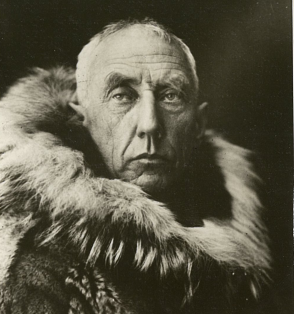

The Last Viking, a name affectionately bestowed upon Roald Engebreth Gravning Amundsen, a fearsome Norwegian explorer who conquered the harsh extremities of both polar regions. Born on July 16th, 1872 in Borge, Norway, Amundsen was welcomed into a family of merchant sea captains.

His mother, anxious that he should pursue a different career from his forefathers, encouraged him into medical school. Soon after she passed away some time after Amundsen’s 21st birthday, he left the medical world for that of Arctic adventure and expedition.

In a drive to map the final unknown corners of the world, Amundsen would go on to find fame and recognition as the first undisputed explorer to reach both North and South Poles. It is only fitting that he is a prominent member of the Longines Honor Roll.

Owing to learned experience, strong leadership, sheer determination and impeccable preparation; he was to traverse a treacherous continent the size of Europe and Australia combined. Antarctica stood as the ever elusive white whale during this heroic age of exploration.

Prior to his infamous South Pole expedition, Amundsen was to establish himself as a prestigious explorer during 1903-1906.

The Northwest Passage

Successfully leading a 70-foot fishing boat through the entire length of the Northwest Passage in Amundsen’s Gjoa; the journey was to be the first of its kind. Hugging the coast in this relatively small ship, the perilous route between the northern Canadian mainland and Canada’s Arctic islands took Amundsen’s crew 3 long years to complete.

Eager to continue exploration of his beloved icy terrain, Amundsen next endeavored to reach the North Pole.

After learning of Ernest Shackleton’s failed attempt Amundsen began a detailed study of his journey in anticipation for his own.

Making meticulous preparations based on Netsilik Inuit survival skills, the crew abandoned heavy wool clothing for animal skins and utilized dog and sled in favor of mechanical snow mobile. This planning was paramount to Amundsen:

I may say that this is the greatest factor—the way in which the expedition is equipped—the way in which every difficulty is foreseen, and precautions taken for meeting or avoiding it. Victory awaits him who has everything in order—luck, people call it. Defeat is certain for him who has neglected to take the necessary precautions in time; this is called bad luck.[1]

Perhaps more than any other Arctic explorer, Amundsen understood the icy lands he traversed. After evaluating previous mistakes during the Belgian Antarctic Expedition (1897–99), learning from the native Inuit population and spending a grueling 3 years sailing the Northwest Passage, he proved especially skilled for the journey ahead.

A Change of Plans

Upon learning in 1909 that American Frederick Cook and Robert Peary had successfully reached the North Pole, Amundsen covertly changed his route.

Leaving Oslo on June 3rd 1910, in the ship Fram (Forward), the crew found themselves destined for the South Pole at Maderia. Having explained this major alteration to his crew a telegram was sent to Robert F. Scott, an Englishman attempting the very same journey, simply stating, ‘BEG TO INFORM YOU FRAM PROCEEDING ANTARCTIC–AMUNDSEN.’[2]

Both Scott and Norwegian supporters hitherto entirely oblivious to Amundsen’s intention, were understandably disgruntled by the news. In light of the covert nature of Amundsen’s expedition, the South race began; with a fizzle rather than a bang.

Upon reaching Antarctica’s Ross Ice Shelf on October 18th, 1911 Amundsen’s crew immediately constructed their Framheim base camp.

Onward to the South Pole

Impeccably equipped and with a large pack of specially bred sled dogs the crew set about creating supply depots at 80°, 81° and 82° South along the Barrier.

These depots were to sustain them, at intervals, throughout the grueling journey to come. The dogs themselves were to become a source of fresh meat throughout the expedition south.

Departing from base camp on October 19th 1911 with four sledges and 52 dogs the team would later arrive at the Polar Plateau on the 21st November 1911 after an arduous 4 day climb.

On the 14th of December 1911, having traveled the previously unknown Axel Heiberg Glacier, the team arrived at the South Pole (90° 0′ S) with just 16 dogs.

Olav Bjaaland, Helmer Hanssen, Sverre Hassel, Oscar Wisting, and Amundsen erected a small tent to mark their accomplishment should they not return to base camp.

Roald Amundsen and Team at the South Pole 1911 – Commemorative Stamp

Affectionately naming the South Pole camp Polheim (Home on the Pole) and renaming the Antarctic Plateau as King Haankon VII’s Plateau, Amundsen declared the site a success for Norway.

Scott’s expedition arrived some 33-34 days later to a small Amundsen erected tent that spelled disappointment. To finally make it all that way and realize defeat was disheartening for the team who subsequently died on the return journey.

The frozen corpses of Scott’s men, along with their journals, were found by a search party eighth months later. They had only been 11 miles away from their own fuel and food depot.

After making their way back without incident to Framheim on January 25th 1912, Amundsen publicly announced his triumphant return on March 7th 1912.

Amundsen went on to sail the MAUD as the second man ever to complete the Northwest Passage around Siberia. After attempting to journey farther North, and failing, he set his sights on aviation.

Onward to Aviation

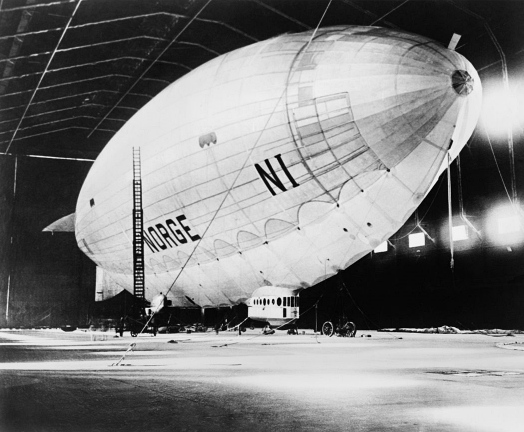

He and Lincoln Ellsworth went on to fly the dirigible, NORGE, from Spitsbergen to Alaska via the North Pole in 1926.

Airship Norge in its hangar before the Amundsen-Ellsworth Transpolar Flight

If Richard E. Byrd’s infamous flight is to be disputed, as it continually has been, then Amundsen’s flight was the first trans-Arctic flight across the North Pole.

There is much controversy concerning who arrived at the pole first. With reportedly inconsistent navigational reports and missing pages within Byrd’s flight log, many claim that he was not the first to reach the pole. If so, then Amundsen would be the first man to reach both the Northern and Southern Polar extremities.

In 1928 Roald Amundsen remarked to a reporter, “If only you knew how splendid it is up there, that’s where I want to die.“[3]

That same year Amundsen died in the Arctic Ocean, his plane crashing into the icy abyss whilst flying with a rescue party to retrieve a fellow explorer.

On June 18th, 1928 the Arctic claimed his life. Various pieces of Amundsen’s French Latham 47 flying boat were later found near the Tromsø coast. After an extensive search his body was never found.

Footnotes

- Roald Amundsen, The South Pole: An Account of the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition in the ‘Fram,’ 1910–1912, (New York, Cooper Square Press, 2001) pp. 222.

- Paul Simpson-Housley, (1992). Antarctica: Exploration, Perception and Metaphor. (Routledge, 1992), pp. 24–37.

- Roland Huntford, Scott And Amundsen: The Last Place on Earth, (London: Hachette UK, Sep 13, 2012), pp. 540.

Bibliography

Amundsen, Roald. The South Pole: An Account of the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition in the ‘Fram,’ 1910–1912, (New York, Cooper Square Press, 2001) pp. 222.

Huntford, Roland. Scott And Amundsen: The Last Place on Earth, (London: Hachette UK, Sep 13, 2012), pp. 540.

Simpson-Housley, Paul. (1992). Antarctica: Exploration, Perception and Metaphor. (Routledge, 1992), pp. 24–37.