James Allan Mollison the flying Scotsman was born on the 19th of April, 1905 in Lanarkshire, Scotland. Dubbed the Flying Scotsman in his 1996 book, Mollison the Flying Scotsman, by David Luff, Mollison was a colorful character throughout his life. Perhaps best known as the daredevil Scot who survived a vast number of near misses. ‘His career was marked by unusual success in small planes, in long flights requiring great stamina and courage.’[1] Mollison was undoubtedly a valued member of the Longines Honor Roll.

Pushing the Limits

He would often push himself to the upmost limit in long distance solo flights before his energy would give way and a haphazard landing would follow. This in no way diminishes his extraordinary skill as a pilot, navigator and trained mechanic. Throughout his career he broke a number of impressive records, always pushing himself further to achieve ever more.

Passionate about flying from an early age, Mollison learned to fly in his teens. He obtained his Royal Air Force (RAF) Short Service Commission at 18, being the youngest officer in the service. This was to be the first in a long line of record breaking triumphs by Mollison.

Mollison served in India early in his RAF career in the Wazaristan Campaign in 1925. where he was awarded an India General Service Medal. That a young man from Scotland should distinguish himself so early in his career is a mark of the man he would become.

From India he moved to Australia where he worked as a bathing beach attendant, until the pull of aviation drew him back again.

Daily Flights Melbourne to Sydney

He went on to assume the role of pilot with Eyre Peninsular Airways and Australian National Airways. Flying from Melbourne to Sydney daily by seat of the pants flying with his co-pilot Sir Charles Kingsford Smith.

At 22 he went on to become the youngest flying instructor at Central Flying School (CFS). From 1928–29, he served with the South Australian Aero Club in Adelaide as a flight instructor. His career as an instructor was almost cut short when he was told that he could no longer teach due to his lack of a “B” license. He solved this problem by journeying to Melbourne and convincing the authorities to award him the license without having to take the required tests.

His career in aviation was well underway at an astonishingly young age. Throughout these formative years he gained vital experience in navigation, aviation and mechanics which would stand him in good stead for future record breaking attempts. By 1931 he was an incredibly skilled pilot, entering the world aviation stage with his first famous flight.

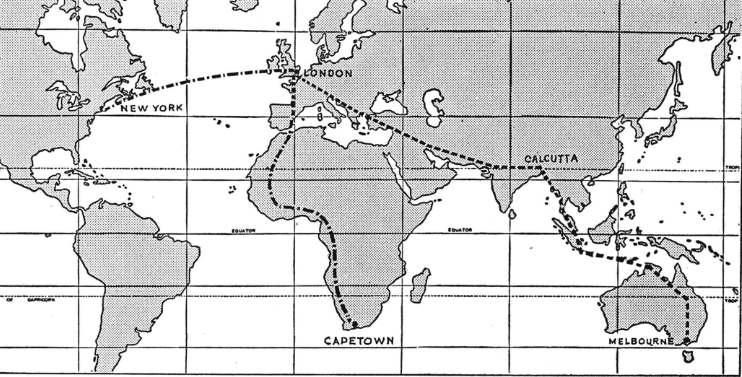

On July 1st 1931, Mollison flew from Australia to England in just 8 days and 19 hours. In 1932, further securing his name as one of aviation’s greats, he flew from England to South Africa in 4 days and 17 hours. The publicity that followed helped the Scot to make a name for himself, which was as crucial as skill, in the early days of air-borne daredevils.

Married to Amy Johnson

Tabloids and public alike obsess over romance, courage and danger. Jim Mollison went on to marry famed aviator Amy Johnson in July 1932. A whirlwind romance, he proposed to her, mid-flight, only 8 hours after making her acquaintance during one of his commercial flights with Australian National Airways. The press dubbed them The Flying Sweethearts as they went on to garner international fame, flying both alone and together.

Jim had set the England to South Africa record in March 1932, with a time of 4 days and 17 hours. There was no small amount of competitiveness between Amy and Jim who were often trying for the same records. Shortly after they married in 1932 Amy set off to break her husband’s England to South Africa record. She beat his time by 10 and a half hours.

Mollison broke yet another record on August 18 1932, as the first pilot to travel solo on an East-to-West, trans-Atlantic hop from Portmarnock in Ireland to Pennfield, New Brunswick, Canada. In February 1933 Mollison flew from England to Brazil in 3 days and 13 hours in record time. This journey would also mark the very first solo crossing of this kind.

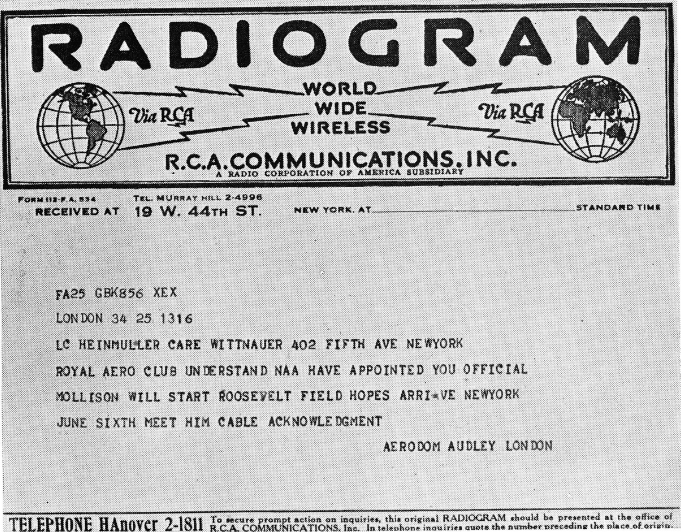

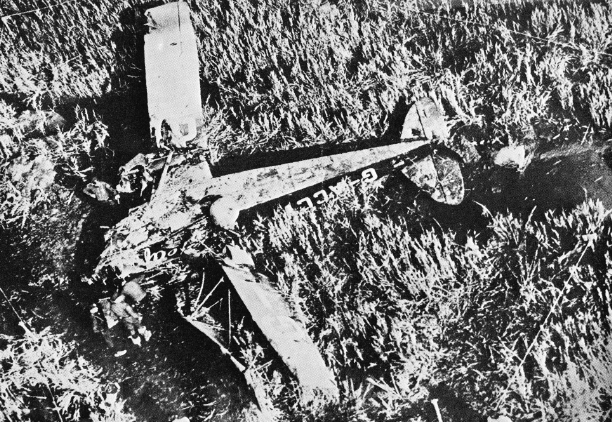

In 1933 he and his wife survived a pretty serious crash as they traveled the Atlantic, Westward, on route to New York. The twin-engine De Havilland was smashed irreparably as the plane nose-dived upon landing. They were attempting their first recording breaking flight across the world and just missed their target after running out of fuel in Connecticut.

The couple took part in the 1934 MacRoberston Air Race but were forced down at Allahabad after damaging the engines of their De Havilland DH.88 Comet with improper fuel. Going for the same records, moving in the same circles and sharing such an intense passion for aviation was the end of them. The marriage became strained and The Flying Sweethearts divorced in 1938.

World War II and Beyond

During WWII Mollison served in the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA) and was eventually made a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) for his contribution to the War effort. After the War, Mollison struggled with alcoholism. This had been somewhat of a vice throughout his life, reportedly causing problems within his marriage to Amy Johnson.

It is often taken for granted that these early aviators, who risked life and limb to pursue advances in flight, did so with an unshakable and unfaltering courage. After witnessing so many of their fellow friends and colleagues die and disappear it is understandable that the sort of immortal characters presented in the media were anything but.

Newspapers of the time routinely wrote obituaries of pilots before each air race in preparation for their death. Roscoe Turner, known for his daring pursuit of speed, remembers being sent his own obituary the night before the 1935 Cleveland race. On this matter he stated: “No matter how many newspapers turn you into a superman, an immortal, you’re still a man inside, you don’t quite feel like dying, and you’re generally scared as hell.”[2]

Perhaps a drink to calm the nerves for Mollison became a vice that took hold of his life. His ex-wife Amy died in an ATA accident during WWII and it is true that the casualty rates were high. During WWII, ‘55,573 were killed out of a total of 125,000 aircrew (a 44.4 percent death rate), a further 8,403 were wounded in action, and 9,838 became prisoners of war.’[3] The skies at this time, were not the safest place to be.

Mollison died on the 30th of October 1959, aged 54. His drinking had become ever more serious and his pilot’s license had been revoked in 1953. He ran a public house in London with his second wife, Maria Clasina E Kamphuis, but they later separated. At the end of his life he could be found running the Carisbrooke Hotel in Surbiton.

A somewhat tragic end to a daring and adventurous life. Mollison, the Scot from Lanarkshire, had taken center stage on the international aviation circuit. He had been the first man to fly both the North and South Atlantic and had shown both stamina and courage throughout each grueling long distance flight. He was one of the most skilled navigators, mechanics and pilots of his time who contributed to aviation in the records he broke and the boundaries he pushed.

Footnotes

- John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘XIII James Allan Mollison and Amy Johnson Mollison’, Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), 184.

- The National Aviation Hall of Fame, ‘Turner, Roscoe,’ NAHF, http://www.nationalaviation.org/our-enshrinees/turner-roscoe/ (date accessed: 30/08/16).

- Wikipedia, ‘RAF Bomber Command,’ Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RAF_Bomber_Command (date accessed: 31/08/16).

Bibliography

Heinmuller, John P.V. ‘XIII James Allan Mollison and Amy Johnson Mollison’, Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945)

The National Aviation Hall of Fame, ‘Turner, Roscoe,’ NAHF, http://www.nationalaviation.org/our-enshrinees/turner-roscoe/

Wikipedia, ‘RAF Bomber Command,’ Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RAF_Bomber_Command