The speed of the plane brought complex new navigational challenges. When traveling at 200 miles an hour, a kilometer is covered in just eleven seconds. Countries (including island fuel stops) quickly disappeared – bringing oceans, uncharted territory, and a risk to life if navigational calculations were wrong. The Hour-angle watch – a “Lindbergh” brought a degree of certainty on that front.

Longitude on the Fly

Just as Harrison’s quest for the mastery of longitude, sea navigation and his development of marine chronometers almost 200 years earlier, air navigation came to the fore. Pilot’s lives depended on the reliability and accuracy of aviation timepieces and technical instruments as well as their ability to use them. Radio signal accuracy allowed perfect and easier time synchronization worldwide.

This expanded significantly in February 1924, when the British Astronomer Sir Frank Dyson developed the famous BBC “pips” using two mechanical Royal Observatory clocks which became known as the Greenwich time signal.

Philip Van Horn Weems

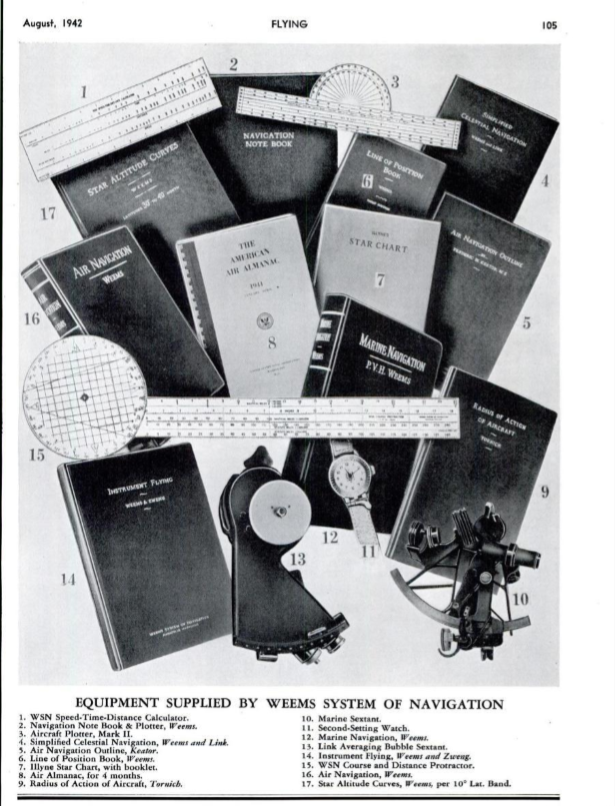

The grandfather of today’s GPS system and the backbone of this air navigation age was Lieutenant Commander Philip Van Horn Weems (1889-1979). He was a pilot and master navigator who published a number of papers and books. His Weems System of Navigation training courses, first operated by the master navigator, Harold Gatty, were soon adopted by the US Navy, commercial airlines and aviation greats including Byrd, Amy Johnson and Lindbergh.

Post his Atlantic success, Lindbergh nearly suffered a tragic outcome after getting lost in ‘The Spirit of St Louis’, on a flight from Cuba to Florida… a haywire compass, stars shrouded in haze, and nothing recognizable from pilotage on the Florida map. Lindbergh’s inexperience and the challenges of air navigation (avigation) led to his 1928 meeting with P.V.H Weems, a young naval officer who was an instructor at the Naval academy in Annapolis.

The outcome likely changed avigation forever. Lindbergh’s notoriety and air navigation inexperience was promoted by Weems and he was soon being actively trained by P.V.H Weems using his System of (Air) Navigation. Lindbergh took up studies in celestial navigation, Line of position and star altitude curves which greatly sped up and improved the determination of one’s position.

With the help of star charts and Polaris (the northern star) the navigator was able to help find his clarify his possible position using two stars in a little over 30 seconds.

Before 1928, watches were used with sextants for celestial calculations and accurate only to one minute. The development of Weems second setting watch allowed for +/- 30 second adjustment, this dramatically improved time synchronization with a radio signal and avigation itself. A watch error of thirty seconds could have catastrophic consequences and could account for up to seven miles difference in one’s position.

Pilot’s lives depended on the reliability and accuracy of aviation timepieces and technical instruments as well as their ability to use them. At first, his second setting ideas were brought to life using modified Waltham Vanguard pocket watches.

The Two Most Important Aviator Timepieces

This remarkable time would soon serve as the backdrop for the creation of the two most important aviator’s timepieces ever made: the Longines Weems ‘Second-setting’ watch which allowed for improved time synchronization, and Lindbergh’s modified Weems ‘Hour-angle’ model which simplified longitudinal and other navigational calculations.

With just a pair of hands and a dial, a watch could be used to calculate gasoline consumption, ground speed, load-lifting capacity, tell time and navigate using celestial observations. Weems devoted his lifetime toward improving instrumentation and navigation techniques for long distance flying.

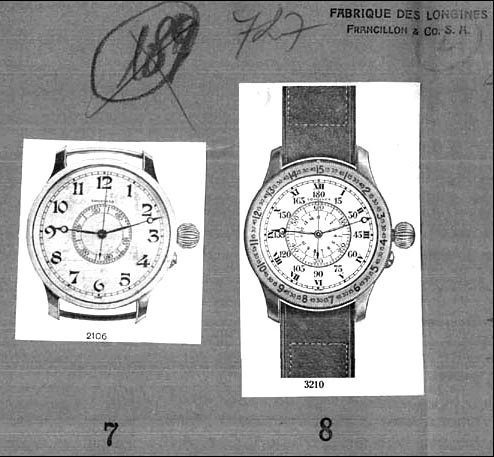

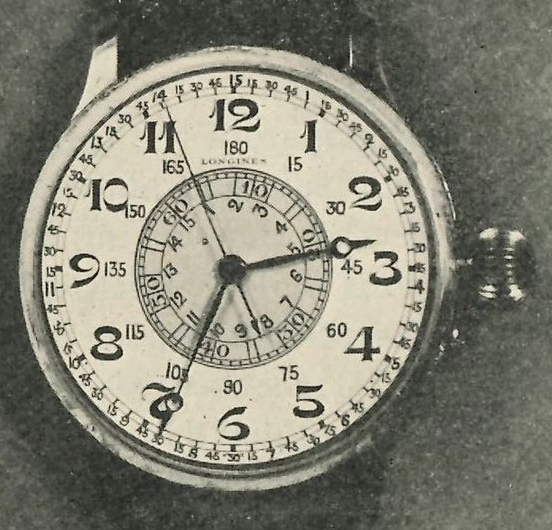

The first Longines Weems made in an all silver case was delivered on the 30th of November 1928 to Longines-Wittnauer bearing serial number 3585867; the ultimate owner being none other than its original designer and architect, Philip Van Horn Weems who had developed the watch requirements with the Aircraft squadron’s battle fleet. The central chapter on this new Longines Weems model allowed for the exact second to be set, relative to the hour and minute hands. The inner chapter ring disc could be rotated in either direction to gain an additional accuracy of +/- 30 seconds by using a radio signal or other known exact timepiece.

Rear Admiral Moffett, who was the chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics for the US Navy Department stated “The suggestion… as to a moveable second- hand dial is considered to be a very valuable one, greatly facilitating the process of keeping a clock set to the exact time.” [1] Developed specifically for aviators with the Aircraft squadron’s battle fleet, it was officially designated as a “second setting navigation watch” [2] by the U.S Naval Observatory.

It was later distributed by them to the US Naval air stations and fleet along with filling private and government orders for the next fifteen odd years.

The History of the Avigation Watch

Today Weems’s actual Longines ‘Aerochronometer’ watch as described in his 1931 Air Navigation book rests in the Smithsonian, absent its crown and is one of history’s most important pilot watches. Adopted by Weems, the name and part of its function lies with the man Lindbergh described as the “Prince of Navigators,” Harold Gatty. He originally used the term to describe a timing device which offset aircraft speed inaccuracies when making navigational observations.

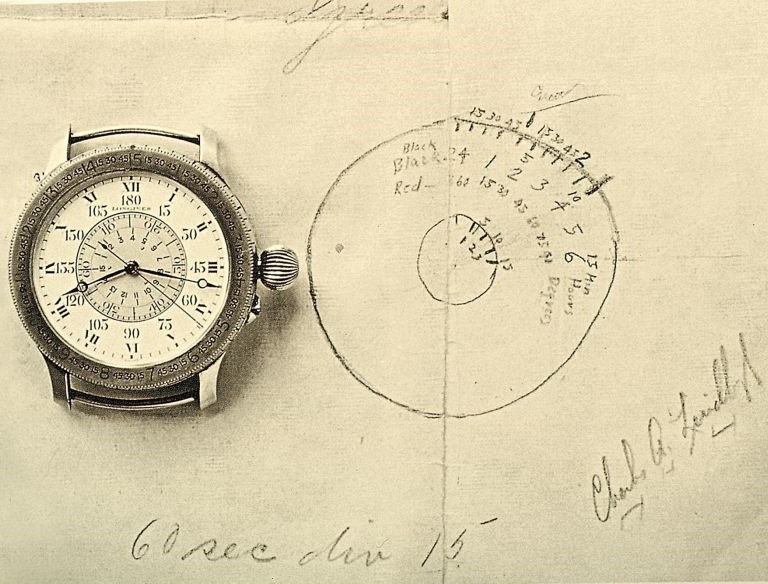

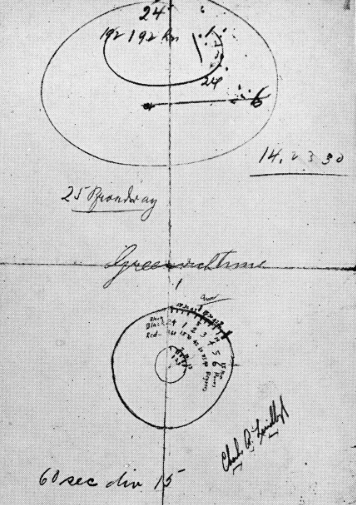

Whilst little is known of the watch worn on Lindbergh’s successful Atlantic crossing in May 1927, we do know that Lindbergh owned a special aircraft calotte with serial number 4307253. The calotte’s dial was also marked up units of arc exactly like the ‘Lucy’ Weems, pictured in the Air Navigation book of 1931. The watch was a hand edited hybrid Weems hour angle watch of sorts, with a dial featuring notations for units of the arc and this was the precursor to the most famous drawing and watch in Longines history.

Weems wrote comments in the first publication of Weems Air Navigation book noting that Longines were working on a graduated dial in arc, not time, along with “… a moveable bezel working on the same principle as the second-setting feature of the Aero Chronometer is fitted to the watch. The markings on the bezel are in degrees and minutes of arc only.” [3]

Essentially, Lindbergh’s Weems watch was most likely part of the very first commercial delivery to Wittnauer in May 1930. The unit of arc improvements allowing for calculation of longitude would soon be added to his Weems watch, (likely with the help of the watches creator), whilst he waited for the delivery of his new dedicated Longines Hour-angle watch.

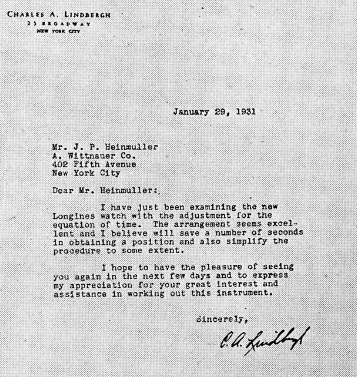

It is known that Heinmuller met Lindbergh shortly after he broke the US transcontinental speed record from Los Angeles to New York on April 20, 1930. In a letter to his wife, he wrote “…I was privileged to work out details of his latest instruments with him as the enclosed design from him will show. Keep it for our records. His latest ideas incorporate a second setting device for Greenwich Time, taken from the radio. The device… permits laying down of a position in less than three minutes. Navy experts at Annapolis say it is the most outstanding aviation improvement in many years”. [4]

Lindbergh, his hybrid “Lucy” watch, Weems, Heinmuller and the Longines technical team in St Imier were the formative pieces bringing life to Lindbergh’s famous 1930 drawings and delivery of Hour-angle production prototypes in December 1930.

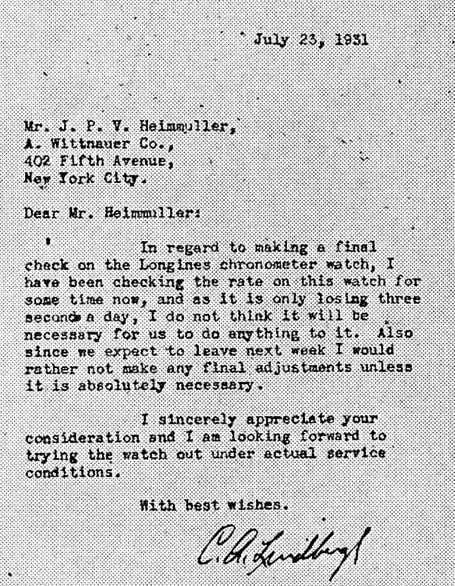

Lindbergh had been delivered an Hour angle prototype watch by John Heinmmuller, who on June 5, wrote to Lindbergh commenting, “The special watch you designed is now ready. Lt Weems impressed with the new design. Make appointment to see sample”. [5]

We can surmise that the letter was in relation to the hour-angle prototype serial 4931576 that featured the world’s first calibrated turning bezel. This was discussed but not featured in Weems book, leaving open the possibility that the prototype hour-angle in Weems book somehow made its way to Weems or Lindbergh earlier?

Edits must have been noted to this piece by Lindbergh as Heinmuller noted, “on 20 December 1930, the prototypes are now ready”.[6]

Lindbergh noted he was examining the watch in a letter to Heinmuller in January 1931 and commented on its perfect timing in July.

A patent request was filed for the “Montre angle-horaire” with the International Office of the Industrial property of Berne Switzerland on the 29th September 1931 and approved two days later for history’s most famous pilot watch.

It could calculate longitude, the hands giving you time in hours, minutes, and seconds, whilst the bezel and the inner chapter allowed you to establish your position in degrees, and units of the arc based on the bezel graduations and inner chapter markings.

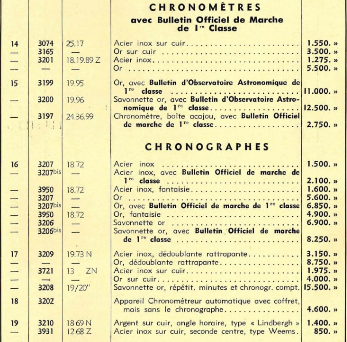

Two basic reference numbers, 3210 and 4365 existed for the approximate 15-year life of the large 46mm hour angle or so called “Lindbergh” model and the watch was made in silver, steel, a handful in chrome and six pieces in 18k gold. The Lindbergh arrived during an unusual juncture in history. The great depression of October 1929, led to a wholesale collapse in Longines sales in America and with it the fortunes of the Wittnauer family ownership.

By 1931, sales had dwindled to the lowest point since A.Wittnauer Company was formed and Longines were only delivering pieces to Wittnauer on a stop gap basis. By 1935, Martha Wittnauer was on the verge of bankruptcy. It truly was the end of an era, and Martha Wittnauer sold the company to the Deltah Company in 1936.

Its fortunes were significantly reversed, and a few short years later, it accounted for almost 80% of Longines global sales as the great war beckoned.

It is hard to get an exact handle on how many hour angle watches were sold. Early Longines archives indicate that there were four years between manufacture and sales date for a number of Hour-angle pieces between 1931 and 1937. A few reasons can possibly explain the small number of sales of the Hour-angle watch in the American market. The Great Depression already noted led to a complete sales collapse in Longines watches and it almost ran parallel with the introduction of the Hour-angle watch. The Lindbergh child kidnapping of 1932 and the subsequent Hauptman trial of 1935, saw the Lindbergh family move overseas.

Further, Lindbergh was engaged by both the Americans and the British for two years from 1936 inspecting German airforce capabilities. Lindbergh was soon controversially cast by Roosevelt politically in a smear campaign as a German sympathizer, anti-war activist and anti-Semite. The two men clashed on ideas, opinions, and the actions of the day essentially divided the American nation and Lindbergh’s reputation would essentially be smeared forever.

Lindbergh’s voice against American involvement in the war and his political aspirations significantly cut short sales and promotion of any large Hour-angle model sales in the American market. Seemingly, the vast majority of Hour-angle pieces were delivered internationally, whereas the large Weems model were almost all exclusively delivered to the US market.

Pilot Input and The Development of the Hour Angle

Pilot input would shape aesthetic and technical changes to the Hour-angle model to improve legibility and function. Essentially, there are four different versions of the watch, changes were made to the case profile and material, the bezel, dial, and movement over its life. The earliest examples used all silver cases with three different profiles: the first, a very thin flat case with minimal downward extension of the lug.

Two more case profiles followed using thicker cases with progressively more curvature of the lugs. Steel would almost exclusively replace the silver case for the last two versions of the watch. The exception seemingly involved a single delivery of a rare handful of all silver fourth generation pieces received by the Italian agent Ostersetzer, in September 1942.

The bezels on all Hour-angle pieces were handmade in silver with subtle variations. The first two featured green and black enamel numbering, whilst blue was used on the last two iterations.

Font size increased dramatically, approximately 30-50% on the second and third bezel versions increasing the functionality of the unit of arc markings.

The bezel knurling also differed between the different generations. Similarly, in 1938, blue was added to the all-black enamel dial to increase legibility. In October 1940, the pin set 18.69N caliber changed to the 37.9 (this appeared in 1938 for the Weems model) and then to the 37.9N which was introduced to the market in 1940, seemingly appeared in Lindbergh models in or about 1941/2.

Nothing can overstate the significance and the role these two Longines watch models in large execution played in air navigation, establishing one’s position in the air, and the pen-ultimate success of aviation as a whole.

Out of seventy-eight attempted transatlantic flights up until 1944, just eleven were successful, with thirty-nine ending in complete catastrophe and twenty failures without loss of lives. Today, monuments recognizing aviation’s pioneers grace airports, history books, museums hold their stories and as a consequence, we enjoy flight of a truly different kind today.

A Longines-Wittnauer shop display from the late 1930’s including watches from this remarkable time states, ‘The Heroes of Aviation and Exploration use Longines-Wittnauer watches for navigating and timing world records’. An incredible list of aviators and aviatrix depended on the Longines Weems, and Lindbergh pieces as accurate and essential instruments with their lives. Lindbergh noted, “Accuracy means something to me. It’s vital to my sense of values. I’ve learned not to trust people who are inaccurate. Every aviator knows that if mechanics are inaccurate, aircraft crash. If pilots are inaccurate, they get lost-sometimes killed. In my profession life itself depends on accuracy”.[7]

The Lindbergh and Weems were special technical tool watches and flying instruments, used by many known aviators and aviatrix, the so called who’s who, with many remaining household names to this day for those with a knowledge of history. Rapid advancements and changes to radar and radio communication greatly changed the navigational needs of pilots and tool watches of this kind, limiting their window for use.

In reality, a range of factors limited production of these aviator tool watches – the Great Depression, rapid technological changes in communication and radar and the inherent dangerous nature of commercial and military aviation pursuits in the thirties and forties. Today, a small sprinkling of the pen-ultimate pilot’s precision tool watch remain. They heralded from an incredible chapter and time, the golden age of exploration, aviation and adventure, when real aviation heroes and heroines helped shape, change, and color the world we know today.

__________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Air Navigation Weems 1931 first edition p400

[2] Air Navigation Weems 1931 first edition p400

[3] Air Navigation Weems 1931 first edition p399

[4] Man’s Fight to Fly John Heinmuller Funk & Wagnalls Company p75

[5] Longines through Time, Stephanie Lachat p116

[6] Longines through Time, Stephanie Lachat p116

[7] Quotefancy.com

Living in France. My granddad got an original hour angle time piece during WW2 as payment for goods sold. It’s dated 1934 and has silver casing. Runs fine and I would like to sell it. Condition is very good. Pictures ‘ll be sent if required.

Greetings Erwin and many thanks for your mail. If you have a few pics of the piece that would be super. There must be a colourful story perhaps with your grandad’s acquisition. They can be emailed to andy_timeman@yahoo.com. Many thanks Andy