A member of the Longines Honor Roll, James Erroll Dunsford Boyd, commonly known as ‘The Lindbergh of Canada,’[1] became the first Canadian to fly the Atlantic.

Often flying blind throughout this dark and treacherous journey, Boyd proved himself to be an exceptionally skilled pilot.

Adventurous and daring, Boyd was also described as a dreamer; a romantic who reached above and beyond the confines of his earthbound existence, destined for the skies.

His character, as such, is recounted by a London newspaper columnist after dinner with Boyd, Harry P. Connor, and Colonel J.T.C. Moore-Brabazon:

…the Canadian, Captain Boyd, thirty-nine years old, stout and good-natured, but a romantic, and the American, Lieutenant Connor, a scientific fanatic in regard to all forms of navigation. To Lieutenant Connor the Atlantic crossing means simply a test for his instruments–and nothing more. And death would imply nothing but a failure of those instruments. Here, nevertheless, as in other walks of life, the materialist is dominated by the romantic. It is Captain Boyd who provides the driving force of the partnership.[2]

Flying the Maple Leaf

Owing to his romantic demeanor, Boyd gained some recognition as a songwriter after WWI with the Broadway hit, ‘Dreams.’ He certainly encapsulated this in his ambitious desires that could not be grounded by misfortune or financial setbacks. His first Atlantic crossing in the newly christened Maple Leaf stands testament to these attributes.

Boyd took the Wright-Bellanca WB-2 aircraft, Columbia, to Toronto. She was appropriately renamed Maple Leaf in honor of his Canadian heritage before being grounded for a tedious three weeks at the Hubert Airport in Montreal.

Mounted Police had ordered them to land the aircraft over a dispute between Roger Q. Williams and, owner of the Bellanca, Charles A. Levine.

As the weeks drew in, winter was fast approaching. Connor, increasingly concerned over the late departure of Boyd’s flight, sent numerous letters begging him not to fly solo as he had intended. For Connor, it was simply too dangerous.

Boyd conceded, seeing sense in his navigator’s pleas, and invited him aboard the Maple Leaf to complete the journey together. Connor brought a new Sperry artificial-horizon indicator along for the ride and shortly after his arrival the Maple Leaf was released into Boyd’s custody.

Upon reaching Harbour Grace, Newfoundland, Boyd had to contend with continual reports of unfavorable weather and an airstrip that had destroyed a Lockheed Vega just two months prior. Determined not to repeat the performance of Captain John Henry Mears and his pilot, Harry Brown, Boyd made meticulous preparations before take-off.

Weather reports continually urged Boyd to rethink his departure, to delay until more favorable conditions prevailed. Knowing that this would likely mean a delay lasting into the summer months Boyd decided to depart into less than perfect skies, with the heavily loaded Maple Leaf on October 9th.

Another setback emerged as Boyd and Connor met with a heavy fog that delayed the flight until the afternoon. Boyd later recalled:

I had hoped for an earlier start, giving us the opportunity of using up at least 100 gallons of fuel before darkness, which would have lightened the plane some 600 pounds, making flying much easier during the long, dark hours ahead of us.

With a heavy load, the Bellanca tends to hunt and fall off on either wing, which would probably have sent the ship spinning into the Atlantic.[3]

He attempted to pull the weighty plane into the air. She would not budge. Laden with fuel, the Maple Leaf stuck to the runway; her tail skid sinking into the ground and acting as an unwanted anchor.

A Little Push Please

Boyd encouraged onlookers to push the plane and the aircraft began to slowly roll along the airstrip. Boyd remembers this nervous takeoff,

‘After warming up the engine we buckled our belts and were ready for what I considered the most hazardous part of the flight – the first few moments which could mean the difference between life and death.’[4]

The rest of the flight was not without difficulty. They encountered icy conditions and stormy weather in the middle of the ocean.

Without the reliable engine, cabin pressurization technology, and de-icing equipment of today’s modern planes the journey posed a number of risks.

The weather forced them to take a considerable detour. They also had to change altitude to lessen the chance of ice fractured wings:

Boyd had painted a black stripe on the wing’s leading edge and, with the aid of a flashlight, could see white particles of ice rapidly forming on the wing. He immediately descended and followed a southerly heading for some time, abandoning their planned track.

Once they reached warmer temperatures, he climbed again into the clouds on an east-northeasterly course, calculated by dead reckoning.[5]

Boyd and Connor carried no radio, to save weight, and vibrations upon take-off had rendered the earth-inductor compass dial un-serviceable.

Dead Reckoning

They relied solely on two magnetic compasses and dead reckoning to guide them through a journey that was mostly pitch black.

At one stage the electrics failed and flashlights were used to power the phosphoric material on the flight instruments. Boyd ‘felt as though [he] was piloting a car in a coal mine.’[6]

Boyd was relieved to see dawn after a night that lasted 10 and a half hours. They soon discovered a serious issue with their 100 gallons of fuel in the main reserve tank. The line was clogged, turning the fuel into deadweight.

It was a problem they could not remedy in the air. Aided by very strong south-westerly winds they made it to the Scilly Isles. The landing was no small feat:

Boyd set the machine down on a sloping beach between two streams at Tresco, stopping within a few inches of the water, only 200 feet from where the landing gear first touched the soft sand.

The fuel tanks were almost empty. Connor later remarked that he had not thought anyone could land on that narrow strip.[7]

Arrival in London

The Maple Leaf departed the next day, arriving at London’s Croydon Airport three hours later.

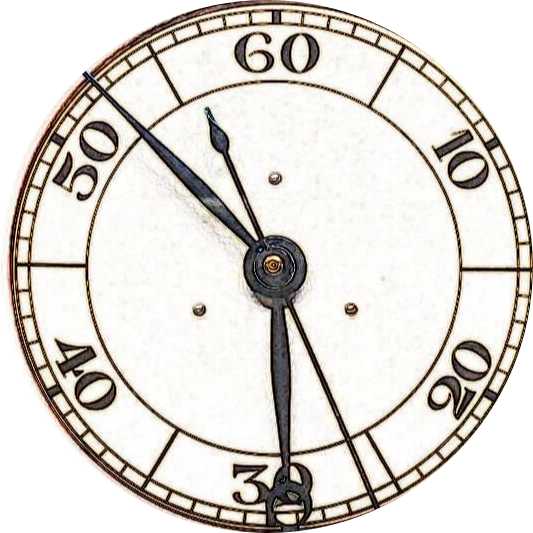

They emerged after a 2,200-mile journey, in 23 hours and 44 minutes, dressed in ordinary business clothes in order to demonstrate the routine nature of the flight.

The pioneer Boyd wished to indicate that ‘year-round transatlantic air service was feasible.’[8] This seminal flight would see him crowned ‘The Lindbergh of Canada.’[9]

This was not his first, nor his last, trailblazing journey. On June 29th, 1930, at the controls of the Wright-Bellanca WB-2 aircraft named Columbia, Boyd, Roger Q. Williams, and Harry P. Connor sought to ‘prove the feasibility of a regular passenger service between New York and Bermuda.’[10]

Their non-stop journey from New York to Bermuda and back had spectators placing 5-to-1 odds against their safe return.

Boyd was to emerge triumphant, 17 hours and 8 minutes later, against the predictions of detractors. After braving one of the ‘fiercest rain squalls [Williams had] ever saw’[11] just forty miles off their destination, they were relieved to have escaped a potentially fatal storm.

The plane itself had no radio or lifesaving equipment leaving no real room for error. Boyd, Conner, and Williams circled the tiny coral island without one landing from start to end despite a faltering engine and impossible visibility. Boyd recalls reaching Bermuda, Hamilton:

I was a little suspicious when Harry sent up a word to change course, stating we would arrive over Bermuda in ten minutes. At 2:23 we sighted the islands…Connor had a grin from ear to ear. This slim calculating naval officer had accomplished a navigational feat second to none.[12]

The crew flew over Bermuda below 200 feet and dropped the mail on the island, which offered no airport.

This journey inspired Pan American and British Imperial Airways to create courses from New York to Hamilton.

Previously inaccessible by air, regular commercial routes emerged just 7 years later. The duration of flights were cut dramatically at 4.5-5.5 hours for a one-way journey.

Without Boyd, Williams, and Connor these routes would never have been actualized; offering new opportunities to passengers and pilots alike.

They had completed their intended objective and had been the first to ‘prove the feasibility of a regular passenger service between New York and Bermuda.’[13]

Born on November 22nd, 1891, Boyd would go on to pioneer some of the finest flights in aviation history.

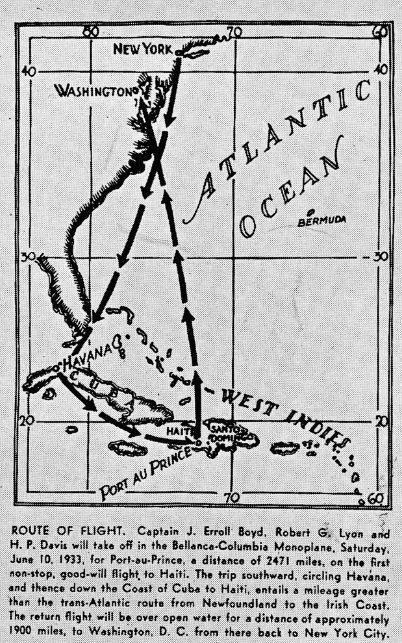

Less than three years after his Atlantic crossing, Boyd made the first nonstop flight from New York City to Haiti.

He was cheered off from New York by some 5,000 onlookers in 1933.

From this flight both Haiti and Canada commissioned special stamps.

He was the first aviator for which two countries had commissioned these honorary stamps.

J. Erroll Boyd literally paved the way for commercial aviation routes and traveled in conditions no one else dared.

He went on to write a popular column about aviation for the Toronto Star and the Miami Press.

He predicted developments in aviation that were years ahead of his time and was a dedicated ambassador for the development of efficient and safe air travel. His contributions to aviation are vast and innumerable.

Footnotes

[1] Ross Smyth, The Lindbergh of Canada: The Erroll Boyd Story, (GeneralStore PublishingHouse, 1997), pp.5.

[2] Ross Smyth, ‘Erroll Boyd: World War I Combat Pilot and Aviation Daredevil,’ Aviation History, (World History Group, November 2000), http://www.historynet.com/erroll-boyd-world-war-i-combat-pilot-and-aviation-daredevil.htm (date accessed: 23/08/16).

[3] Ross Smyth, ‘Erroll Boyd: World War I Combat Pilot and Aviation Daredevil,’ Aviation History, (World History Group, November 2000), http://www.historynet.com/erroll-boyd-world-war-i-combat-pilot-and-aviation-daredevil.htm (date accessed: 23/08/16).

[4] Ross Smyth, The Lindbergh of Canada: The Erroll Boyd Story, (GeneralStore PublishingHouse, 1997), pp. 8.

[5] Ross Smyth, ‘Erroll Boyd: World War I Combat Pilot and Aviation Daredevil,’ Aviation History, (World History Group, November 2000), http://www.historynet.com/erroll-boyd-world-war-i-combat-pilot-and-aviation-daredevil.htm (date accessed: 23/08/16).

[6] Ross Smyth, ‘Erroll Boyd: World War I Combat Pilot and Aviation Daredevil,’ Aviation History, (World History Group, November 2000), http://www.historynet.com/erroll-boyd-world-war-i-combat-pilot-and-aviation-daredevil.htm (date accessed: 23/08/16).

[7] Ross Smyth, ‘Erroll Boyd: World War I Combat Pilot and Aviation Daredevil,’ Aviation History, (World History Group, November 2000), http://www.historynet.com/erroll-boyd-world-war-i-combat-pilot-and-aviation-daredevil.htm (date accessed: 23/08/16).

[8] Ross Smyth, The Lindbergh of Canada: The Erroll Boyd Story, (GeneralStore PublishingHouse, 1997), pp. 2.

[9] Ross Smyth, The Lindbergh of Canada: The Erroll Boyd Story, (GeneralStore PublishingHouse, 1997), pp. 5.

[10] Tom Pettey, ‘FLIES NONSTOP N.Y TO BERMUDA AND BACK, 17 HRS.’ Chicago Daily Tribune, (Chicago Tribune, June 30, 1930), pp. 3.

[11] Tom Pettey, ‘FLIES NONSTOP N.Y TO BERMUDA AND BACK, 17 HRS.’ Chicago Daily Tribune, (Chicago Tribune, June 30, 1930), pp. 3.

[12] Ross Smyth, ‘Erroll Boyd: World War I Combat Pilot and Aviation Daredevil,’ Aviation History, (World History Group, November 2000), http://www.historynet.com/erroll-boyd-world-war-i-combat-pilot-and-aviation-daredevil.htm (date accessed: 23/08/16).

[13] Tom Pettey, ‘FLIES NONSTOP N.Y TO BERMUDA AND BACK, 17 HRS.’ Chicago Daily Tribune, (Chicago Tribune, June 30, 1930), pp. 3.

Bibliography

Pettey, Tom. ‘FLIES NONSTOP N.Y TO BERMUDA AND BACK, 17 HRS.’ Chicago Daily Tribune, (Chicago Tribune, June 30, 1930)

Smyth, Ross. ‘Erroll Boyd: World War I Combat Pilot and Aviation Daredevil,’ Aviation History, (World History Group, November 2000), http://www.historynet.com/erroll-boyd-world-war-i-combat-pilot-and-aviation-daredevil.htm

Smyth, Ross. The Lindbergh of Canada: The Erroll Boyd Story, (GeneralStore PublishingHouse, 1997)

I would like your permission to use excerpts from tghis article for a magazine story in Canadian Aviator.

Gary Hebbard

Greetings Gary… you would be most welcome to. If you can just credit flightbirds.net be much appreciated. Many thanks Andy 🙂