While characters like Lindbergh, Douglas Corrigan and Richard E. Byrd were trailblazing the skies, pioneers such as Philip Van Horn Weems crafted instruments and navigational charts that would guide their success. Weems, often referred to as The Grand Old Man of Navigation revolutionised air travel throughout his career; time and time again he refined and mastered various techniques so that the heroes of this Golden Age could test the limits of air travel.

It is well known, that the men and women who work tirelessly behind the scenes of humanities great and daring feats, tend to be forgotten. Without Weems many of these celebrated famous flights would have ended in disaster, commercial flight and modern GPS as we know it may not have existed, and aviators would find themselves struggling with huge maps and lengthy algorithms wholly unfit for purpose.

Weems was one of the most incredible characters, the king and queen of the chess set, and most responsible for the development and conquering the challenges of air navigation.

Early Life

Born March 29th, 1889 in Tennessee, America, Weems and his seven siblings were orphaned in their youth as children. The family continued to work and provide for one another, and Weems went on to join the United States Naval Academy of Annapolis in 1908. He graduated in 1912 with an aptitude for navigation and went on to teach this subject at the Academy.

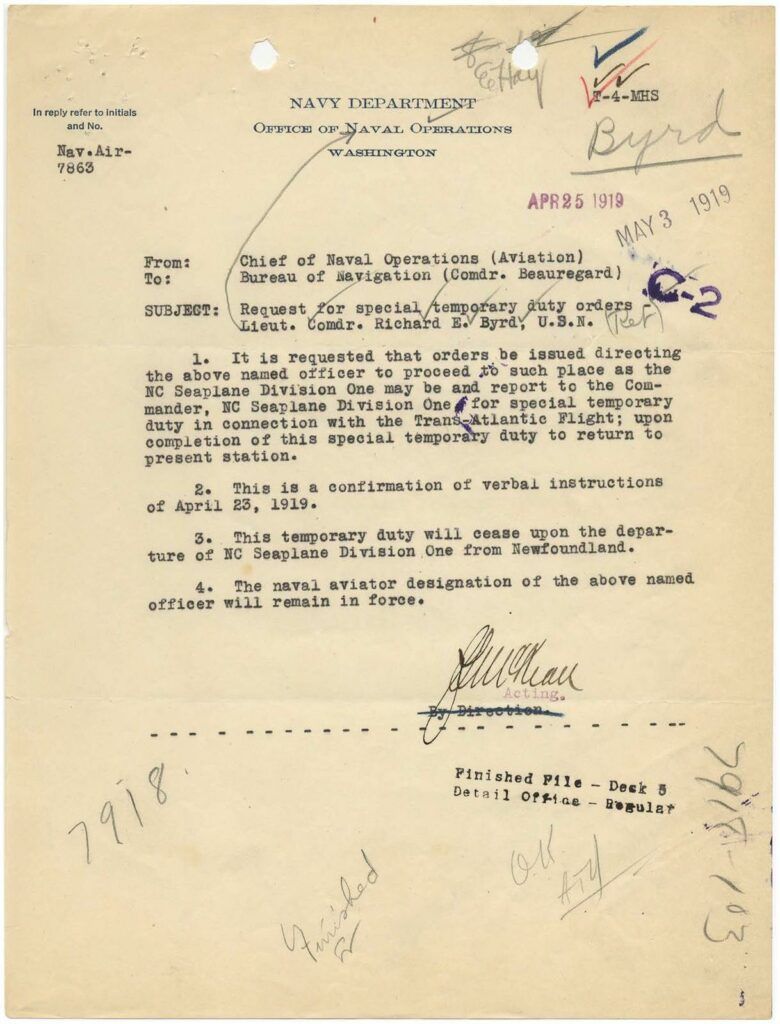

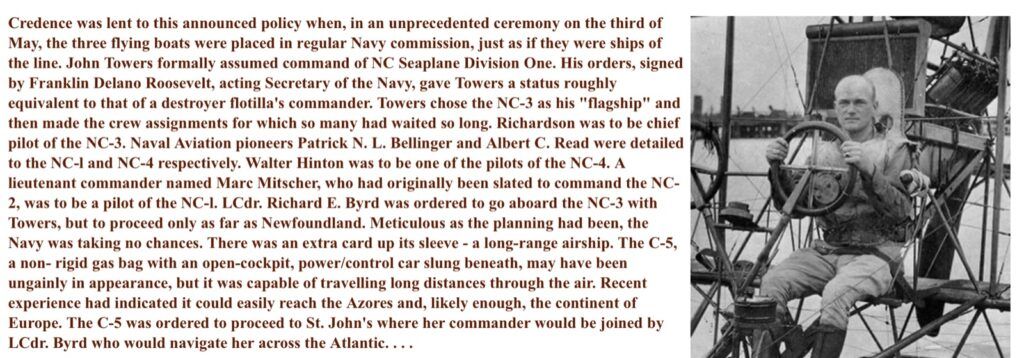

Eight years before Lindbergh’s famous and incredible solo flight Weems looked up at three small planes from his station tracking ship and wondered upon aerial navigation. The crew of the destroyer USS O’Brien, flew the transatlantic route from May 16th to the 27th of May, 1919. The NC-4 Curtiss Flying boat was guided by a fleet of 20 ships at 50 mile intervals along the route. Weems was stationed on a ship below, guiding the aircraft through treacherous waters.

Of the three planes that left Newfoundland only one made it to London. This first transatlantic flight was marred with tragedy and twenty-five hundred feet below Weems figured that there must be a simpler and safer solution to aerial navigation. To navigate a plane with sight alone was a near impossible task with the ever looming threat of fog and cloud cover. The huge fleet used to guide the planes also seemed thoroughly impractical.

Sailors had used methods that were relatively unchanged through the centuries, old and dated, the last major changes having been implemented in the early 19th century. The Harrison chronometer emerged in 1770, and shortly afterwards followed the Sumner technique of plotting celestial position lines came into play during the early 19th century.

This is how it had been for nearly a century until the 1930’s; Weems was the catalyst of these changes, pushing away the lengthy and impractical, attempting to try and test other means, all in the name of speed and efficiency ever crucial to aerial navigation. Alongside inventing new and revolutionary technology, his new techniques and methods became essential to navigation of the air.

To repeat the same methods in an aircraft was a veritable nightmare. ‘While ships didn’t rely on landmarks, but on complicated calculations based upon celestial bodies, air crews could not spend the time working out difficult computations. Even then, in the early days of navigation, planes just went too fast.’[1]

Weems continued to develop these ideas throughout his teaching days. From 1924 to 1927 he taught navigation at the Naval Academy, all the while thinking upon the advent of flight and the challenges therein. He went on to develop the Weems System of Navigation using the same marine calculations organized in a simplified way. These calculations were already computed and mapped out upon an easy to read table. This significantly aided speed and accuracy.

Large maps and complicated algorithms could be accommodated on a ship. Ships were significantly slower and more spacious than the cockpit of a plane. There was time to plot position, to anchor and wait for weather conditions to improve, to spread an array of maps and charts across a table.

Time was saved on solving lengthy calculations which, if inaccurate, could spell certain death. Weems published the Line of Position Book in 1927. While serving as executive officer on U.S.S. Cuyama (1928-1930) he wrote the acclaimed Air Navigation (1931), which was awarded a gold medal by the Aero Club of France.

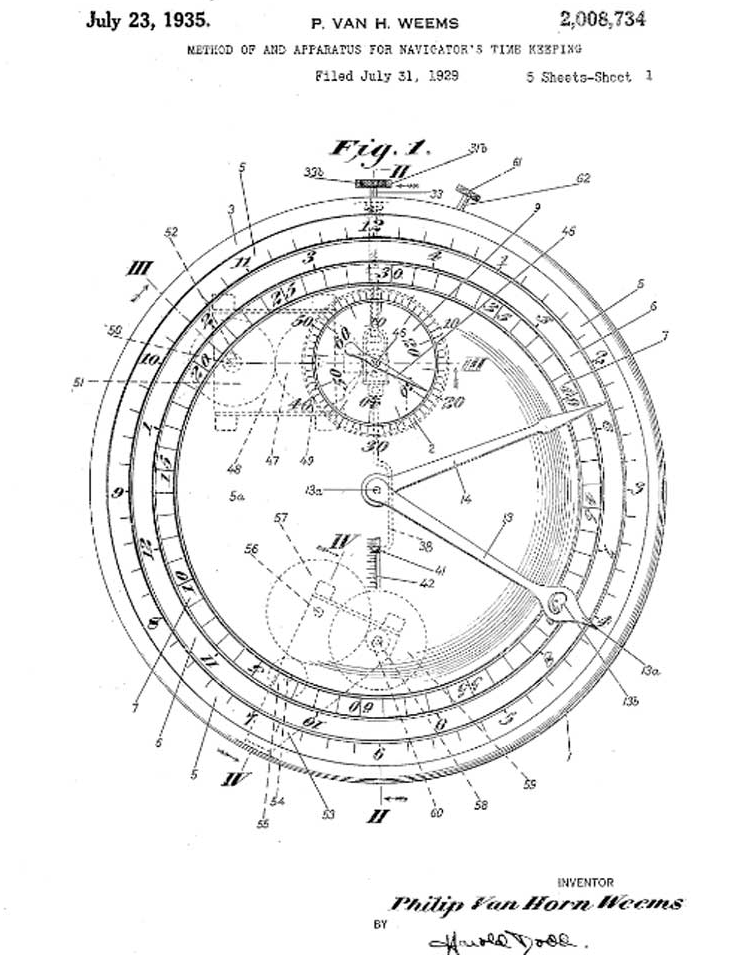

The Second Setting Watch

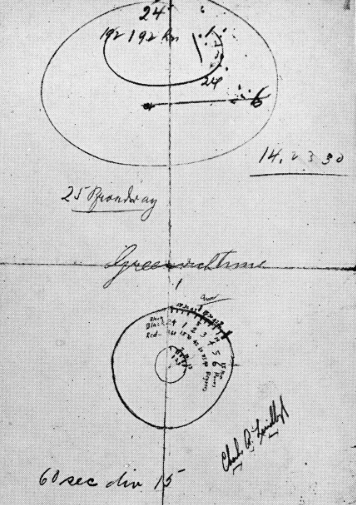

Weems designed the astonishingly accurate Second Setting Watch, enabling the aviators to determine Greenwich Mean Time down to the second. Understanding what that was- and is- was terribly important to celestial navigation. The watch quickly became an utter necessity to aviators at the time, and most were designed for the beautiful purpose of flight. ‘Given the turbulent cockpits and thick gloves needed for altitude flying, the Weems was typically oversized.

This 47mm watch’s distinguishing characteristic was its rotating center seconds dial. Pilots could listen to the minute beeps over the radio and adjust the dial, which maintained accuracy. The rotating inner dial displayed the correct minutes and graphically showed the margin of error from the original set time.’[2] The Second Setting Watch is largely regarded as the father of the Longines Hour-Angle watch as designed by Lindbergh.

Patent 2008734

His patent 2008734 describing a ‘method of and apparatus for navigator’s time keeping’, first filed in July 1929, took six years to approve. Weems held Avigation and Technical watch development roles at the new Longines-Wittnauer working alongside John Heinmuller. In 1936, he worked with the UK agent Baume submitting a list of technical improvements in the development of the so called “new second-setting watch”. A smaller Weems version with a turning bezel to make the second setting adjustment. The model would be ordered with different specs for both the US and UK militaries.

Weems went on to modify the sextant, that age old navigation essential, making it both faster and more reliable. Detractors often wondered why Weems would want to improve upon the old methods, tried and tested throughout the maritime years. This was a time where little government interest or money was offered to aviation.

The pioneers of this Golden Age knew that aviation was here to stay and foresaw the impact it would make on both commercial travel and national defense. Weems understood that the old ways would no longer serve an air borne future.

Weems generously shared his teachings with all who cared to learn. In 1927 he and his wife opened the Weems School of Navigation. Here, ‘he perfected his air navigation system by simplifying the method of determining latitude and longitude by aerial observations, improving sextants, and adapting chronometers to air use.’[3] As well as improving instruments and technique this school attracted the A-list of aviation’s Golden Age.

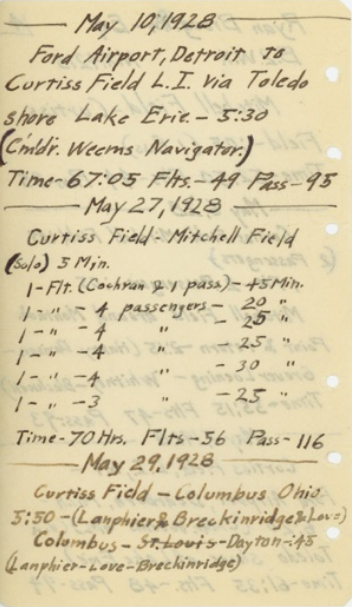

He taught navigation to Charles Lindbergh and his wife Anne Lindbergh. They would use his techniques throughout a number of successful flights. Weems first met Lindy in 1926 on an airfield in California and remarked: “Colonel Lindbergh, I would like to show you my sextant and watch.”[4] Lindbergh inspected these instruments and replied “Commander, I am very much interested in this; I would like to get together with you on it.”[5]

After Lindbergh’s incredible 1927 solo, nonstop, transatlantic flight Weems didn’t expect to hear back from him. He had rocketed into the spotlight and was inundated with requests and offers from movie and book deals, to new instruments, endorsements and planes. However after this flight, Lindbergh grew concerned over his lack of knowledge surrounding navigation. John P.V. Heinmuller writes:

Lindbergh Goes to School with Weems

Few persons know how deeply Lindy felt the need of improved navigation for safe flying, after he returned from his solo flight to Paris. He at once began a serious study of the subject with Commander P.V.H. Weems, determined to improve his technique, and later Mrs. Lindbergh joined him in the study.

Today they use all four known methods: (1) pilotage, (2) dead reckoning, (3) celestial navigation, and (4) radio navigation.

Through these new researches Lindbergh has become one of the foremost aerial navigators of our day, and I am sure flying will benefit immensely as a result, and fliers of future years will owe him much. He has invented a number of his own instruments, and has devised many short cuts for computing the Greenwich Hour Angle.[6]

Shortly after their first meeting Colonel Lindbergh had returned to learn the techniques that would lead to many future successful flights. Lindy and wife, Anne, went on to use Weems system to set a new transcontinental speed record between Los Angeles and New York. On April 20th, 1930, they arrived in New York after 14 hours and 45 minutes of flight. Lindy was so impressed by Weems system that he advocated the method.

Frederick J. Noonan was another aviator who took lessons at Weems School of Navigation. Noonan went on to map and chart courses for the Pan Am fleet of Flying Clipper Ships from 1925 to 1936. ‘Noonan, using the Weems System, played an important role in permanently changing the world’s concept of time and space and opening up international air travel for the public.’[7]

“Wrong-Way” Corrigan, was humorously nicknamed for supposedly flying in the wrong direction whilst emulating Lindbergh’s historic transatlantic flight. After authorities turned down Noonan’s request to follow Lindbergh’s 1927 route, Weems and Noonan began to make secret preparations.

In 1938 Noonan left from New York and landed in Dublin, Ireland, 23 hours and 13 minutes later. The authorities, angered at this blatant misconduct, demanded an explanation. Noonan asserted “I flew the wrong way. My compass got stuck.”[8] This charming anecdote earned him fame and a ticker tape parade down Broadway, a book and a movie deal. None of which would have been possible without Weems expertise.

Collaboration with Harold Gatty

Harold Gatty was making waves in the aviation circuit and became renowned as an expert navigator. He and Weems collaborated together and Weems was so impressed that he asked Gatty to teach at the School of Navigation and Gatty taught avigation to commercial airlines and the US military. He went on to advise Lindbergh’s transcontinental flight in the new Lockheed Cirrus.

In 1930 the Lindbergh’s successfully crossed the continent in 14 hours and 45 minutes. Gatty played no small part in their success and was named the ‘Prince of Navigators’[9] by Charles Lindbergh himself. Gatty prepared Weems curves and maps for the extraordinary flight. Gatty went on to find fame in one of the most incredible flights of this Golden Age.

In 1931 Gatty navigated the infamous Winnie Mae with, one eyed pilot, Wiley Post in the very first round-the-world flight. He also served as chief advisor to Howard Hughes whirlwind round-the-world flight of 1938.

Both Admiral Byrd and Hubert Wilkins were instructed by Weems before their various daring Polar expeditions. In the early 1930’s Admiral Richard E. Byrd invited Weems to the South Pole. He was of course keen to have an expert on board. Weems had to decline due to his own business commitments. He simply could not dedicate two years to Byrd’s Antarctic adventure.

Col. Charles Blair sought him out for instruction in celestial navigation. Blair was preparing for his flight over the North Pole. Weems settled on a totally pre-computed solution for Blair, which involved plotting his flight in advance, and working out the altitude of the sun for a number of points along the path.

These sun-altitudes were then joined to form a graph. In flight, all Blair had to do was to take a sight and compare his observation with the predicted altitude from the graph. The difference between the two values indicated how far he was off track or off schedule. Weems and Blair carried out the computations four times, in case Blair had to delay his take-off by a day and also to allow for having to delay the hour of take-off from noon to one o’clock.[10]

Blair found this method incredibly easy to use, hardly having to plot and devoid of cumbersome maps, he touched down at Point Barrow one minute ahead of schedule.

Weems continues to Influence

Weems influence and impact upon these early pioneers and extraordinary flights cannot be underestimated. His legacy is far reaching and un-quantifiable. He guided the explorers of his time as well as those to come. He inspired navigators and inventors alike who would go on to develop and learn from his methods and his unyielding quest to perfect these techniques.

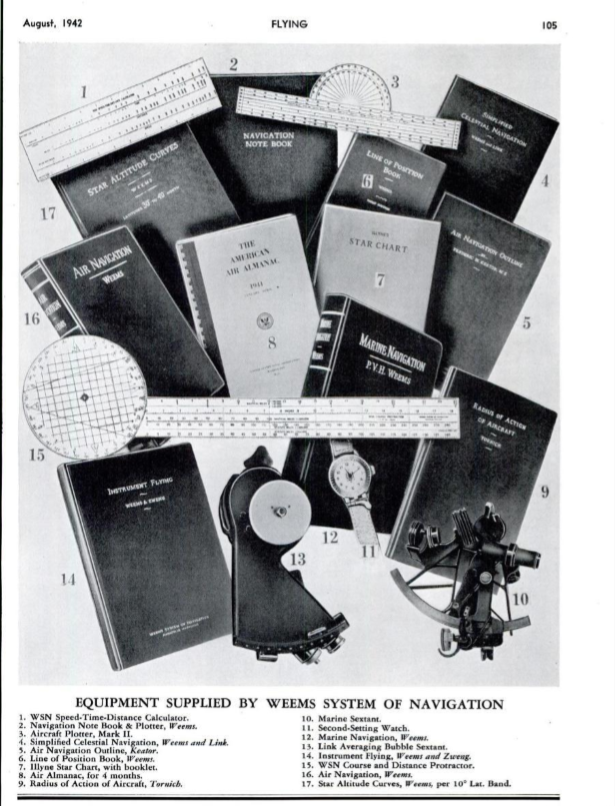

In a bid to concentrate solely on developing navigation methods, Weems opted onto the naval retired list in 1933. All of his energies were now devoted to further perfecting his system. Within a year he designed the first Air Almanac and two years later he designed the Mark II Plotter. He also published both Marine Navigation and Star Altitude Curves.

Weems Star Altitude Curves, offered a simplified method of finding one’s position. This technique was crucial to the Army Air Corps who adopted it shortly before World War II. The tide had changed and both public and private interest in aviation soared. Weems, alongside his wife, began to market his system.

Despite retiring from the Navy, Weems was continually called back to active duty to advise upon navigation and provide tutelage. He returned to the Navy in 1942 to aid in the war effort and was awarded a Bronze Star for his service as a convoy commander.

In light of this, alongside his continuous contributions to navigation, Weems was promoted to the rank of Captain and received the Wings of Naval Air Navigator in 1945. He, once again, retired from active duty in 1946 in order to continue his private career in navigation.

In 1948 Weems flew to the North Pole in a journey that was both rare and extraordinary. He also flew around the world in 1950. Throughout each journey he kept a detailed log with extensive notes in order to further his navigation studies. He led both flights, with skill and precision, to their destination and safe return.

At 71 years of age he was called back to the Navy in order to teach four young ensigns about space navigation. This was the last time that Weems would be called back to active duty; asked to devise an instrument which would allow astronauts to find their way without computers.

His legacy has reached from sky to space allowing adventurers and explorers alike to reach ever further toward the heavens. He heavily influenced air navigation programs of U.S. airlines and the military, shaping modern commercial flight and military defense. His navigation methods would be utilized as the standard for long-range navigation for three decades.

Weems was awarded the Magellanic Premium in 1953. This honor is awarded for contributions to navigation, astronomy or natural philosophy. It has only been awarded 33 times to 40 people since its establishment in 1786. Weems was awarded a gold medal from the American Institute of Navigation in 1960.

This prestigious award recognized fifty years of outstanding accomplishment in air navigation. The National Geographic Society awarded him the John Oliver la Gorce Medal in 1968 and Mount Weems in Antarctica is named in his honor.

Weems’ company still exists today in the form of Weems and Plath, ‘producing a full spectrum of precision marine instruments for pleasure boaters, commercial vessels, cruisers, serious yacht racers, and the military. These include brass nautical clocks and barometers, navigation tools, high-end oil lamps, Imray books and charts, binoculars, children’s books, and more.’[11] Production is still based in Weems home of Annapolis, not far away from his beloved Naval Academy.

His home in Annapolis would always hold a special place in his heart. He spent many years testing new techniques from his front porch. His house was 38 degrees 58.8 minutes North latitude, 76 degrees 29.4 minutes West longitude, known to Weems in order to observe the sun and stars with a marine or bubble sextant. He kept a log for many years, detailing the observations of intrigued visitors interested in the art of navigation.

Weems died at the age of 90 on June 2nd, 1979 in Annapolis. The Maritime Institute of Technology honored him with their exhibition “Before GPS: the Genius of Captain Philip Van Horn Weems, 20th Century Navigation Pioneer.” This exhibition looked back upon his contributions to aviation and the impossible feats Weems made possible.

‘Alexander von Humboldt[…] observed that there are three stages in scientific discovery: first people deny that it is true; then they deny that it is important; finally they credit the wrong person.’[12]The origination of the Global Positioning System (GPS) is still in dispute. However, there are few who can deny Weems impact and influence upon modern GPS. We’ve certainly come a long way from the sailors who travelled the seas with nothing more than the sun, the stars and bravado to guide their vessels.

N.W. Emmot, writes for The Institute of Navigation, remarking that,

Other people may be impressed by Weems’ accomplishments, but Weems himself was not. He was at all times completely approachable, polite and pleasant. Letters to him were always answered promptly, and sometimes in his own handwriting. Those who met him always found him a thorough gentleman.

Captain Weems died June 2, 1979 at the age of ninety and will always be remembered as one of the great navigators of the Twentieth Century. In memory and in honor of Weem’s significant contributions to navigation, The Institute of Navigation created an award given annually to an outstanding individual “For Continuing Contributions to the Art and Science of Navigation.”[13]

Footnotes

- Joseph Patrick Bulko, ‘The Story of Weems & Plath,’ Glimpses into the life of Captain Philip Van Horne Weems, http://www.weemsjohn.com/TheGrandoldManofNavigation.html (date accessed: 29/09/16).

- Max E. Reddick, ‘The History of the Pilot Watch Part Four: Longines and Lindbergh,’ MONOCHROME, (2006 – 2015 Monochrome, 04/01/13), https://monochrome-watches.com/the-history-of-the-pilot-watch-part-four-longines-and-lindbergh/(date accessed: 29/09/16).

- N. W. Emmot, ‘P.V.H. Weems 1889-1979,’ Glimpses into the life of Captain Philip Van Horne Weems, http://www.weemsjohn.com/TheGrandoldManofNavigation.html (date accessed: 29/09/16).

- P.V.H Weems, ‘The Adventurers,’ Glimpses into the life of Captain Philip Van Horne Weems, http://www.weemsjohn.com/TheGrandoldManofNavigation.html (date accessed: 29/09/16).

- Charles A. Lindbergh, ‘The Adventurers,’ Glimpses into the life of Captain Philip Van Horne Weems, http://www.weemsjohn.com/TheGrandoldManofNavigation.html (date accessed: 29/09/16).

- John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘IV Charles Augustus Lindbergh,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. 75.

- N. W. Emmot, ‘The Adventurers,’ Glimpses into the life of Captain Philip Van Horne Weems, http://www.weemsjohn.com/TheGrandoldManofNavigation.html (date accessed: 29/09/16).

- Douglas Corrigan, ‘The Adventurers,’ Glimpses into the life of Captain Philip Van Horne Weems, http://www.weemsjohn.com/TheGrandoldManofNavigation.html (date accessed: 29/09/16).

- Terry Gwynn-Jones, ‘Harold Gatty: Aerial Navigation Expert,’ Aviation History Magazine, (World History Group, September 2001), http://www.historynet.com/harold-gatty-aerial-navigation-expert.htm (date accessed: 19/08/16).

- N. W. Emmot, ‘THE GRAND OLD MAN OF NAVIGATION,’ Glimpses into the life of Captain Philip Van Horne Weems, http://www.weemsjohn.com/TheGrandoldManofNavigation.html (date accessed: 29/09/16).

- Joseph Patrick Bulko, ‘The Story of Weems & Plath,’ Glimpses into the life of Captain Philip Van Horne Weems, http://www.weemsjohn.com/TheGrandoldManofNavigation.html (date accessed: 29/09/16).

- Alexander von Humboldt as quoted by Bill Bryson, A Short History of Nearly Everything, (Broadway Books, September 14th 2004), pp. 180.

- N.W. Emmot, ‘Capt. P.V.H. Weems The Grand Old Man of Navigation Part 2,’ The Institute of Navigation Newsletter, Volume 16, Number 3, (Ion, Fall 2006), pp.7.

Bibliography

Emmot, N. W. ‘The Adventurers,’ Glimpses into the life of Captain Philip Van Horne Weems, http://www.weemsjohn.com/TheGrandoldManofNavigation.html

Emmot, N.W. ‘Capt. P.V.H. Weems The Grand Old Man of Navigation Part 2,’ The Institute of Navigation Newsletter, Volume 16, Number 3, (Ion, Fall 2006).

Emmot, N. W. ‘P.V.H. Weems 1889-1979,’ Glimpses into the life of Captain Philip Van Horne Weems, http://www.weemsjohn.com/TheGrandoldManofNavigation.html

Gwynn-Jones, Terry, ‘Harold Gatty: Aerial Navigation Expert,’ Aviation History Magazine, (World History Group, September 2001), http://www.historynet.com/harold-gatty-aerial-navigation-expert.htm

Heinmuller, John P.V. ‘IV Charles Augustus Lindbergh,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945).

Humboldt, Alexander von. as quoted by Bryson, Bill. A Short History of Nearly Everything, (Broadway Books, September 14th 2004).

Patrick Bulko, Joseph. ‘The Story of Weems & Plath,’ Glimpses into the life of Captain Philip Van Horne Weems, http://www.weemsjohn.com/TheGrandoldManofNavigation.html

Reddick, Max E. ‘The History of the Pilot Watch Part Four: Longines and Lindbergh,’ MONOCHROME, (2006 – 2015 Monochrome, 04/01/13), https://monochrome-watches.com/the-history-of-the-pilot-watch-part-four-longines-and-lindbergh/