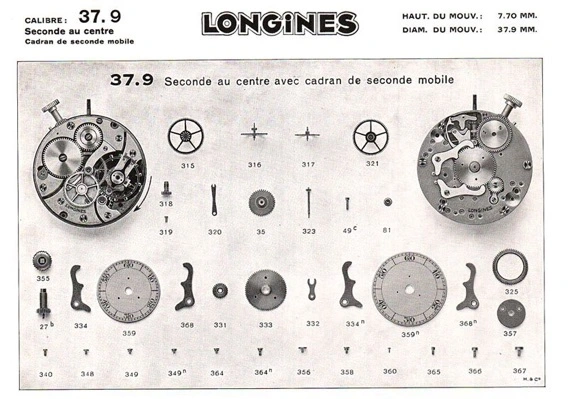

In or about 1938, the size increased to 25mm after the 37.9 caliber was used on the Weems model. A handful of experimental 37.9 pieces have the smaller 21mm chapter ring and an unprotected turning crown at four. The dissected movement illustration below also indicates two different sized chapter rings.

It would take five years before the 37.9 caliber first developed in 1932 would see use in a Weems and start replacing the pin set 18.69N. The turning crown at four enabled easy rotation of the inner chapter and the crown acquired shoulders or guards almost immediately. However, a couple of pieces have surfaced without the protective crown shoulders at four.

Delivery archives indicate a guard version being delivered before the version without. One suspects a few test pieces were made only and the guard model was chosen for the production market. One of these ‘test’ pieces lies with the Longines Museum and carries an unusual and quite possibly unique reference number 4214. The other carries the normal reference 5350. Both watches have dials that say Longines Patent USA at the six o’clock position and carry the third Wittnauer dial version of late 1937 on.

The Early Prototypes

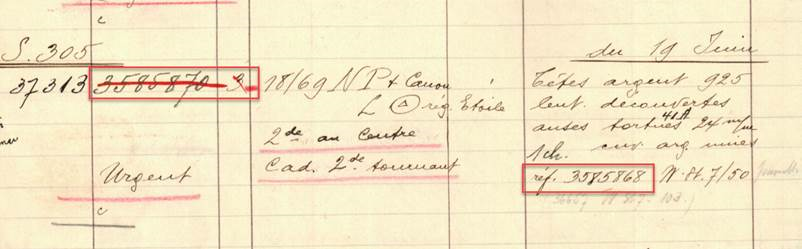

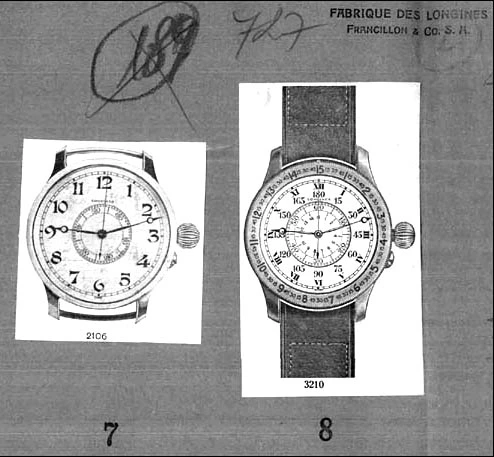

The earliest two prototype pieces were pre-reference numbers. Longines archives note a June 18, 1931 invoice to Perusset, the South American agent, of a Weems model 2106/5350 – the latter a cliché or picture number.

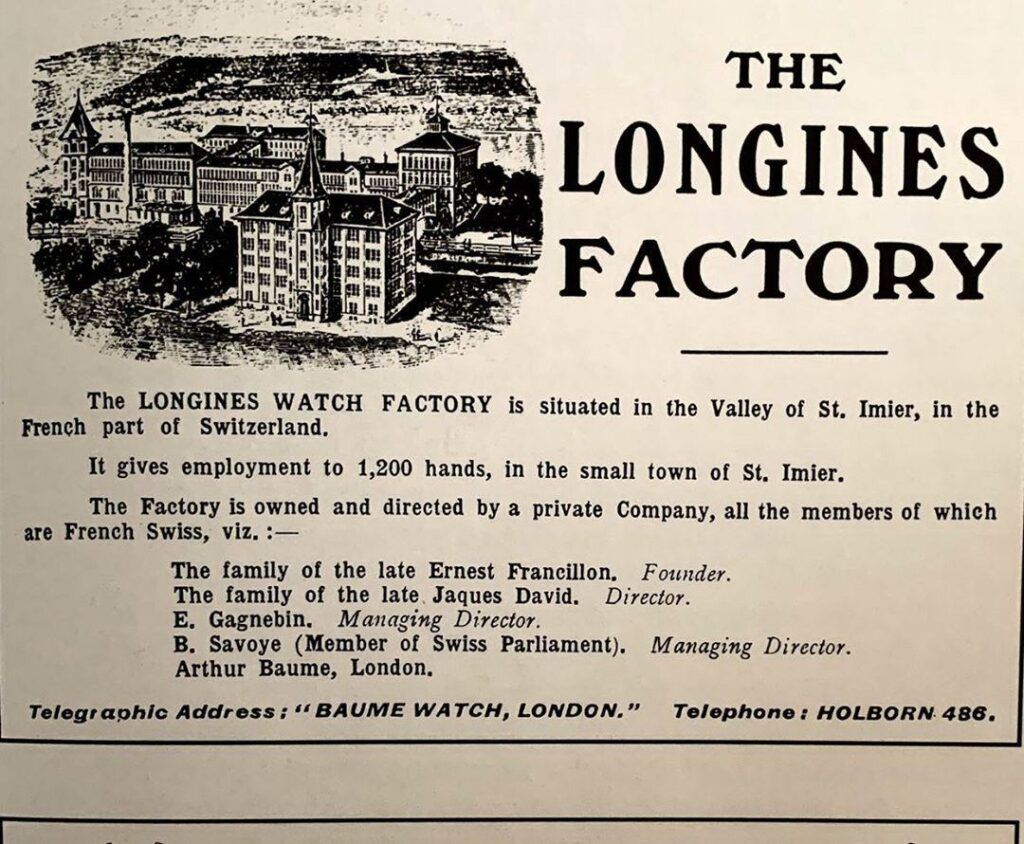

The second piece with serial 3585868 was delivered to the London agent Baume in June 1930. The case is signed AB (Arthur Baume) with a #1 on it. Case hallmarks indicate the case was made in 1929 and the completed watch was delivered June 1930 to Baume, making it the very first Weems watch ever delivered outside America.

The very first batch of production pieces were delivered to Wittnauer, May 2, 1930. Longines records have just a single cliché picture for this reference 2106. It is highly likely that the second Longines Weems piece ever made, a prototype, is the actual Longines catalogue picture because of the unique qualities noted.

The first two Longines Weems prototype wristwatches have incredibly both survived to tell their story and are two of the most important pilot watches ever made. The Weems second-setting wrist watch in the large case was only ever made by Longines, whilst smaller versions were made in later years by Longines, Omega, Jaeger, Zenith and Movado as the world headed to war.

The larger Weems model graced the hands of aviators and aviatrix who risked all in their commitment to early aviation’s development and progress in a truly different time. It was the pen-ultimate tool watch; robust , accurate and functional, overcoming the complex difficulties of setting a second hand. It allowed easy, instant adjustment and synchronization with the radio signals of the day.

The Weems second setting watches were relied upon by aviation’s who’s who in an age of Air Navigation, where accurate timing instruments and synchronization with a radio broadcast were truly critical. The speed of the aircraft brought the the age of Avigation; air, rather than sea navigation to the fore.

A watch error of 30 seconds could effect one’s calculation of position by many miles meaning the island fuel stop, and the island itself, simply disappeared bringing disaster. The man most responsible for conquest of aerial avigation in aviation’s golden years was PV.H Weems. Heinmuller, along with the technical team at Longines brought life to Weems ideas and created timepieces and instruments that pilots relied upon with their lives for conquering the challenges of flying over oceans, at night, exploring new lands and poor weather as aviation’s frontiers exploded.

The unique chapter ring size of these first two pieces, the “urgent” requirement noted in the archive, along with the repurposing of 18.69N dual time pocketwatch movements point to an age where avigation’s needs demanded timely, ongoing, and expedient innovation.