“Every vision is a joke until the first man accomplishes it; once realized, it becomes commonplace.” [1].

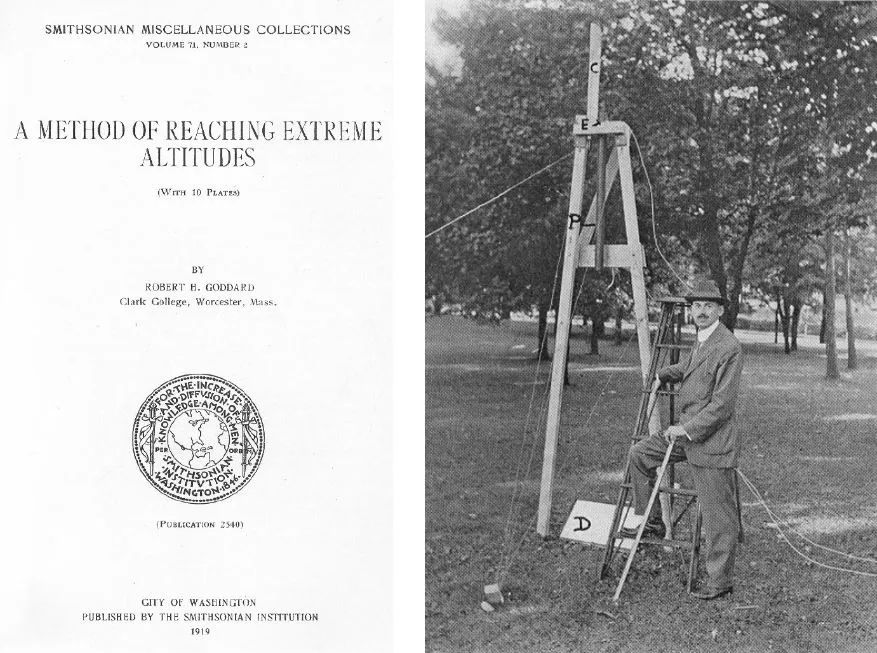

This was Robert Goddard’s response to a reporter post-1919 publication of his, “A Method for Reaching Extreme Altitudes,” in the Smithsonian’s miscellaneous collections.

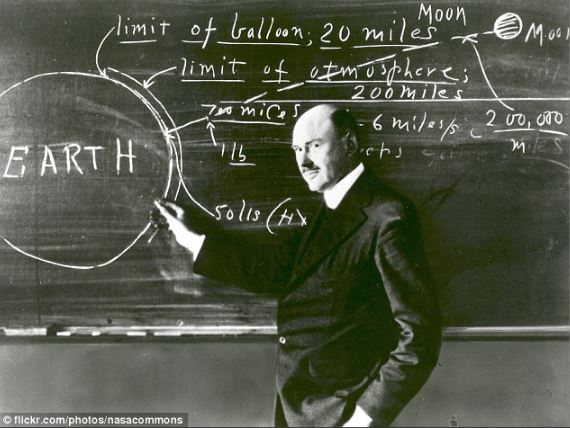

In his paper, Goddard detailed the technical aspects of liquid-fueled rockets, their potential to reach high altitudes, escape Earth’s atmosphere and their ability to be used for scientific and research applications like in the assessment of upper atmospheric conditions. He noted the behavior of materials in a vacuum and discussed rocket design, fuel types, and their guidance systems.

He stated, “It is possible to conceive of rocks being fired by explosives, not only to greater altitudes but to any desired distance horizontally.” [2]

The New York Times gets it wrong

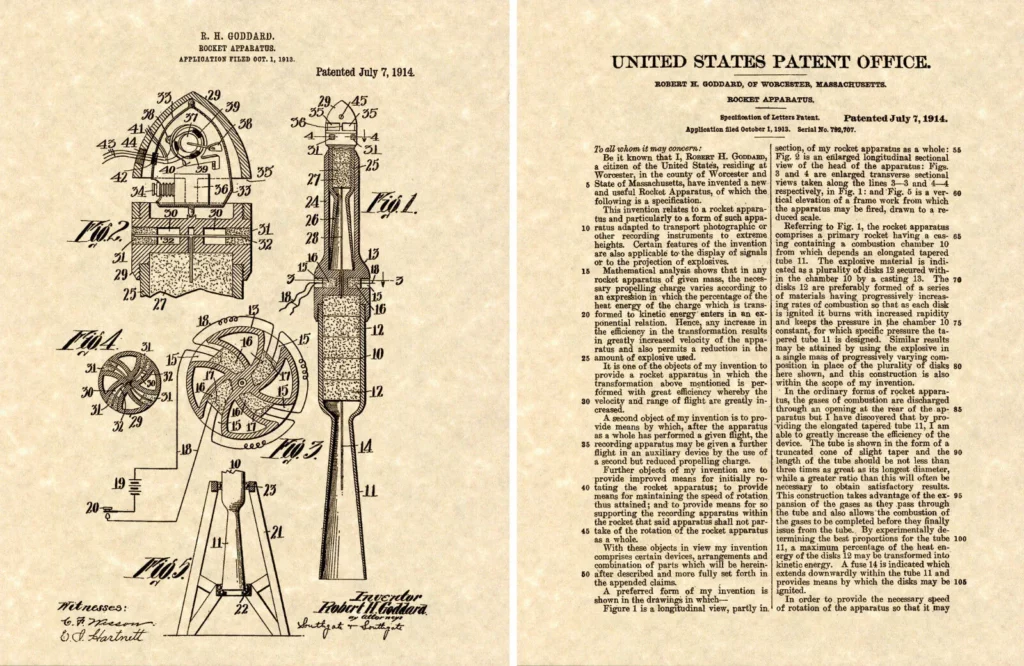

Goddard already had two rocket patents by 1914 – one using liquid fuel, and another for a two-or three-stage solid fuel variety. Despite this, the physicist’s ideas were ridiculed and met with skepticism by many in the scientific community who considered him to be a charlatan, causing the engineer and physicist to retreat from public life.

A New York Times editorial on January 13, 1920, dismissed Goddard’s ideas as “absurd”, claiming that, “it is obvious that a rocket could never be made to work in the thin air away from the Earth.” [3]

Six years later, on March 16, 1926, Robert Goddard launched the world’s very first liquid-fueled rocket which traveled 960m, reached an altitude of 12.5m, and attained an approximate speed of 95 km/hr.

The Lindbergh era

With little understanding of the significance of Goddard’s achievements, Lindbergh’s miraculous thirty-three-and-a-half-hour, 3620-mile, trans-Atlantic crossing of May 20-21, 1927, from New York to Paris led to the so-called Lindbergh Boom.

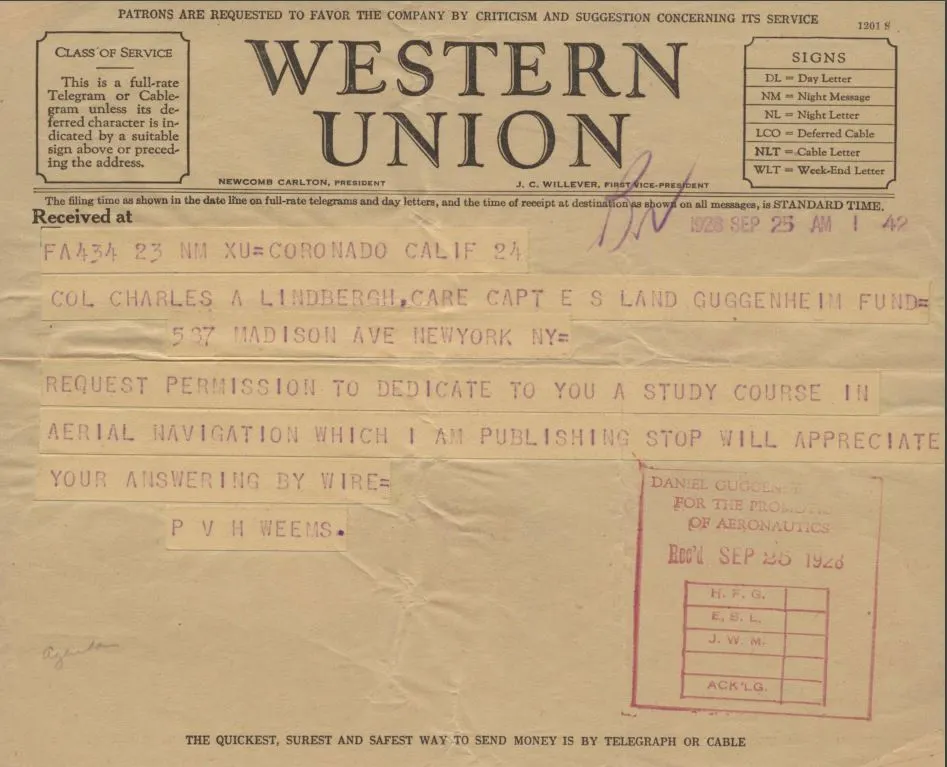

As the old saying goes, what a difference a day makes. So-called Lucky Lindy progressed from a relatively unknown airmail pilot to the most “celebrated living person ever to walk this earth” [4]. He was appointed as a technical advisor for Guggenheim’s Fellowship for the Promotion of Aeronautics in 1927, joining Orville Wright, another famous aviator, on the Guggenheim board.

Distinguished aviator, Elinor Smith Sullivan, later recalls this period: “People seemed to think we [aviators] were from outer space or something. But after Charles Lindbergh’s flight, we could do no wrong. It’s hard to describe the impact Lindbergh had on people. Even the first walk on the moon doesn’t come close. The twenties were such an innocent time, and people were still so religious—I think they felt like this man was sent by God to do this. And it changed aviation forever because all of a sudden, the Wall Streeters were banging on doors looking for airplanes to invest in. We’d been standing on our heads trying to get them to notice us but after Lindbergh, suddenly everyone wanted to fly, and there weren’t enough planes to carry them.” [5]

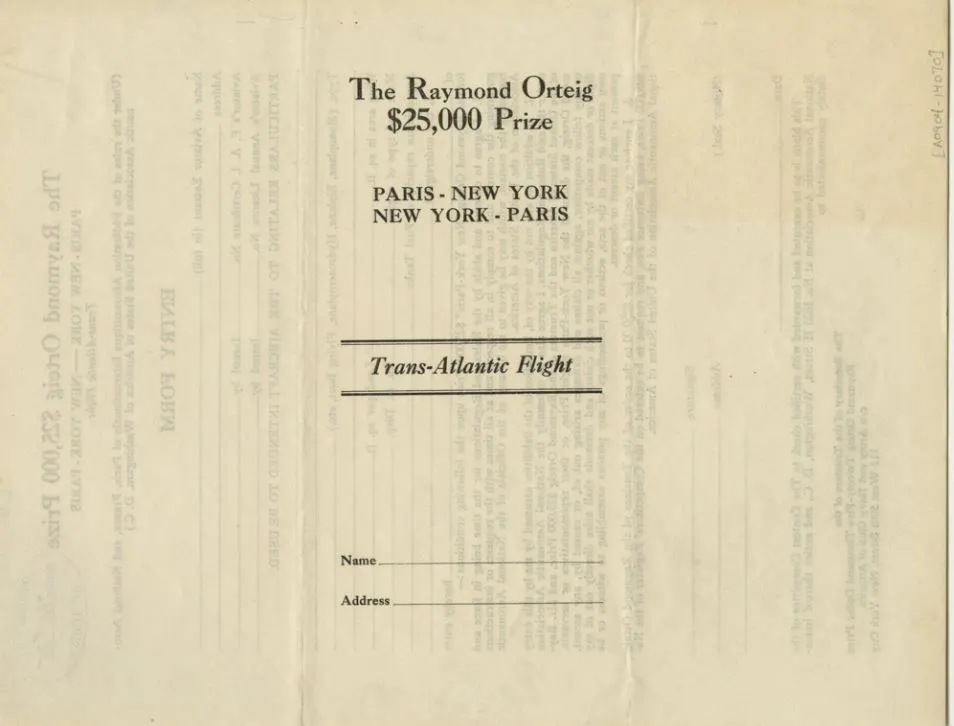

Lindbergh claimed The Orteig Prize, offered in 1919 by Raymond Orteig for the first non-stop flight crossing from New York to Paris or vice versa. This ushered in an era of change. “A landscape of daredevils and barnstormers was transformed into one of pilots and passengers. In 18 months, the number of paying U.S. passengers grew thirtyfold. . . . The number of pilots in the United States tripled. The number of airplanes quadrupled.” [6]

Lindbergh’s own words described that historic happening as follows, “I was astonished at the effect my successful landing in France had on the nations of the world. To me, it was like a match lighting a bonfire”. [7]

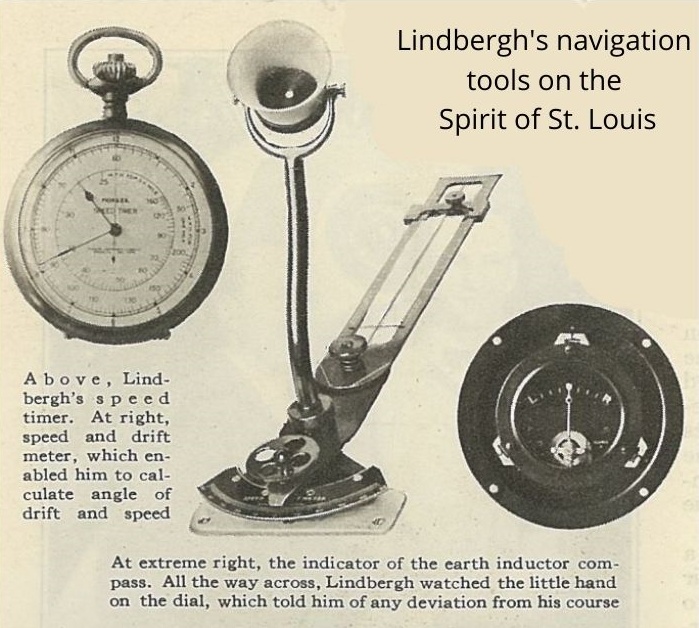

On a horological front, mystery always surrounded the timepieces that accompanied Lindbergh on that momentous record-breaking flight. Recent diary discoveries including a handwritten provisions list for the flight, indicate a watch & fob (ticked), and a stopwatch (unchecked).

Further, an instruments sheet checklist within his diary also notes a timer, likely a Pioneer-branded Speed Timer, and an aircraft clock, both unpriced. It is likely these horological ticking treasures accompanied Lindbergh on that momentous record-breaking flight, however, they would be upgraded in the period that followed.

Whilst aviation interest exploded, one of the most confounding challenges was the need to overcome the complexities of air navigation which had previously been achieved through the use of two techniques – dead reckoning and pilotage.

To this, radio and celestial would be added prior to the advent of radar technologies. This led to one of the most exciting periods of innovation in horological history, facilitating the development of complex purpose-built, unique timing instruments and navigational tool watches to aid in the determination of one’s position in the air.

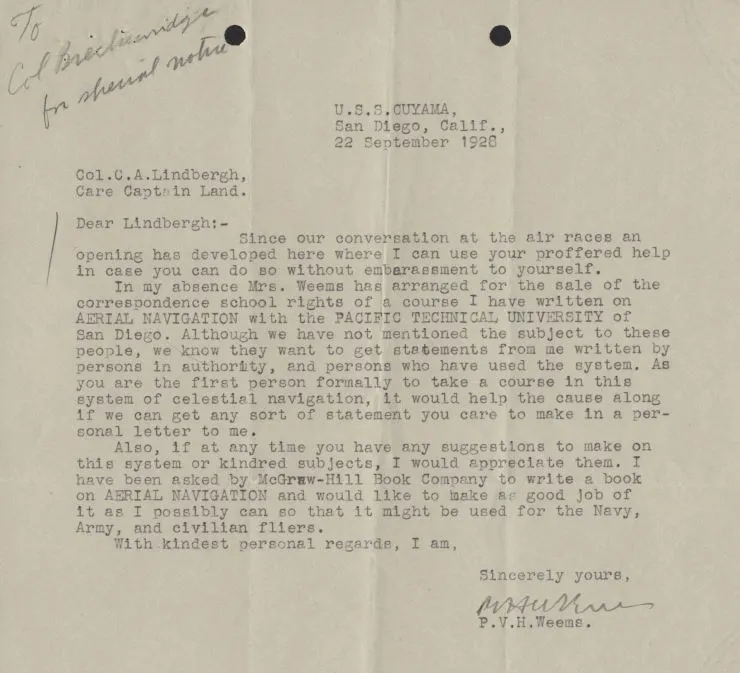

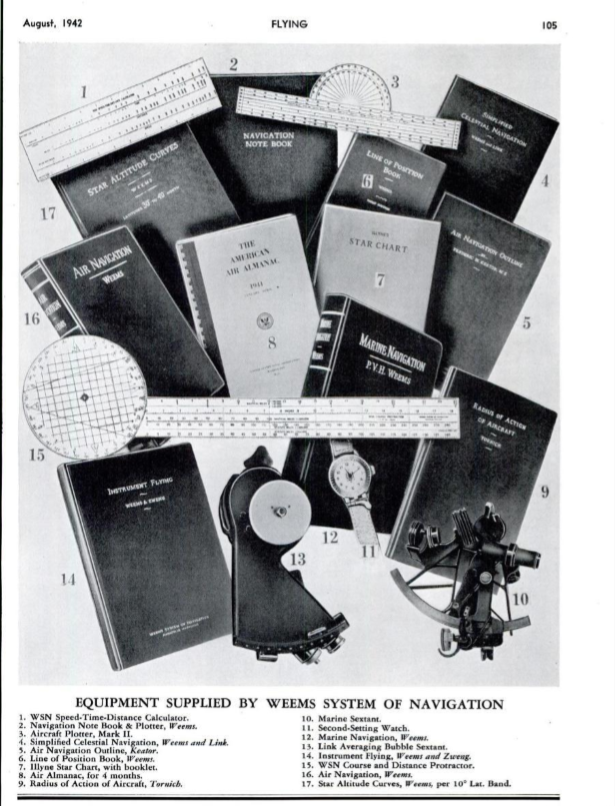

Credit lies with multiple parties. P.V.H. Weems, the man whose navigation system was central to aviation for three decades, modified a Waltham pocket watch making the world’s first second-setting watch.

This enabled adjustment of the second-hand against a known accurate source, or the so-called Greenwich Time Signal, which became known as the BBC pips.

Longines, at this time, were unparalleled in precision timekeeping and masters of innovation under their technical director, Alfred Pfister, who improved upon the hand-modified Waltham model, introducing an oversized wrist version, the Weems Second-setting watch.

Their American agent, Wittnauer, utilized the skills of John Heinmuller, a watchmaker and pilot license holder.

He was instrumental in timing and receiving recognition for all of history’s seminal flights and records. Heinmuller’s attachment, devotion, dedication, and relationships with the who’s who of the aviation space shaped a miraculous period of horological innovation and history.

The Longines Hour-angle watch

A friend, confidant, and in constant communication with Heinmuller, Lindbergh would design the most famous pilot watch in history, the Longines Hour-angle, which enabled a simplified and expedited calculation of longitude.

The very first prototypes arrived in January 1929 with the delivery of an aircraft calotte, and then ten months later, two prototype wristwatches.

One of these featured a calibrated turning bezel, the first wristwatch in history with a rotating bezel of this kind, and the other a dial with the unit of arc calibrations marked. Various modifications followed and a production version receiving patent approval from the International Office of the Industrial Property of Berne Switzerland was delivered to the market in October 1931.

The Hour-angle and Weems models ignited the development of specialist precision aviation timing instruments. They would be ordered by military departments and grace the hands of sky-bound aviators and aviatrix who pushed new frontiers and helped shaped the world we know today.

Dual 24hr and hour-angle calottes brought success to history-making flights from Paris to New York, all points in between, and enabled crossing the great oceans of the world.

Multi-scale, complex, and high-precision chronographs acquired two independent pushers and were made by Breitling, Heuer, Omega, Longines, Lemania, Rolex, Gallet, Minerva, Universal, Doxa, and a multitude of others.

The Moon Man

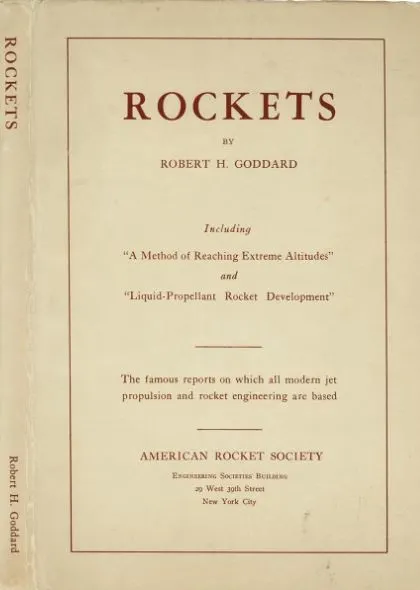

Lindbergh’s vision never stopped, and in 1929, he became aware of the pioneering rocket scientist and inventor Goddard. He was fascinated with his work, research, articles, and his published papers including – Liquid Propellant Rocket Development (1923) & Rocket Development (1926).

His participation with Guggenheim enabled him to apply his own expertise and experience to support aviation development, and advances in the space industry, and secure significant funding for ‘The Moon Man’, a belittling and mocking nickname Goddard acquired in the 1920’s.

Lindbergh’s involvement and appointment to senior government committees on aerospace development led to the creation of the successful ‘Lindbergh Line’. This expanded the successes of commercial aviation in the 20th century and was a series of air routes linking the United States with Central and South America.

It was launched by Juan Trippe, who owned Pan American Airways, in October of 1929. It marked a major milestone in the development of commercial aviation and established Pan American Airways as one of the leading airlines in the world.

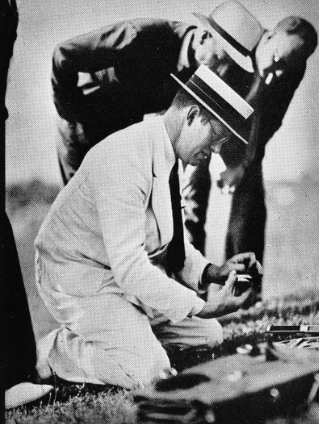

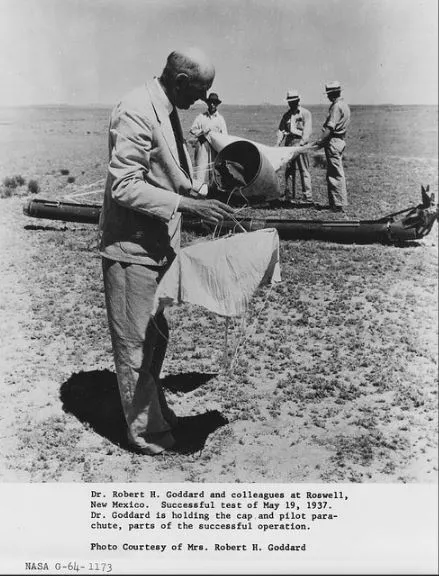

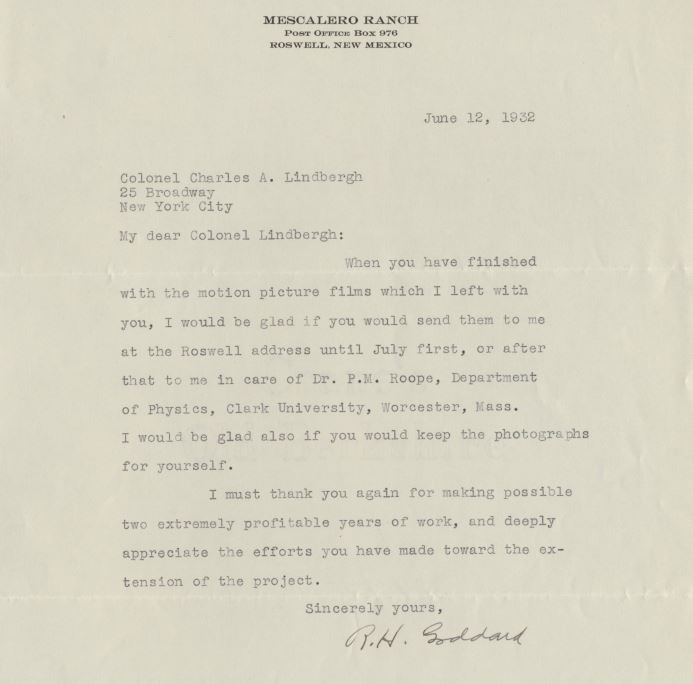

In 1930, Goddard took a two-year break from the physics department at Clark University, and with a small crew of workers moved to Mescalero Ranch in Roswell, New Mexico, to continue his research in seclusion. He was close friends with Lindbergh, thanking him by letter on June 12, 1932 [8], for securing (Guggenheim) funding for his projects.

Charles Lindbergh, an advocate for Goddard and his research, helped secure a grant from the Daniel and Florence Guggenheim Foundation in 1930. With that money, Goddard and his wife moved to Roswell, New Mexico, where he could conduct research and launch rockets while avoiding the scrutiny and criticism of his colleagues and the press.

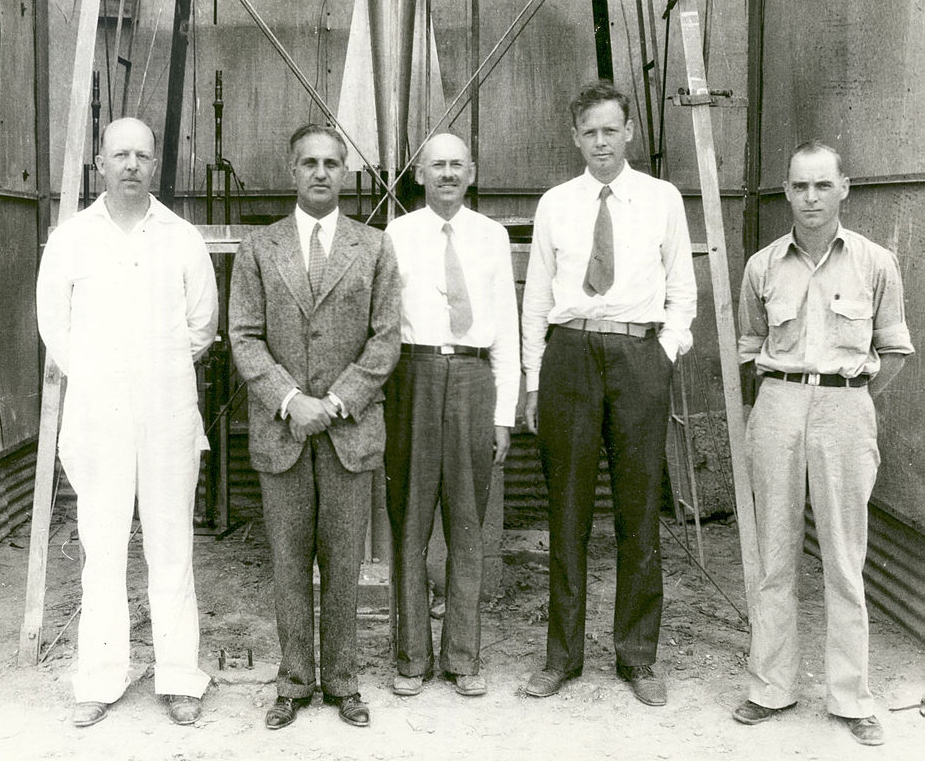

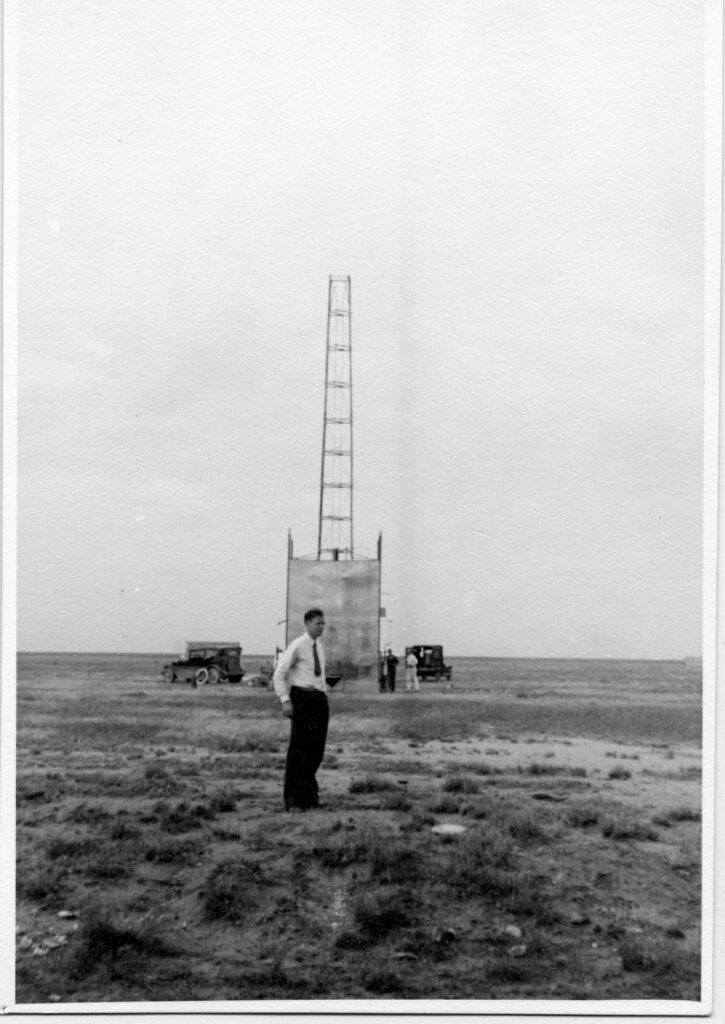

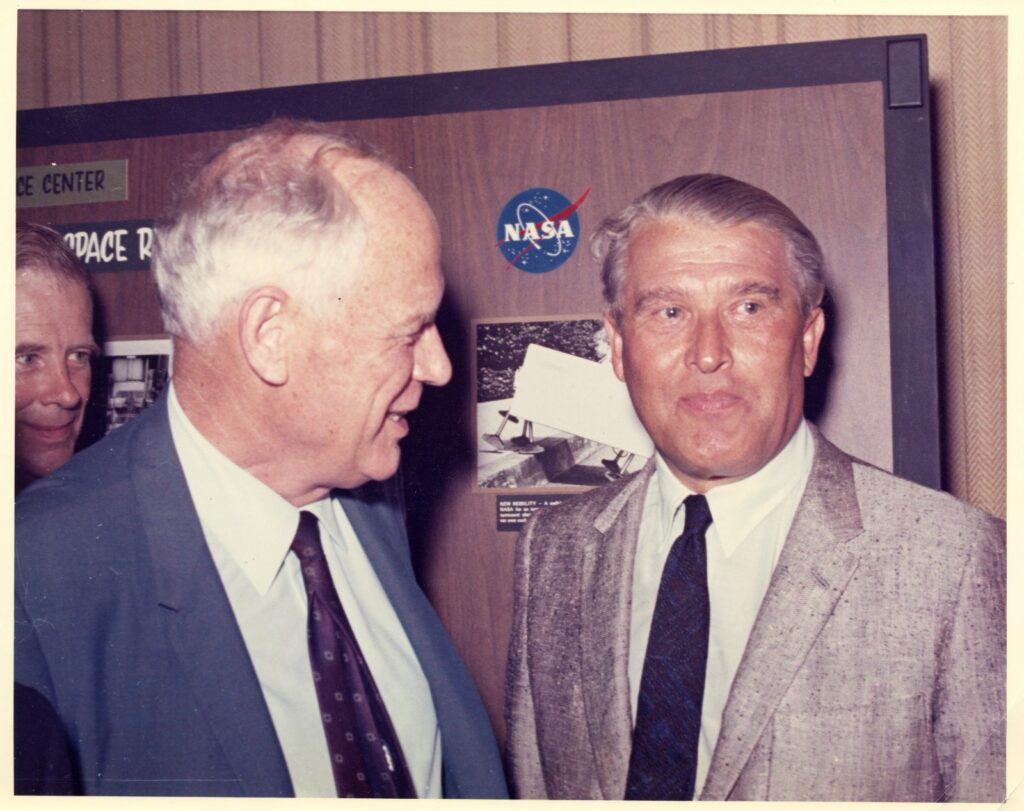

Standing in front of the rocket in the launch tower on September 23, 1935, are (left to right): Albert Kisk, Goddard’s brother-in-law and machinist; Harry F. Guggenheim; Dr. Robert H. Goddard; Col. Charles A. Lindbergh and N.T. Ljungquist, machinist.

Image courtesy of NASA, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The evidence for it being in the future was confirmed by Goddard’s real progress in the rocket stakes. On May 8, 1933, whilst in the midst of the great depression and funding pressures for science, Goddard wrote to Lindbergh “It appears that the rocket will have applications as an anti-aircraft weapon, owing to the high speed and controllability. You may remember that we have obtained speeds of over 500 miles an hour, with no attempt at lightness….” [9]

By the mid-1930s, Goddard’s rockets had broken the sound barrier at 741 mph and flown to heights of 1.7 miles.

Lindbergh proposed his own ideas for stratospheric flights, including the use of sealed and pressurized Stratosphere Tunnel, to test altitudes up to 50,000ft. The proposal lacked substance, and whilst he began advocating for rocket-powered aircraft and rockets, the technology was not advanced enough at the time and was considered impractical and more a vision of the future.

The Final Frontier

The need for something above and beyond the sky was noted by Goddard in one passage, “…as you have probably noticed, the public interest in the many scientific researches which ought to be carried out in the stratosphere…together with-altitude and high-speed flying appears to be increasing.” [10]

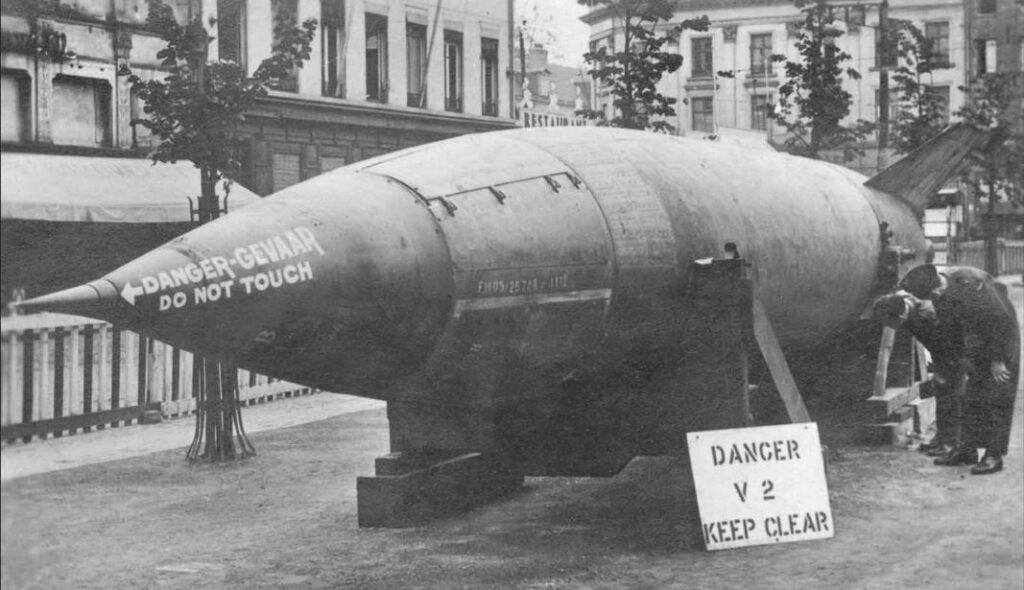

The space frontier arrived with Goddard’s early and experimental rocketry work and that of other scientists, engineers, and military figures attracting the attention and inspiring the German military and Wernher von Braun. Braun, a German engineer, and scientist was a key figure in the development of the V-2 rocket program that commenced in the early 1930s, with its first successful launch in October 1942. The V2 reached an altitude of around 95km, making it the first human-made object to reach space.

The catastrophic events of WWII, ushered in pilot watches made to military specifications. Robust, precise, at times oversized, featuring turning bezels and chapters, their requirements often included high visibility radium and other glowing dial materials to aid legibility and nighttime applications.

Horological creations from IWC, Lange, Stowa and Wempe – including the B-UHR, an oversized 55mm pilot’s watch – accompanied aviators in air raids.

Ministry of Defence (MOD), individual and commercial orders were placed pre, during and post war for watches meeting so called Mark IX, X, XI and Type XX specifications.

Depending on order requirements these were filled by IWC, Jaeger, Breguet, Breitling, Dodane et al. Weems second setting pieces were used by the English, Poles and Czechs in the Battle of Britain, by the US military and incredibly Imperial Japanese Navy pilots alongside the famed Seikosha in the skies over the Pacific.

Other three hand, Weems, split second, slide rule, hour angle, 24hour dial, sidereal time, and complicated pilot’s chronographs from a multitude of makers including Gallet, Lemania, Longines, Universal, Minerva, Nardin, Omega, Excelsior Park and Zenith became pilot’s chosen wrist companions. These aviator watches were used in a myriad of commercial, civilian and military applications.

The V2 program was of course a success for the German engineers involved and one of the most ambitious weapons development projects of the war. The advanced German technology and knowledge essentially caused the onset of the space race and would be used after the war by the United States, Russia et al.

Harry S. Truman approved Operation Paperclip, which saw Wernher von Braun and his team of German engineers and scientists brought to the United States to work on the Army’s rocket program at the Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, Alabama.

This paved the way for the American space program, and the formation of NASA on October 1st 1958. It was created under the National Aeronautics and Space Act which sought to coordinate and direct non-military space activity in the United States.

Taking its name from the gods, the Mercury Program, followed less than a week later on October 7th with intent to develop the technology, protocols and procedures necessary to launch man into space.

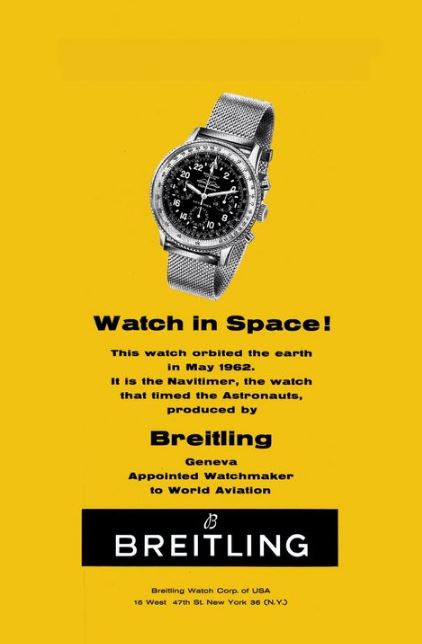

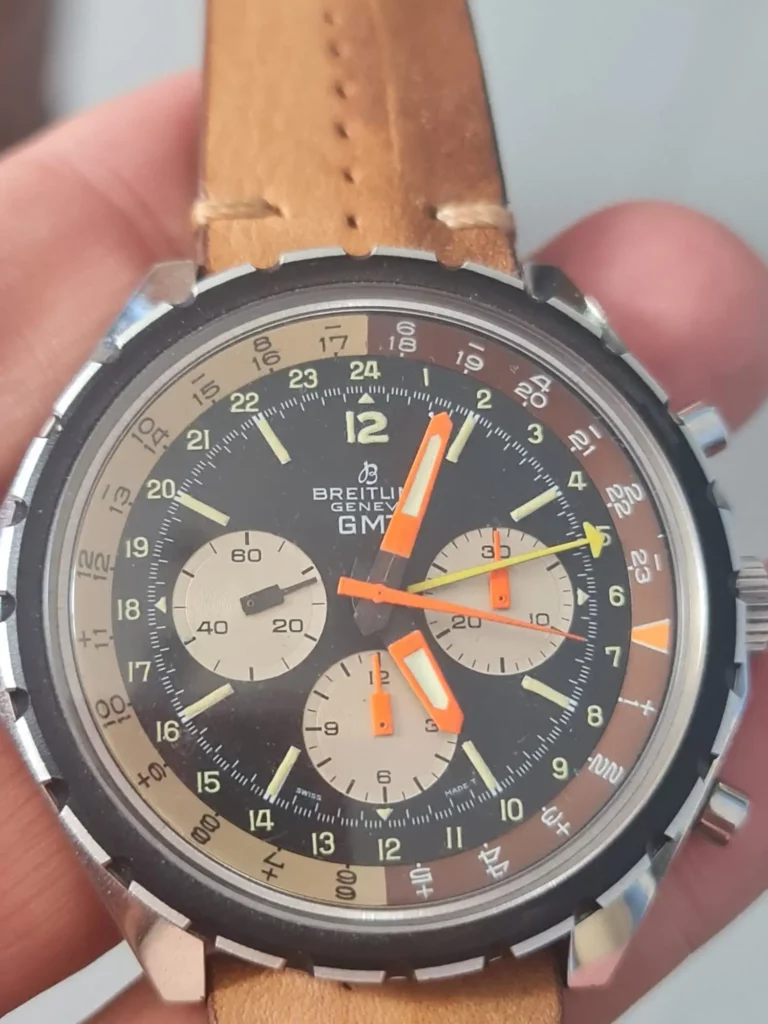

Success followed on February 20th, 1962 with John Glenn becoming the first American as part of the Mercury-Atlas 6 mission. This era necessitated specialist astronaut timing equipment and the birth of Breitling’s 24-hour Navitimer – the Cosmonaute.

The Astronaut name had already been reserved by Bulova and perhaps Yuri had a Swiss relative working in Breitling at the time.

Scott Carpenter’s design request and improvements to his R.A.A.F mate’s Navitimer had been taken on board by Breitling’s US subsidiary. The piece was delivered by Willy on May 20, 1962 – just four days prior to Carpenter’s Aurora 7 flight that orbited the earth three times over five flight hours.

The specialist Navitimer piece, would be renamed Cosmonaute and be the very first Swiss watch worn in space. It featured a wider bezel for use with gloves, a 24-hour dial and an extendable bracelet. In essence, it was the first watch designed and adapted for space use by an Astronaut and not NASA.

NASA

Von Braun served as the director of the Marshall Space Flight Centre, which developed the Saturn V rocket used to launch the Apollo missions to the moon. Von Braun’s team played a major role in the success of the Apollo program, and he retired from NASA in 1972, remaining a consultant until his death in 1977.

Robert Goddard, the father of modern rocketry passed away on Aug. 10, 1945, missing the age of space flight and receiving little attention for his 214 patents in propulsion research, guidance systems, and other technologies that contributed immensely to launch systems and the scientific exploration of space.

It was almost impossible to build a rocket or launch a satellite without acknowledging the work of Goddard and it wasn’t until the successful launch of the Soviet Union’s Sputnik satellite in 1957, and the launch of the first American satellite, Explorer 1, in 1958, that Goddard’s ideas began to gain widespread acceptance.

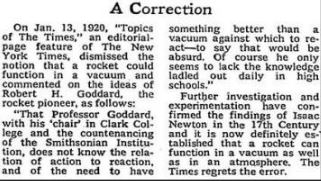

The New York Times admits its mistake

Vindication for ‘The Moon Man’ came a little too late, a day after Apollo XI set off for the Moon, in July of 1969, the New York Times printed a correction to its 1920 editorial section, stating that “it is now definitely established that a rocket can function in a vacuum as well as in an atmosphere. The Times regrets the error.”

Lindbergh’s dedication to aviation from the days of wooden planes to supersonic jets inspired countless people of all nations to pursue the skies and beyond. This love of flight endured well into the age of space exploration as he bore witness to the launch of Apollo XI.

Today, flight watches with 24-hour time, GMT hands, chronograph, and other complex functions now accompany those who fly the plane, many of those behind, and others on the ground in the jet set, fashion, transportation, military and commercial age. Many of these creations are looked at, admired, talked about, and collected, and hopefully one way or another their story finds its way to Flightbirds.

Lindbergh and Goddard’s far reaching legacies are still inspiring flight right into the 21st century. Whilst the former created history’s most famous pilot watch, the Longines hour-angle, to conquer the skies, Lindbergh played his small part in the need for, and in the formation of almost all pilot watches, including the Omega Speedmaster.

A watch that really is from the Sky to Space, and as their caseback states, ‘Flight qualified for all manned space missions’.

Both characters, alongside a passion for history, ticking treasures and their stories, all played a part inspiring Flight Birds: the hundred plus years of all pilot watches from Sky to Space.

Bibliography

Berg, A. Scott. Lindbergh, (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1998), as cited in Belfiore (2007)

Guthrie, Julian. ‘How Charles Lindbergh Inspired Private Spaceflight,’ Time, (AOL Time Warner: New York City, Sept. 20, 2016), http://time.com/4461689/how-to-make-a-spaceship/

Heinmuller John P.V. ‘IV Charles Augustus Lindbergh,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945).

A Method for Reaching Extreme Altitudes, Robert Goddard 1919(Smithsonian Collections).

NASA – Robert Goddard: A Man and His Rocket

Jennings, Peter. & Brewster, Todd. The Century, (New York: Doubleday, 1998).

Lindbergh, Charles. Charles Lindbergh An American Aviator (linbergh.com), http://www.charleslindbergh.com/history/index.asp

[1] NASA – Robert Goddard: A Man and His Rocket

[2] A Method for Reaching Extreme Altitudes, Robert Goddard, Smithsonian collection

[3] New York Times article January 13, 1920

[4] A. Scott Berg, Lindbergh, (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1998) p6

[5] Peter Jennings and Todd Brewster, The Century, (New York: Doubleday, 1998), pp. 420.

[6] The Raymond Orteig Prize (1919-1927): Challenge History (herox.com) Diamandis and Kotler

[7] A. Scott Berg, Lindbergh, (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1998) p135

[8] Letter to Charles Lindbergh from Robert Goddard June12, 1932 (Missouri Museum)

[9] Letter to Charles Lindbergh from Robert Goddard May 8, 1933 (Missouri Museum)

[10] Letter to Charles Lindbergh from Robert Goddard May 8, 1933