Lindbergh had a special Weems! It almost sounds like a chicken or egg type scenario, but in real terms it is a true “Lucy” in horological anthropology.

Whilst little is known of the watch worn on his successful Atlantic crossing in May 1927, Lindbergh owned two Weems, a Waltham Vanguard modified pre-Longines pocketwatch variety and a special piece from Longines.

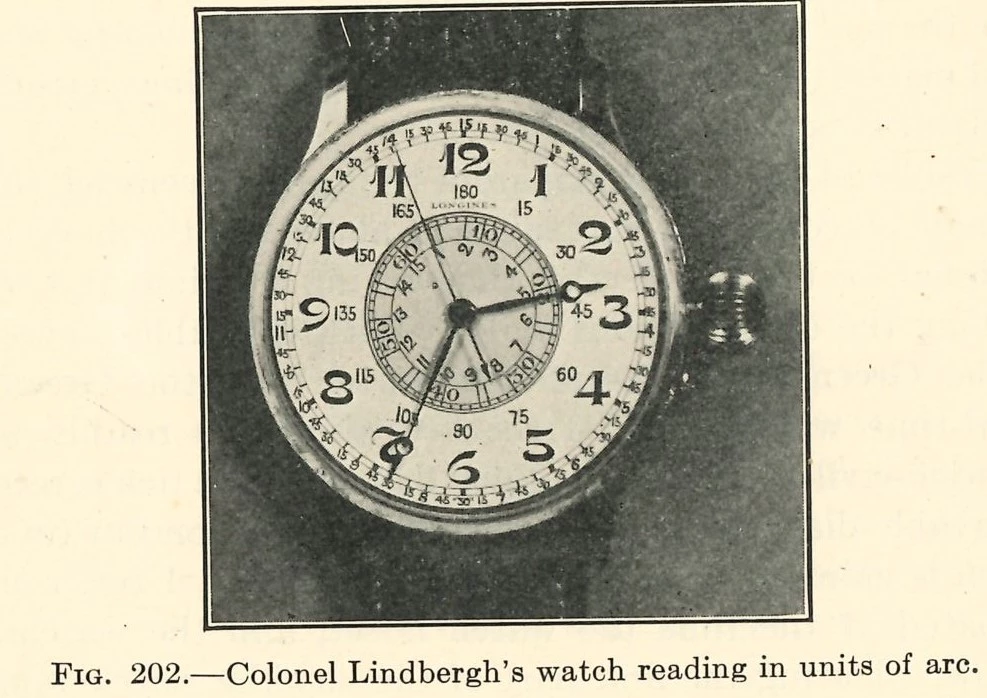

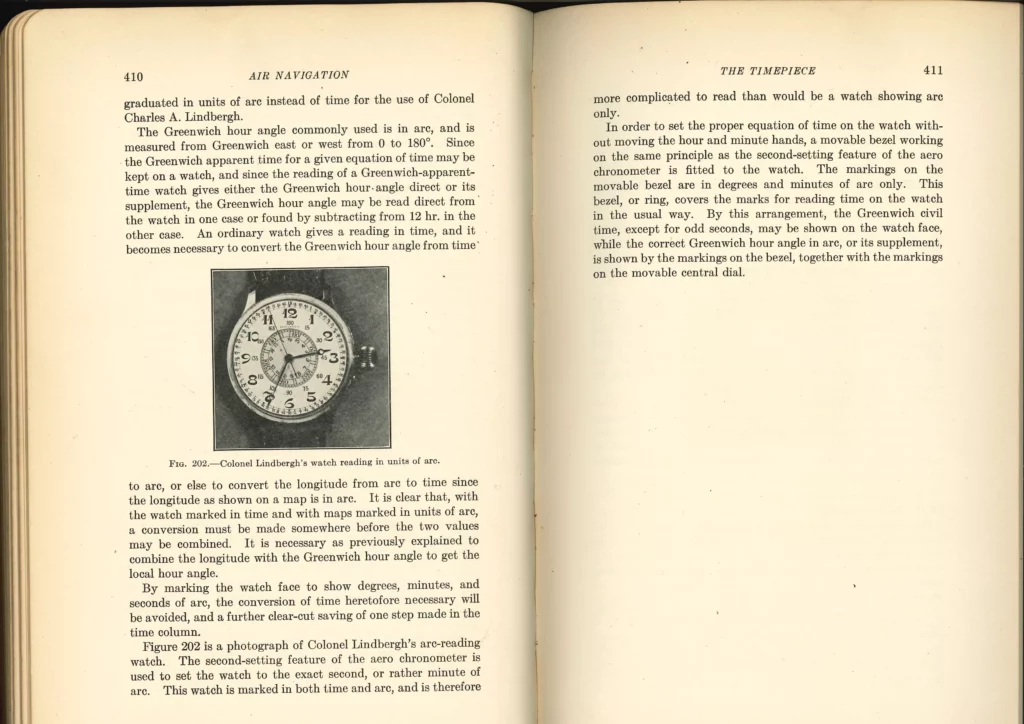

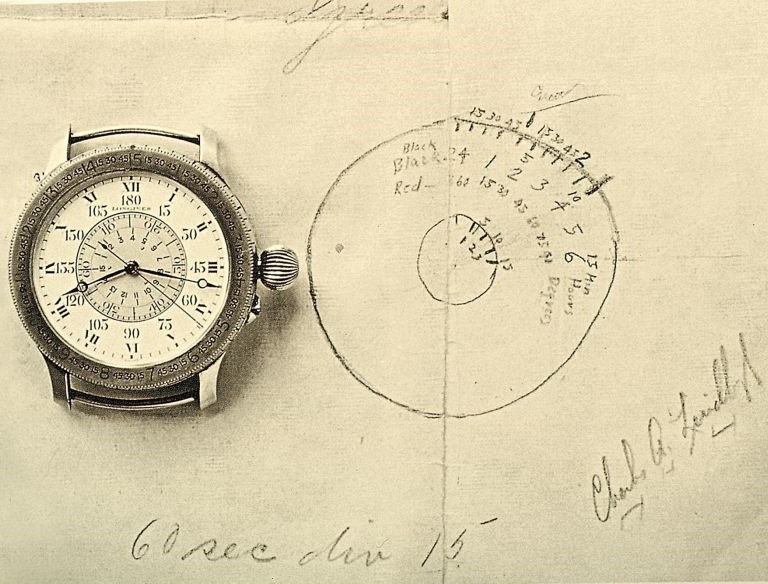

The latter is pictured in Weems Air Navigation book first edition, published in 1931. The watch was a hand edited hybrid Weems of sorts, with a dial featuring notations for units of the arc.

A what?

Long known as “Lucky Lindy”, he became the most famous and popular man in the world following his successful Atlantic crossing. He believed his Ryan Air M-2 ‘Spirit of St Louis’ complete with wicker chair to be it!, and stated in the New York Times that “As a matter of fact, I had what I regarded and still regard as the best existing plane to make the flight from New York to Paris.”

Pilotage and Dead Reckoning

Lindbergh used pilotage and dead reckoning navigation skills on his incredible historic Atlantic crossing. Europe is a large target, a post event analysis by the National Aeronautic observer, John Heinmuller, pointed to a unique Atlantic pressure distribution event at the time of Lindbergh’s flight. Essentially an incredible net wind drift of zero, had Lindbergh hitting the Irish coastline within a few miles of target.

Lindbergh noted “The first indication of my approach to the European Coast was a small fishing boat which I first noticed a few miles ahead and slightly to the south of my course.…..I have carried on short conversations with people on the ground by flying low with throttled engine, and shouting a question, and receiving the answer by some signal. When I saw this fisherman I decided to try to get him to point towards land….. In all likelihood he could not speak English… However, I circled again and closing the throttle as the plane passed within a few feet of the boat I shouted, “Which way is Ireland?” Of course the attempt was useless, and I continued on my course.“

‘Lucky Lindy’ took on new meaning, given the pressure system’s net zero drift outcome was recorded by weather experts for the very first time. His successful crossing soon made him the most famous man in the world, not an Atlantic statistic. What a difference a day makes.

The speed of the plane brought complex new navigational challenges. When traveling at 200 miles an hour, a kilometer is covered in just eleven seconds. Countries (including island fuel stops) quickly disappeared – bringing oceans, uncharted territory, and a serious risk to life if navigational calculations were wrong. Just as Harrison’s quest for the mastery of longitude, sea navigation and his development of marine chronometers almost 200 years earlier, air navigation (avigation) came to the fore.

After conquering the Atlantic, Lindbergh nearly suffered a tragic outcome after getting lost in ‘The Spirit of St Louis’ on a flight from Cuba to Florida… a haywire compass, stars shrouded in haze, and nothing recognizable from pilotage on the Florida map. Lindbergh’s inexperience and the challenges of air navigation (avigation) led to a meeting in 1928 with P.V.H Weems, a young naval officer who was an instructor at the Naval academy in Annapolis. The outcome likely changed avigation forever.

In 1928, after taking up training with Weems, a public conversation about avigation started within the aviation community. At the time the New York Times wrote,

“It will be news to…millions that Colonel Lindbergh needs to be taught navigation…. If the Colonel doesn’t know how to navigate, who knows anything about anything?”

Lindbergh’s successful Atlantic crossing had many believing that transoceanic air navigation was fate and a matter of determination. In much the same way that Harrison’s conquest of sea navigation had brought certainty to the longitude issue that plagued mariners. Innumerable lives were lost in air due to a different set of navigational issues.

Lindbergh took up studies in celestial navigation and star altitude curves which greatly sped up the determination of position. With the help of star charts and Polaris (the northern star) the navigator was able to help clarify his possible position using two stars in a little over 30 seconds.

Another Weems book Line of Position almost had Lindbergh instructing himself. The development Weems second setting watch in the Longines wristwatch form allowed for +/- 30 second adjustment, dramatically improving time synchronization with a radio signal and avigation itself.

A watch error of thirty seconds could have catastrophic consequences and represent an error of seven and a half miles difference in one’s longitude position near the equator, missing an island or the desperately needed fuel it provided. Pilot’s lives depended on the reliability and accuracy of aviation timepieces and technical instruments as well as their ability to use them.

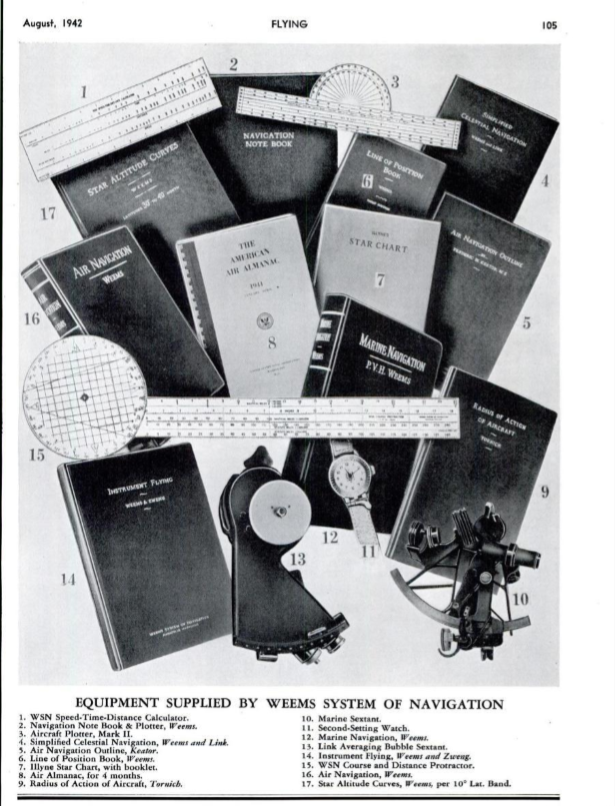

Given Lindbergh’s notoriety, and his willingness to note his own air navigation shortfalls, Weems was able to draw attention to the complex Air navigation issue challenges. He launched an aerial consulting business with his first school in San Diego, collaborating with, and soon employing Harold Gatty who joined the stable as chief instructor.

Gatty was soon using the full suite of Weems System of Navigation books and techniques, consulting to the American military, and the commercial airlines of American Airlines, TWA and Juan Trippe’s Pan Am. The latter had engaged Lindbergh to develop a variety of transatlantic routes.

Longines Weems Watch

Was Lindbergh’s Weems the precursor to the most famous drawing and watch in Longines history? Weems wrote comments during the publication of Weems Air Navigation book (published 1931) that Longines were working on a graduated dial in arc, not time, along with “… a moveable bezel working on the same principle as the second-setting feature of the Aero Chronometer is fitted to the watch. The markings on the bezel are in degrees and minutes of arc only.”

Lindbergh’s Weems featured the standard 21mm internal chapter ring of production models which were first delivered in April 1930 to Wittnauer. Only a couple of pieces are known to exist with the early Art Nouveau style font and one of these lies in the Longines museum. The author opines that Lindbergh’s piece is likely a piece from this very first production batch, and modified shortly after receipt (most likely with Weems) whilst he waited for the arrival of the hour angle watch he designed.

To date, just two pieces have surfaced and known to exist with the early font matching Lindbergh’s piece. One of these resides in the Longines museum and the other piece below delivered in the first commercial production delivery of Weems, delivered on May 2, 1930, to Wittnauer.

The Hour Angle Watch

Heinmuller met Lindbergh shortly after he broke the US transcontinental speed record from Los Angeles to New York on April 20, 1930. In a letter to his wife, he wrote “…I was privileged to work out details of his latest instruments with him as the enclosed design from him will show. Keep it for our records. His latest ideas incorporate a second setting device for Greenwich Time, taken from the radio. The device… permits laying down of a position in less than three minutes. Navy experts at Annapolis say it is the most outstanding aviation improvement in many years”.

The hybrid Weems watch, Heinmuller, Weems himself, and the Longines technical team in St Imier were the formative pieces bringing life to Lindbergh’s famous drawings, and production of an Hour-angle prototype in October, 1929. There are two known Hour-angle prototypes. It is likely that both (a turning bezel version and the other with dial notations only, our Lucy were both delivered to Wittnauer either April 10, or May 1930. Refinements and improvements were made and Lindbergh commented he was examining the watch in a letter to Heinmuller in February 1931, and commented on it’s perfect timing in July of the same year.

A patent request was filed for history’s most famous pilot watch, the Hour-angle, in October 1931. Lindbergh’s ‘Hour-angle’ model enabled and simplified longitudinal calculations. With just a pair of hands and a dial, a watch could also be used to calculate gasoline consumption, ground speed, load-lifting capacity, tell time and navigate using celestial observations.

The Weems second-setting watch played a crucial role in the progress, development and challenges of Avigation. The speed of the plane brought a range of complexities not present with sea navigation. When next sipping a gin and tonic (if that is your thing) in the flight lounge, or on board, spare a thought for the historical watches of mastermind P.V.H Weems, the grandfather of today’s GPS system and the incredible characters who wore them. Weems is ‘that’ someone who played an integral part to making it all possible.

The so called ‘Aerochronometer’ and Weems personal watch from Weems Air Navigation book lies in the Smithsonian. The whereabouts of one of Lindbergh’s incredible Hour-angle prototypes, the world’s very first turning bezel wristwatch has been discovered. However, the location of “Lucy”, a rare Flightbird and his hybrid ‘missing link’ Weems hour-angle watch, remain a mystery.