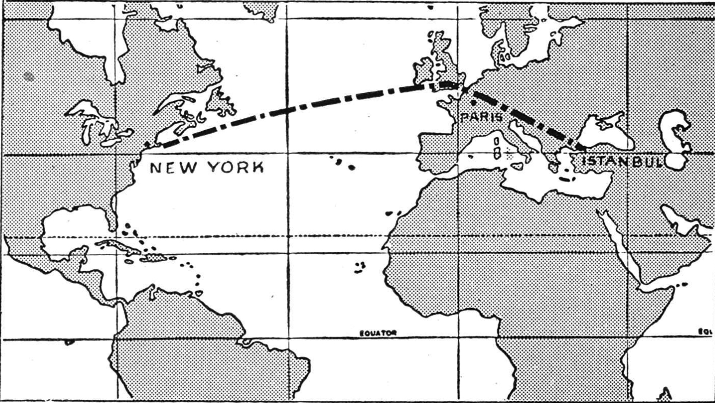

Born in Westfield, Connecticut on January 22nd, 1898, Russell Norton Boardman a member of the Longines Honor Roll, would go on to make an incredible non-stop flight from New York to Istanbul.

This flight would further push at the boundaries of long distance flight in a carefully prepared expedition ‘which [would] yield valuable scientific data and add increment to flying and navigation lore on which progress is built.’ [1]

The Bellanca plane, Cape Cod, carried a load twice its own weight in this epic non-stop flight. Boardman and John Polando were met by cheering crowds in Turkey, to admirers astonished and inspired by what they had achieved. Their record of 5,011.8 miles stood firm for nearly two years.

After two failed attempts the aviators finally left Floyd Bennet Field on July 28th, 1931. Narrowly avoiding disaster in one particular take off, with the heavily fuel laden Cape Cod unable to successfully lift herself into the air.

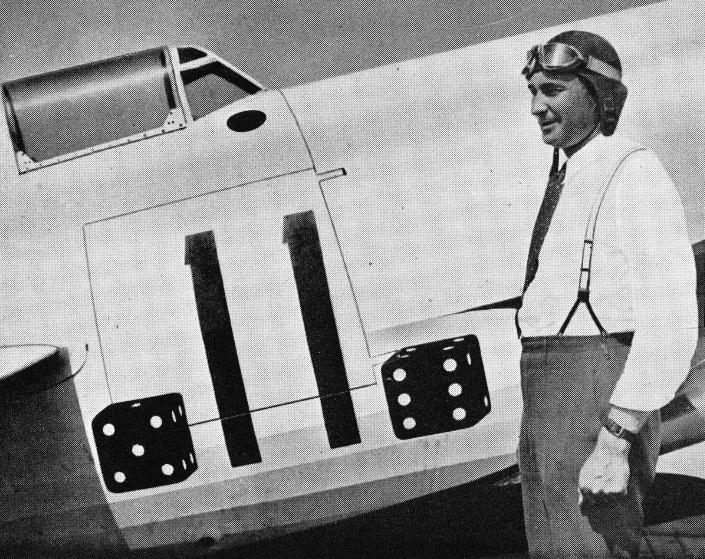

A Bellanca CH-300 Pacemaker

Boardmans’ plane The Cape Cod (Registration: NR761W) was a rebuilt Bellanca called “The American Legion” which was destroyed by fire in October of 1930.

The telephone standards near the airfield had to be removed with Boardman later recognizing that these obstructions could have been the end of them.

They were finally airborne with 50 hours’ worth of fuel on board, far surpassing the recommended weight limit of the aircraft.

They flew through thick fog across the whole Atlantic passage. Observations were impossible with zero visibility and the two men relied on their meticulous preparations and skilled navigation to see them through.

Luckily their ‘artificial horizon, the directional gyro and other instruments and navigational equipment were working perfectly.’[2]

Making it through dense fog onto Paris, Boardman dropped mail, including the latest edition of the New York Times, on Le Bourget airfield.

They spent 6 hours dodging the Alps, failing to distinguish between clouds and mountains in weather that offered no clear visibility. Boardman later wrote ‘We longed for daylight,’[3] as they zig-zagged through valleys and mountain peaks, unsure of their fate.

They almost abandoned the flight through the Szretinye Mountains as, once again, visibility proved impossible.

The clouds slowly lifted and as they resumed their original course, crossing the Balkan Mountains, they were elated to discover the emergence of the Black Sea of Marmora framing the ornate minarets of Istanbul.

Boardman had reached his destination after no small amount of difficulty and uncertainty.

After 49 hours and 8 minutes aboard Cape Cod , Polando and Boardman were met by a cheering crowd in Turkey.

After a long and arduous journey they were greeted by Turkish government officials and an ambassador from the United States.

Everyone congratulated them on this daring and record breaking journey. No one had ever flown so far in one sitting.

Boardman had landed in Istanbul with only 20 minutes’ worth of gasoline left. They really had pushed Cape Cod to her limit and prevailed.

Boardman was no stranger to daring feats of adventure.

He had been employed as motorbike racer and exhibition rider, before moving into the world of aviation. He and Polando had met at a “Wall of Death” motorcycle event where Boardman was employed as a rider.

Like many legendary pilots of the day he initially found aviation work as an aerial stuntman, performing death defying feats in mid-air.

Regularly changing from plane to plane while air borne, wing walking and hopping from moving vehicle to plane during shows that shocked and amazed onlookers.

He even appeared in Howard Hughes WWI epic Hell’s Angels.

Boardman developed a real passion for planes and began a serious study of both aviation and aerial navigation.

He understood how important and crucial air transport would become and found prominence as a highly skilled pilot.

His career was cut short on July 2, 1933 in Indianapolis. During a Bendix Trophy, coast to coast speed race, the skilled pilot crashed during take-off.

He died in hospital from massive injuries. ‘His death shocked the aviation world, and the nation lost a great flier and sportsman who had contributed much to American air supremacy.‘[4]

Within his lifetime, Boardman pushed at the limits of long distance flight.

Feats, such as his record breaking non-stop dash to Istanbul, broadened our understanding of navigation and opened up a world of possibility. Boardman helped to emphasize the limitless opportunities that flight could offer.

Footnotes

- John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘X Russell Norton Boardman and John Lewis Polando,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. 150.

- John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘X Russell Norton Boardman and John Lewis Polando,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. 153.

- John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘X Russell Norton Boardman and John Lewis Polando,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. 153.

- John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘X Russell Norton Boardman and John Lewis Polando,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. 156.

Bibliography

Anonymous, ‘Cape Cod’s Success Climaxes 5 year’s Bellanca Records,’ The Delmarvia Star, Wilmington, Delware, (The Sunday Morning Star, Aug 2, 1931) https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=2293&dat=19310802&id=pM4mAAAAIBAJ&sjid=OgIGAAAAIBAJ&pg=3141,5940038&hl=en

Heinmuller, John P.V. ‘X Russell Norton Boardman and John Lewis Polando,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945).

Hollway, Don. ‘7 & 11’, Aviation History, (World Hisory Group, November 1944), http://www.donhollway.com/doolittle-geebee/7-11.html