Referred to as a ‘Natural-Born Flyer,’[1] Roger Q. Williams Pathfinder, first found recognition in the aviation circuit when breaking the over-water flying record in 1929. He and Lewis Yancey flew from Old Orchard Beach, Maine to Santander, Spain covering 3,400 miles in 31 hours and 30 minutes. With this and many other records under his belt, Willimas was a shoo-in for the Longines Honor Roll.

The Pathfinder, their appropriately named Monoplane ‘had to fly blind through the fog for much of the first part of the flight, but Yancey’s extremely accurate calculations (probably aided with the use of this Longines chronograph pocket watch) kept them on course.’[2]

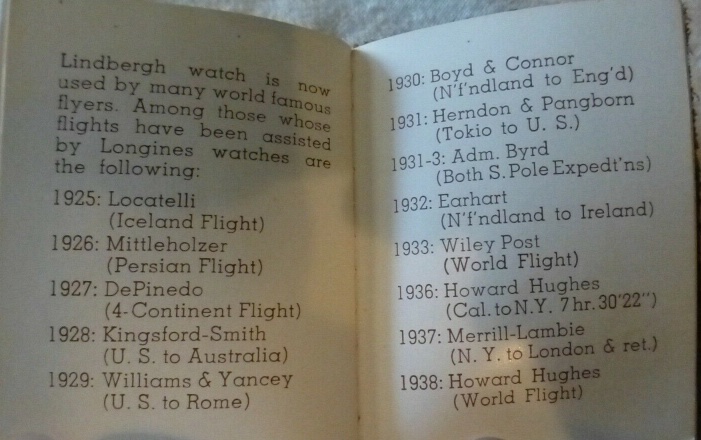

The image below is from the 2011 live auction at Christies. The pair of timepieces shown below realized 68,750 CHF.

After minor repairs were made in Spain, Yancey and Williams arrived in Rome to a crowd overjoyed, cheering enthusiastically in light of their achievement. They were the very first pilot’s to undertake a flight from the United States to Rome.

For this Williams was awarded the Grand Master of the Order of the Crown of Italy by King Victor Emanuel, and the Gold Medal of the Minister of Aeronautics of Italy by Premier Benito Mussolini. The Vatican itself bestowed a Special Decoration upon Williams.

After this successful record-breaking flight, Williams made a non-stop, round-trip flight from New York City to Bermuda, Hamilton on the 29th of June, 1930. The 1,560-mile flight was completed in 17 hours and 8 minutes in the Wright-Bellanca WB-2 aircraft named Columbia.

The plane itself had no radio or lifesaving equipment[3] leaving no real room for error. Williams, upon his return, recalls a potentially fatal storm close to Bermuda: within forty miles of the island, we struck one of the fiercest rain squalls I ever saw. We went down to 200 feet and came in over the city and circled. It looked like a landing on a field I couldn’t see, as water got at the magneto and the engine began to kick up. We circled for twenty minutes hoping for a place to land or a let-up in the rain. Finally, we turned seaward again. A few miles out the rain stopped, the sky cleared and the old motor started doing its stuff again. [4]

Riding through the storm Erroll Boyd, Roger Q. Williams, and Harry P. Conner sought to ‘prove the feasibility of a regular passenger service between New York and Bermuda.’[5] They circled the tiny coral island without one landing from start to end despite the faltering engine and the impossible visibility.

They achieved their intended objective and as of June 16th, 1937, Pan American and British Imperial Airways inaugurated flying boat services from New York to Hamilton. The duration of flights cut dramatically at 4.5-5.5 hours for a 1-way journey.

What Williams did not mention was that they had dropped a bag of mail on the Belmont Manor Golf Club grounds, to the rear of the Hotel Bermuda. When a reporter asked him about landing there, Williams said the golf course was the only possible stretch of land where a landing might have been possible, but that a crackup was ‘certainly a possibility.’ [6]

The return flight to New York was uneventful. They made a night landing at Curtiss Field instead of Roosevelt Field because of thick haze over their departure airport. The elapsed time for the 1,560-mile flight was 17 hours 8 minutes, and they had enough fuel remaining to fly another 1,000 miles. The trip served as a practice run in the same Bellanca for a transatlantic flight by Boyd and Connor from Newfoundland to England the following October. [7]

These flights would mark the first commercial journeys from the U.S. to Bermuda. Just 21 years later, in 1951, commercial passengers taking this route totaled 12,000 during the Easter season. Initial flights like Williams’ Bermuda course were instrumental in taking the general population to new places, broadening their horizons, and offering new opportunities to aviators and citizens alike.

Born April 30th, 1894, in Brooklyn, New York, Roger Q. Williams went on to break aviation records, to design the Yankee Aerocoupe, and to become known as Aviation’s Apostle.[8]

He furthered the prominence of commercial aviation through a series of extensive tours from 1939 through to 1940. Sponsored by Reader’s Digest Williams visited 177 cities in 17 months.

He held talks on aviation in front of 150,000 people overall. This included 27 radio presentations which reached a further 2,000,000 people. During these talks, he spoke of the difficulties facing aviation, the fears and skepticism that held people back, and how to resolve these issues.

During the closing remarks of each talk, he offered to take first-time fliers into the air for free. His Fairchild aircraft logged over 380 hours, covering 48,000 miles with 3,400 first-time fliers made airborne. He offered the opportunity for those who had had never flown, who were anxious of flight or who would not have had the opportunity to fly within their lifetime.

Williams wholeheartedly believed in commercial air travel, accessible to all. Within his lecture, he stated that ‘aviation is here to stay. If you don’t fly during your lifetime, you may accept it as an incontrovertible fact that your children and grandchildren are going to shake off the shackles of the earthbound and bring themselves a new sense of values which getting up in the clouds engenders.’[9]

Understanding the liberation aviation could offer, Williams endeavored to share his findings with all he met. He established The Roger Q. Williams School of Aeronautics within his lifetime, lectured and wrote books such as To the Moon and Halfway Back in 1949 and Up Currents in 1947. He served with the United States Army Air Corps in WWI and with the United States Army Air Forces in WWII.

Upon his death on August 12th, 1976, he was a member of the Quiet Birdmen, National Air Pilots Association, International League of Aviators, World Flyers, American Legion, Chicago Press Club, Royal Aero of Italy and the National Parachute Jumpers Association. He championed aviation to the very end of his life, loving the opportunities it had given him and wishing to enable those experiences for others.

Footnotes

- Popular Mechanics, ‘Are Flyers Born or Made?’ Vol. 53, No. 1, (Hearst Magazines, Jan 1930), pp.29.

- Eric Wind, ‘A Longines Lindbergh Actually Gifted By Lindbergh: The Zenith of Aviation Horology,’Hodinkee, (Hodinkee, APRIL 28, 2011), https://www.hodinkee.com/articles/a-longines-lindbergh-actually-gifted-by-lindbergh-the-zenith (date accessed: 22/08/16).

- Special to The New York Times, ‘Ready for Bermuda Hop,’ The New York Times, (The New York Times, June 29 1930). http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9C06E7DF1731E13ABC4151DFB066838B629EDE&legacy=true# (date accessed 22/08/16).

- Tom Pettey, ‘FLIES NONSTOP N.Y TO BERMUDA AND BACK, 17 HRS.’ Chicago Daily Tribune, (Chicago Tribune, June 30, 1930), pp. 3.

- Tom Pettey, ‘FLIES NONSTOP N.Y TO BERMUDA AND BACK, 17 HRS.’ Chicago Daily Tribune, (Chicago Tribune, June 30, 1930), pp. 3.

- Aviation history First Flight To Bermuda, https://www.historynet.com/aviation-history-first-flight-to-bermuda/ (date accessed 28/2/2022)

- Aviation history First Flight to Bermuda, https://www.historynet.com/aviation-history-first-flight-to-bermuda/ (date accessed 28/2/2022)

- Richard Martin, ‘Aviation’s Apostle,’ Popular Aviation, (Bonnier Corporation, October 1940), pp. 37.

- Richard Martin, ‘Aviation’s Apostle,’ Popular Aviation, (Bonnier Corporation, October 1940), pp. 37.

Bibliography

Anonymous, ‘Are Flyers Born or Made?’ Vol. 53, No. 1, Popular Mechanics, (Hearst Magazines, Jan 1930).

Anonymous, ‘Ready for Bermuda Hop,’ The New York Times, (The New York Times, June 29 1930). http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9C06E7DF1731E13ABC4151DFB066838B629EDE&legacy=true#

Martin, Richard. ‘Aviation’s Apostle,’ Popular Aviation, (Bonnier Corporation, October 1940).

Pettey, Tom. ‘FLIES NONSTOP N.Y TO BERMUDA AND BACK, 17 HRS.’ Chicago Daily Tribune, (Chicago Tribune, June 30, 1930).

Wind, Eric. ‘A Longines Lindbergh Actually Gifted By Lindbergh: The Zenith of Aviation Horology’, Hodinkee, (Hodinkee, APRIL 28, 2011), https://www.hodinkee.com/articles/a-longines-lindbergh-actually-gifted-by-lindbergh-the-zenith