Lindbergh stated that, “Flying has torn apart the relationship of space and time : it uses our old clock but with new yardsticks”. His miraculous 3620mile Atlantic crossing ended May 21, 1927, and created the so called ‘Lindbergh Boom’.

This was literally an explosion in all things’ aviation – the number of pilots and license holders, a surge in plane orders, passenger miles flown, and the introduction of new aviation routes. It propelled Lindy to be the most famous man in the world.

One of aviation’s greatest playmakers, employee of Longines US agent, and the timer of the Federation Aeronautique Internationale, John Heinmuller, noted that Lindbergh experienced an Atlantic pressure distribution event that accounted for an incredible net wind drift of zero enroute. The unusual weather pattern, a first in recorded history, enabled Lucky Lindy to use dead reckoning to hit the Irish coastline within a few miles of target. Pilotage allowed him to successfully fly onto Le Bourget in Paris.

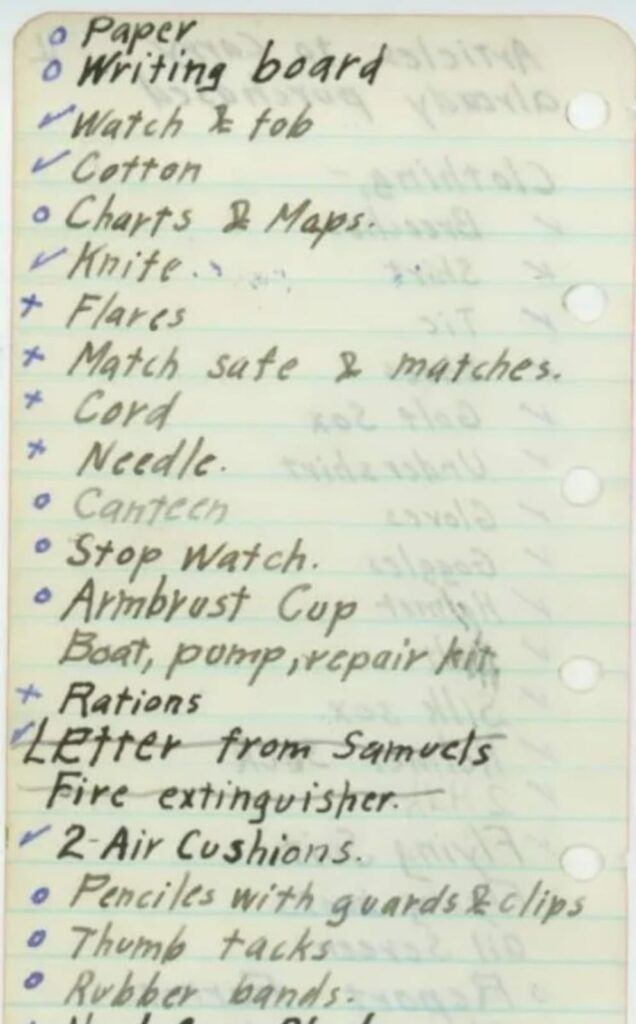

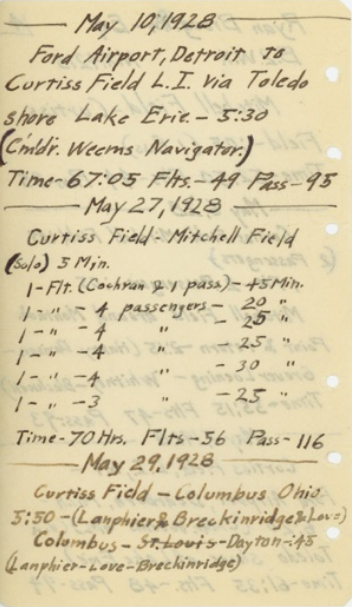

Handwritten notes made by Lindbergh give us some insight into the timepieces that accompanied his record breaking 33hour 39minute flight. He referred to a range of instruments in his preparation notes titled Retail Instrument cost list.

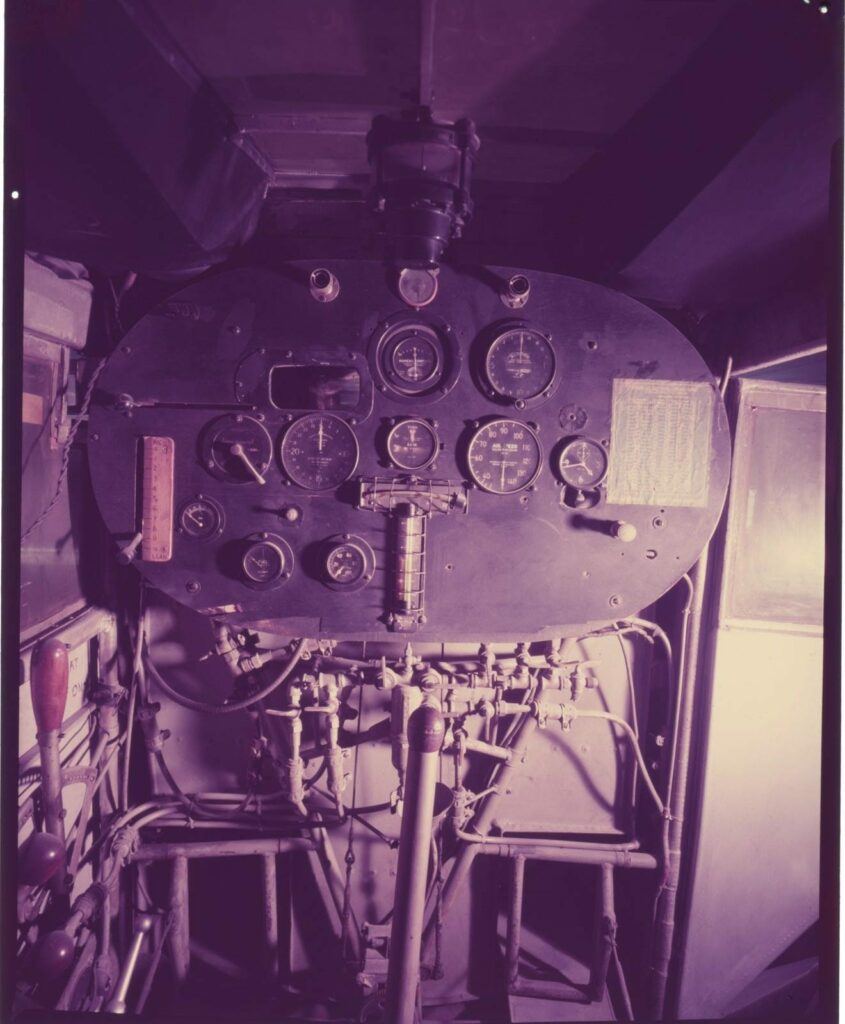

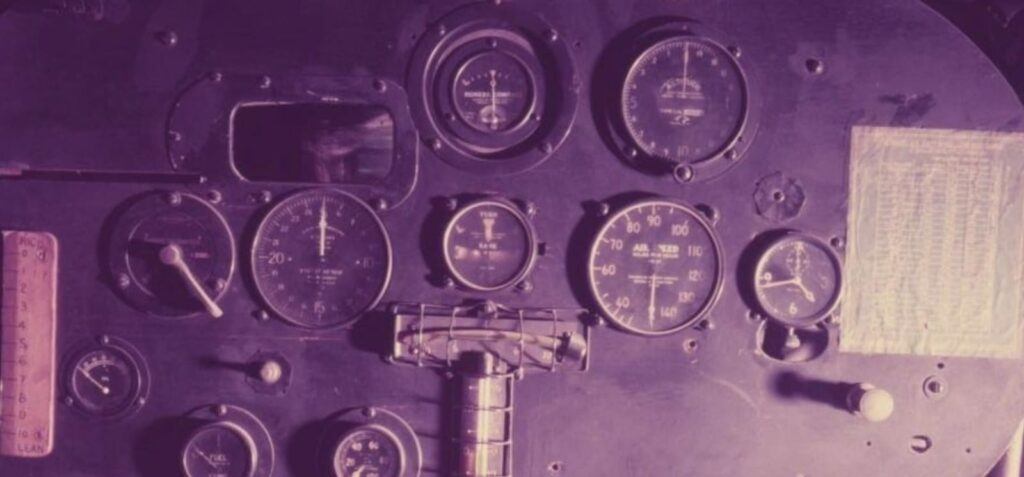

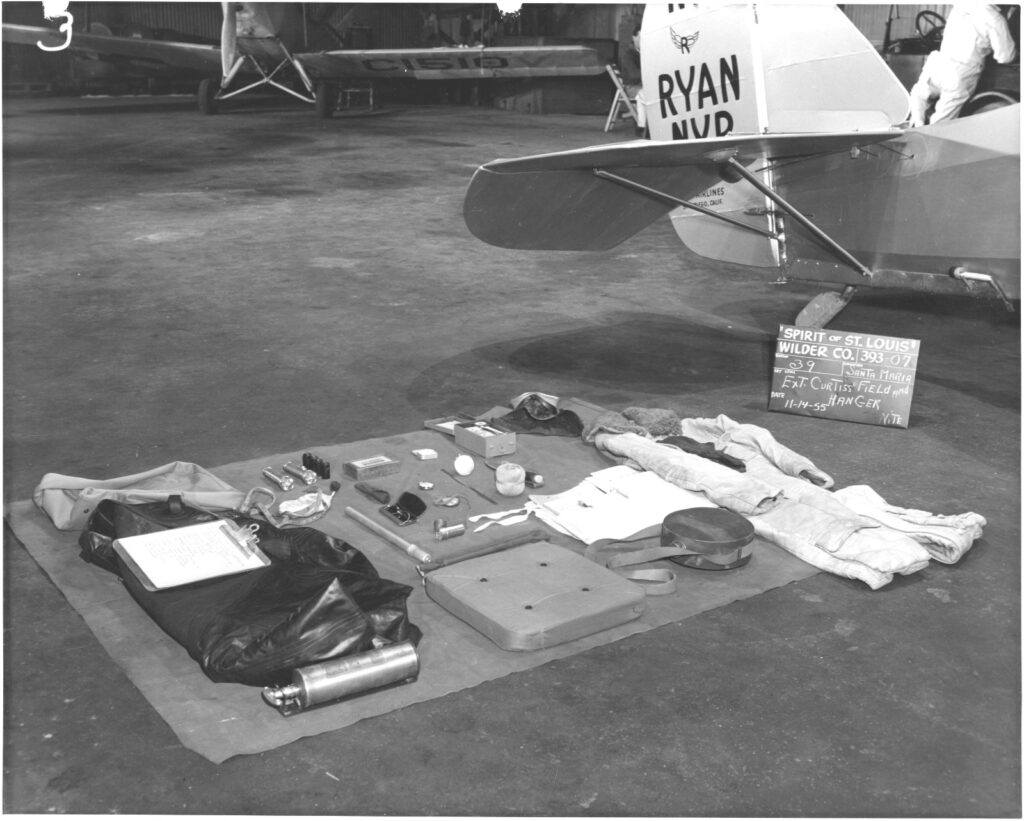

Whilst the clock brand was not noted, priced, nor ticked, we know that the Ryan Air N-X 211 single engine, single seat Spirit of St Louis was fitted with a Waltham 8-day XA model aircraft clock on the instrument panel.

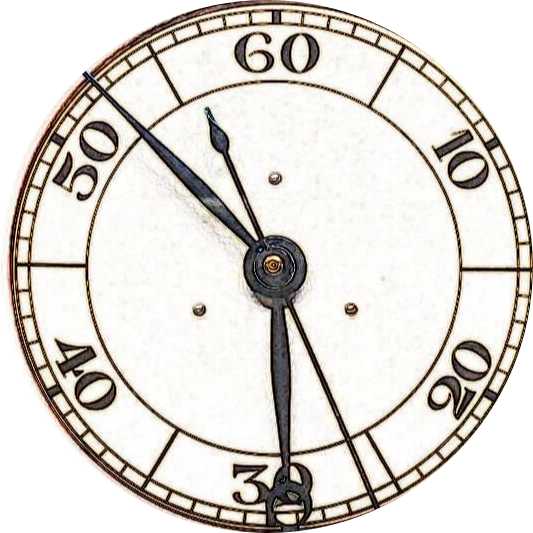

The standard dash mount aircraft clock featured a black dial with oversized luminous 3,6,9,12 Arabic’s with a register at 12 for constant seconds. The clock now lies as an exhibit within the Smithsonian and was donated by Lindbergh on the 30th of April 1928 following his extended nationwide American tour post his Atlantic success.

There is also reference to a Timer noted at $18USD. This is most likely the Pioneer Speedtimer that at first vanished post landing and later reappeared before being donated to the Smithsonian.

On another preflight personal handwritten note page titled Articles to carry already purchased, a watch and fob (ticked) and stopwatch (not ticked) are detailed.

Little is known about the brand or type of either of these personal watches Lindbergh most likely used on his incredible Orteig prize winning Spirit of St Louis record breaking 1927 flight. The note lends substantial support to his accompanying timepiece being a pocket rather than wristwatch.

Initially post WWI two types of navigation were used by pilots to determine their position. The first, pilotage, involved looking out the window using known landmarks to gain bearing. The other dead reckoning involved setting a compass course based on one’s last known position taking account of known speed and drift.

Prior to Lindbergh’s flight, radio navigation was added to the pilot’s bag of tricks allowing a watch to be set and regulated against a known accurate time source. This was made possible post February 1924 after the British Astronomer Sir Frank Dyson developed the famous BBC “pips” or Greenwich Time Signal (GTS) by using two mechanical Royal Observatory clocks.

This led to the development and introduction of air navigation master P.V.H Weems so-called Second-setting watch. The watch enabled the exact second to be set, relative to the hour and minute hands.

The very first two pieces, a Patek and Hamilton were modified postproduction by Mr Dadisman who worked for Jessops Jewellers in San Diego. The Waltham Vanguard pocket watch model was also used prior to the creation of the Longines dedicated second setting production watch. The inner chapter disc on the Longines large Weems could be rotated in either direction to gain an additional accuracy of +/- 30 seconds by using a radio signal or other known exact timepiece. This was later achieved through use of the turning bezel on the so called new second setting models that followed.

The Waltham Vanguard pocket watch with registers at 6 and 12 was one of the watches edited by Weems for this purpose. Pieces were modified postproduction by Mr Dadisman, a specialist watchmaker in San Diego to allow the second setting regulation. This work was later undertaken by Weems, Lindbergh et al.

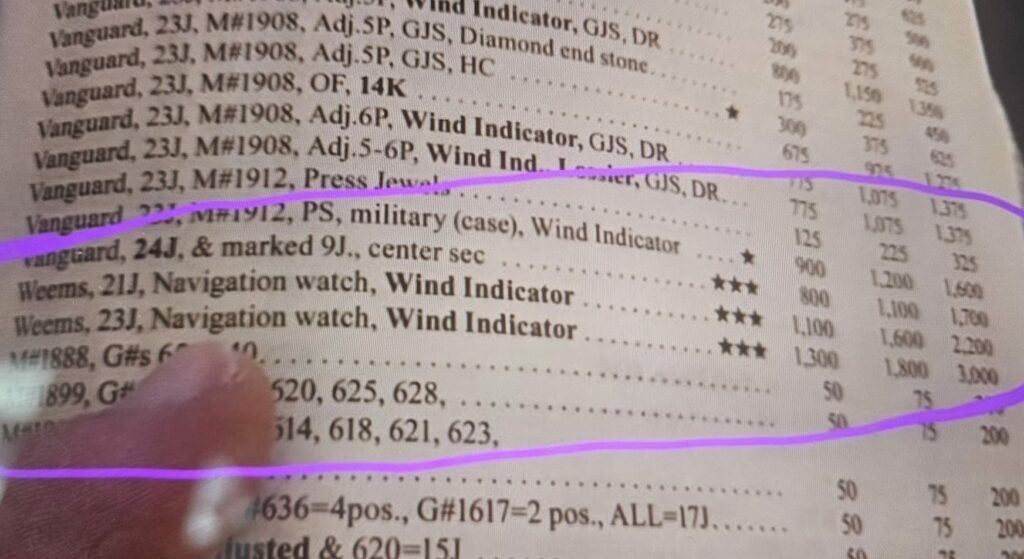

In a vintage watch buyer’s guide, it notes a written description of either a 21 or 23 Jewel version of a Waltham Weems along with a separate captioned picture of one. It serves as a clear reference to the existence and title of the one of the earliest second setting watch models of Weems.

One of these rare Waltham Vanguard Weems in new condition belonging to Lindbergh was donated to the Smithsonian. It is unlikely this was carried on the flight. The other, a well-used example, personally modified by him rests in the Missouri History Museum with its caption noting that it was used by Lindbergh during his record-breaking US transcontinental flight in 1930.

Is there any possibility that this piece was Lindbergh’s earlier companion on the New York to Paris flight?

Whilst Rear Admiral Moffett, who was the chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics for the US Navy Department sung the praises of the Second setting watch by stating, “The suggestion… as to a moveable second-hand dial is considered to be a very valuable one, greatly facilitating the process of keeping a clock set to the exact time.”[1]

There was no radio noted on Lindbergh’s Retail Instrument List. We also know that he had considerable concerns about on-board weight and chose not to take heavy radio navigation gear. Lindbergh’s relationship with Weems came post his 1927 New York to Paris crossing after undertaking additional navigation training with the master.

Further, Admiral Moffet’s statement that appeared in Weems Air Navigation book published in September 1931 was likely made post the introduction of the Longines large 47mm Weems so called Aerochronometer and after expansion in the number of US radio beacons.

The first large Longines Weems all silver prototype and the personal watch of the creator was delivered in November 1928, a collaborative effort involving Wittnauer’s John Heinmuller and the St Imier technical director and wizard Alfred Pfister.

Finally, whilst the Missouri Waltham Weems is a second setting watch it is also crudely hand marked with red numbers that denote the Greenwich Hour Angle and whilst it is likely the first hour angle watch perse it most likely comes late in late 1928 or 1929.

Whilst the second setting and hour angle markings were both likely added to the watch at different times there is an exceptionally slim possibility that the Waltham Weems Vanguard model pocket watch resting in the Missouri museum was in existence in 1927.

It may have a claim to fame, but all evidence points otherwise.

In all likelihood and as noted in his 1927 flight preparation notes, a pocket watch and possibly a stopwatch were used by Lindbergh on his world changing New York to Paris flight. We are still no closer to a definitive answer solving our mystery on the make and type of his personal timepiece.

These remarkable Flightbirds remain at large, and another horological jigsaw puzzle still awaits completion.

[1] Air Navigation Weems 1931 first edition p400