President Coolidge cabled Lindbergh noting, “The first flight of a lone aviator across the Atlantic crowns the record of American aviation…”. Whilst Lindbergh likely used a Waltham pocket watch and aviation clock for his record-breaking feat, the events of that day would soon lead to the creation of history’s most important pilot wristwatches – two prototype Longines Weems Second setting watches including the one of P.V.H Weems, a Weems transitional Hour-angle and a pair of improvised Hour angles which featured the world’s first rotating bezels. The three hour-angle pieces were all capable of making and expediting the calculation of longitude.

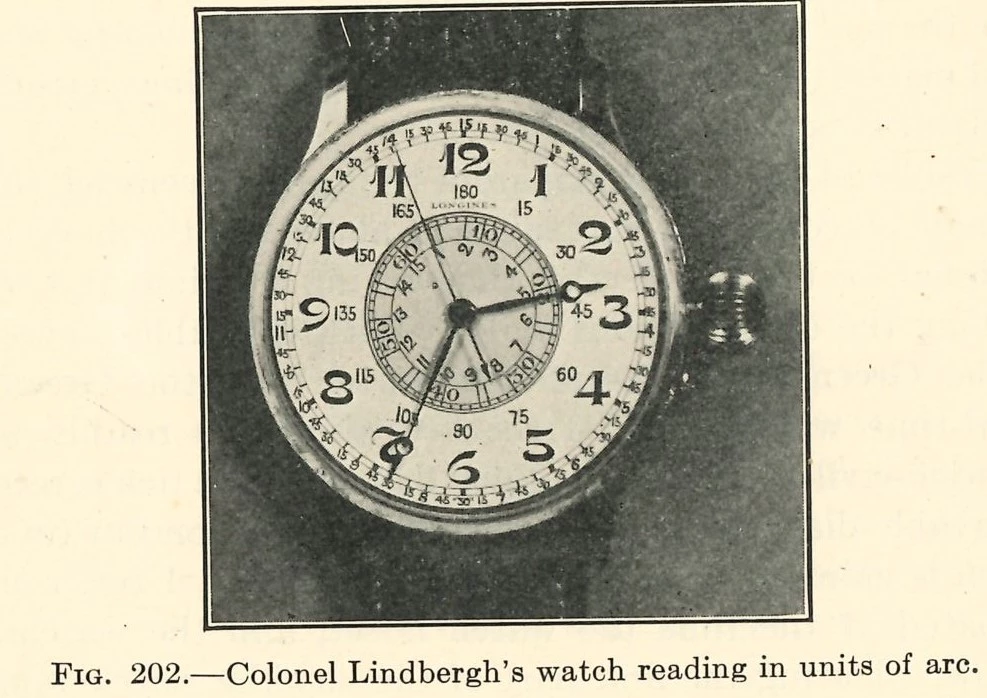

The recent discovery of Lindbergh’s modified Longines Weems prototype pictured in Weems first edition of his Air Navigation handbook casts clear evolutionary light on what is the world’s very first Hour-angle wristwatch.

The very first of these Hour angle prototype creations featured the unit of arc calibrations on a hand-edited Weems Second setting wristwatch enamel dial. Within months Longines and Wittnauer improved upon this with the creation of two calibrated turning bezel prototype wristwatches, making them the world’s very first calibrated rotating bezels of any manufacturer.

Longines enjoyed a multiple-decade zenith in the first half of the twentieth century and won more precision timing awards from the four great observatories of the world – London’s Kew-Teddington, the US Naval in Washington, and those in Neuchatel, and Geneva than any other maker.

During this time, Longines can lay claim to a multitude of horological firsts. A number of these are closely tied to the development of specialist, unique, precision, robust timing instruments for extreme conditions that sought to overcome the challenges of pre-radar air navigation.

Substantial credit lies with Longines technical team and its director, Alfred Pfister, who acquired the role in 1912. His success earned him a dual role that later included the managing director title of Longines in 1927. Both roles continued till his passing in 1949.

Another key architect was John Heinmuller who left the St Imier manufacturer as a 22-year-old skilled watchmaker in 1912 to join Wittnauer, the American agent for Longines. His actions and business acumen joined Longines at the hip to aviation timing and ensured they were the pen-ultimate supplier of innovative, robust, and precise aviation timepieces to flight pioneers, expeditions, commercial airlines, and the military. By 1919, Longines was the official supplier and sponsor of the Federation Aeronautique Internationale (FAI) and worn by aviation’s who’s who.

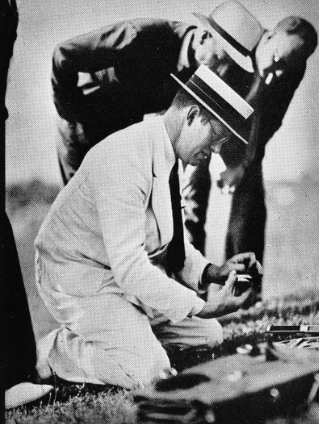

Image – Heinmuller – Man’s Fight to Fly.

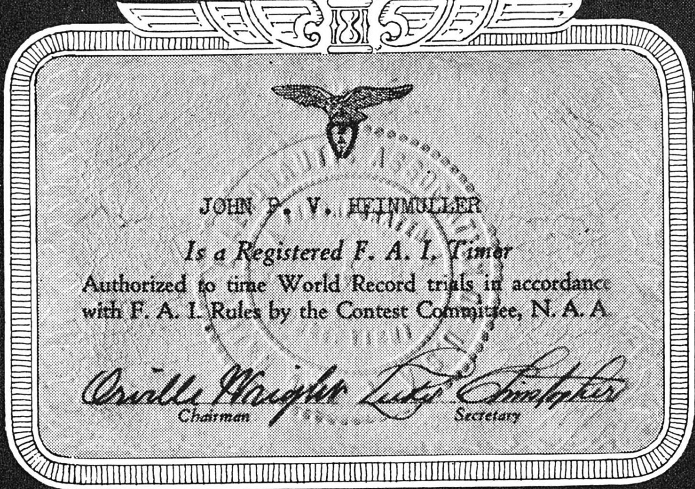

Heinmuller held a pilot’s license, demonstrated a flair for precision, organization and officially timed most of these seminal flights whilst serving as the official timer of the National Aeronautic Association(NAA), and the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI). He occupied this role for thirty years and was responsible for timing no fewer than 34 record-breaking flights prior to the outbreak of World War II.

John Heinmuller was the official timer for the Federation Aeronautique Internationale. He recorded and brought recognition to history’s seminal flights and attached Longines at the hip to supply new, experimental, and essential timepieces to aviation’s who’s who.

He also organized ‘the Timing Contest Board of the National Aeronautic Association in accordance with the chronometric specifications of the Federation Aeronautique Internationale.’[1]

The dangers of early aviation cannot be overstated, out of seventy-eight attempted transatlantic flights up until 1944, just eleven were successful, with thirty-nine ending in complete catastrophe and the other flights considered failures without the loss of lives. Heinmuller’s unrivaled commitment to aviation and horology earned him the nickname Aero One.

He was involved in planning, development of specialist instruments, detailed record keeping and gained recognition for the majority of history’s greatest aviation achievements – enshrining them into the record books forever. He went on to become vice (1921), and later president of the new Longines-Wittnauer Co entity in 1936.

Already familiar with the intricacies of watch construction, Heinmuller ‘developed a complete line of navigation timing equipment, including aviation dash-board clocks, turn and bank indicators, altimeters, speed indicators, and compasses in cooperation with outstanding scientists of the day.’[2] He participated in innumerable test flights where these specialist timing pieces and instruments were put through their paces benefitting air navigation and helping to shape its future.

Pilot’s lives depended on the reliability and accuracy of aviation timepieces and technical instruments as well as their ability to use them. The 1920s saw speed, altitude, distance, and duration record-making attempts being made on an almost daily basis. Aluminium and dramatic improvements in engine performance, size, and reliability aided and enabled this golden age of aviation. However, just like Harrison’s conquest of calculating longitude on the sea 200 years earlier, air navigation over unchartered lands and water, at night, accounting for wind drift, and in poor weather, presented a complex set of new challenges.

The grandmaster of air navigation and the father of the modern-day G.P.S system, P.V.H Weems whose air navigation techniques were used for three decades stated, “It is perhaps fortunate that timepieces were developed before radio, or else extremely accurate timepieces would probably never have been made”.[3]

Weems famous second-setting wristwatch was born with the help of the Longines technical team and its predecessor the Touran dual-time pocket watch that was originally made for the Turkish market.

The recent discovery of Lindbergh’s aircraft calotte that was edited for the unit of arc calibrations and the very first Longines hybrid hour-angle wristwatch (montre angle-horaire) cast clear evolutionary light on what is one of history’s most important aviation instruments and pilot wristwatches ever made.

The hand-edited Weems hybrid creation, sported calibrations for the unit of arc on the dial and was pictured in the first edition of Weems Air Navigation book published in September 1931. It was made by hand editing the Z.J.Fluckiger enamel dial of one of the very earliest Weems wrist Aerochronometers that was part of the first production order #1395 made by Wittnauer in 1929.

All pieces of this order were second-setting production wristwatches, using the famous Longines 18.69N pocket watch caliber. They were delivered on April 4th and May 2nd, 1930, and the unit of arc dial modifications were most likely made to the dial by P.V.H Weems for Lindbergh.

Heinmuller met Lindbergh shortly after he broke the US transcontinental speed record from Los Angeles to New York on April 20, 1930. In a letter to his wife, he wrote “…I was privileged to work out details of his latest instruments with him as the enclosed design from him will show. Keep it for our records. His latest ideas incorporate a second setting device for Greenwich Time, taken from the radio. The device… permits laying down of a position in less than three minutes. Navy experts at Annapolis say it is the most outstanding aviation improvement in many years”.[4]

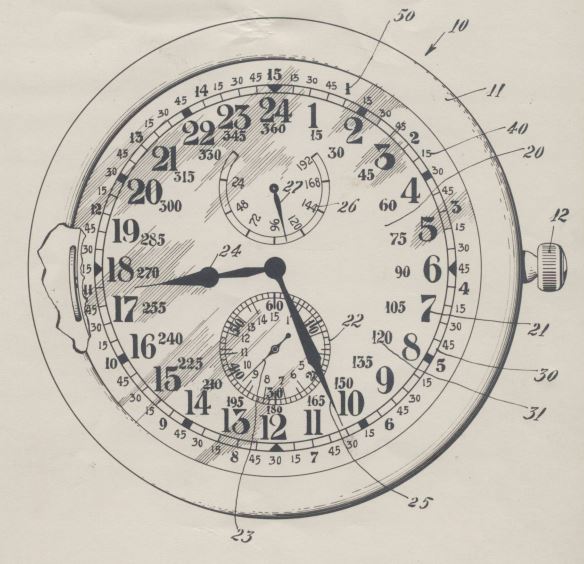

The new wristwatch with serial number 49315xx, had a dial that mirrored the layout on the aircraft calotte of Lindbergh’s that was delivered a year prior but modified with unit of arc calibrations a few months earlier.

The dial and inner chapter of the very first hybrid wristwatch allowed a pilot to establish their position in degrees, and units of the arc based on the calibrations on the dial and inner chapter.

This experimental tool watch used green, red, blue, and black for dial scales and calibrations too as they experimented with legibility. Longines and Wittnauer improved upon it within months with the delivery of the world’s first calibrated turning bezel prototype hour-angle wristwatches.

To date, just two prototypes with rotating bezels have surfaced, and it was described in the New York Sun in 1931 as an Air Device developed by Lindbergh and used by Anne and Charles on their trip to the Orient in 1931. The prototypes with edits would later morph into the first version of the Longines hour angle production models sold in December 1931.

Wittnauer took delivery of an eight-day aircraft calotte with calibre 24.41 serial 4307253 on the 25th of January 1929. The ultimate recipient was Lindbergh, and correspondence between Heinmuller and

Lindbergh likely points to this exact clock having the units of arc scales added to the dial by Weems himself. Essentially making it the world’s first production hour angle timepiece.

It was initially delivered just two months after the delivery of the first-second setting prototype of Weems himself in November 1928. However, like the early prototype Weems hour angle watches, hand editing was done post-delivery.

A letter from the 14th of July 1930 between the two parties noted, “The minute arc has been prepared by Lt.Comm. Weems who worked several hours on the division of the dial in this office…”.[5]

Further, correspondence from the 30th of September from Heinmuller when discussing the development of a wristwatch notes that “we will make a moveable bezel on the new timepiece” [6].

However, this process was still a work in progress, and a letter on October 17th from the US agent’s representative notes, “that the new Weems navigation watch is just finished with degree reading according to your specification. We have not made the bezel moveable. In as much as the equation of time is continually changing, and from what we have heard from different navigators, the bezel idea would not work out satisfactorily… make some try-outs with this timepiece and advise us of any other changes or ideas you would like incorporated in this Weems navigation watch”[7].

The bezel issue is also addressed in Weems Air Navigation book first published in September 1931. The book states, “in order to set the proper equation of time on the watch without moving the hour and minute hands, a moveable bezel working on the same principle as the second-setting feature of the aero chronometer is fitted to the watch. The markings on the bezel are in degrees and minutes of arc only…”.[8]

The recent discovery of early 1930s correspondence between aviation’s playmakers Heinmuller, Lindbergh, and Weems, and the discovery of these early prototype watches now colour these remarkable flight birds and reveal a bit more of its incredible development history. The watch enabled a simplified calculation of longitude by using the hands of the watch to give you time in hours, minutes, and seconds.

A patent request was filed for the “Montre angle-horaire”, with the International Office of the Industrial Property of Berne, Switzerland, on the 29th of September 1931, and it was approved just two days later. Longines archives indicate that the very first Hour-angle production watches were delivered in December 1931.

The Longines Weems second Setting wristwatch and the improved Hour-angle are without exception the two most important pilot watch models in history. Their ninety-plus year evolution and development placed them at the forefront of instruments needed and relied upon by the who’s who of aviation’s golden era.

The recent discovery of the incredible original prototype timepieces and early correspondence by the key playmakers in their development helps colour and write a new chapter in Longines and pilot watch history. Their very evolution led to the creation of the world’s very first calibrated turning bezel wristwatches of any maker.

[1]Anonymous, ‘Collectors: John P.V. Heinmuller,’ Arago: People, Postage and the Post,’ (Smithsonian National Postal Museum), http://arago.si.edu/category_2040919.html (date accessed: 02/09/16).

[2] Anonymous, John P.V. Heinmuller, (Little Buttes Publishing Co.), http://littlebuttesbooks.com/blog/john-p-v-heinmuller (date accessed: 02/09/16).

[3] Air Navigation Weems 1931 first edition p399

[4] Man’s Fight to Fly John Heinmuller, Funk & Wagnalls Company p75

[5] Letter between John Heinmuller and Lindbergh July 14, 1930. Missouri Museum box 42 folder 16

[6] Letter between John Heinmuller and Lindbergh September 1930. Missouri Museum box 42 folder 16

[7] Letter between John Heinmuller and Lindbergh Oct 17, 1930. Missouri Museum box 42 folder 16

[8] Weems Air Navigation first edition McGraw-Hill Book Company p411

Wonderful research thank you for sharing the details. The wonderful pictures really help to show the evolution of these important timepieces⏱️

Greetings Ricky… many thanks for the feedback and comments it makes it all worthwhile. I have recently bought the prototype Hour-angle wristwatch and the world’s first wristwatch with a turning bezel and a story on that front will be published shortly. Thanks Andy 😉

That’s Amazing Andy!

Greetings Seiji… an incredible piece of aviation and horological history being pieced together like a 10,000 piece jigsaw puzzle. I always appreciate and love the feedback. It makes it all worthwhile writing if someone reading. Andy