Born in 1910, Publio Magini would become instrumental in one of the biggest covert operations of World War II. This extraordinary Italian mission bore witness to mystery, danger and intrigue as Magini attempted to ferry secret codes between Rome and Tokyo.

Under the fascist dictatorship of Benito Mussolini, Italy aligned itself with Axis forces. A partnership with Germany and Japan was formed, with Mussolini holding more in common with Hitler’s ideology than that of the democratic Allied forces.

At the beginning of 1942, Italian forces became suspicious of British and American intelligence. Convinced that the Allies were cracking secret radio codes used for communication with Japan, the desperate need for a new system of coding was realized.

All future transmissions would be compromised if not for the creation of a specialized air link between Germany and Japan. The mission ‘had to be conducted in secrecy, and it was shrouded in lies, to serve the interests of the governments involved.’[1]

Travel by sea was not a viable option; it would take a submarine some two months to reach Japan and a boat would move at a similar pace with a far heightened chance of interception.

The only way to safely ferry codes was by air; over unknown lands and amidst an ominous rumor ‘that one of the new four-engine Condors, a long-distance German aircraft, had disappeared while trying to deliver codes from Germany to Japan.’[2]

The distance between the two countries was a daunting feat in itself for early aviators, never mind the added danger of being obliterated by enemy fire mid-air.

The Plan for Success

The Regia Aeronautica Italiana (Italian Royal Air Force) employed the services of Magini; a dedicated aviator, technician and navigator especially skilled in blind flight. Magini was already recognized as one of Italy’s best pilots before the outbreak of World War II and the Italian Royal Air Force was to rely heavily on his skill and navigational expertise.

The flight was dangerous, with the ever looming threat of enemy fire alongside destabilized territories and air space. Nevertheless, Magini was prepared to make the journey.

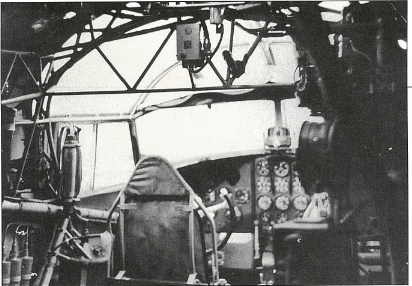

Unable to rely on radio guidance over the Soviet Union, Magini understood how crucial proper flying instruments were to the success of such a flight. Magini searched for the perfect instrument to guide his crew along his elaborately devised flight plan. A precise system of astronomical navigation was crucial to the success of this dangerous mission.

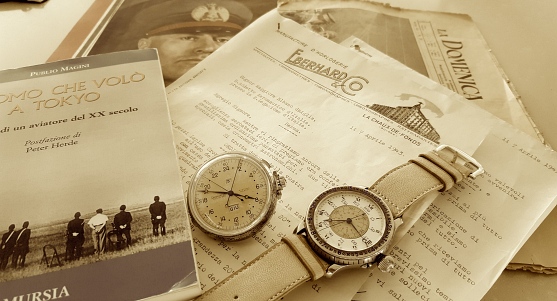

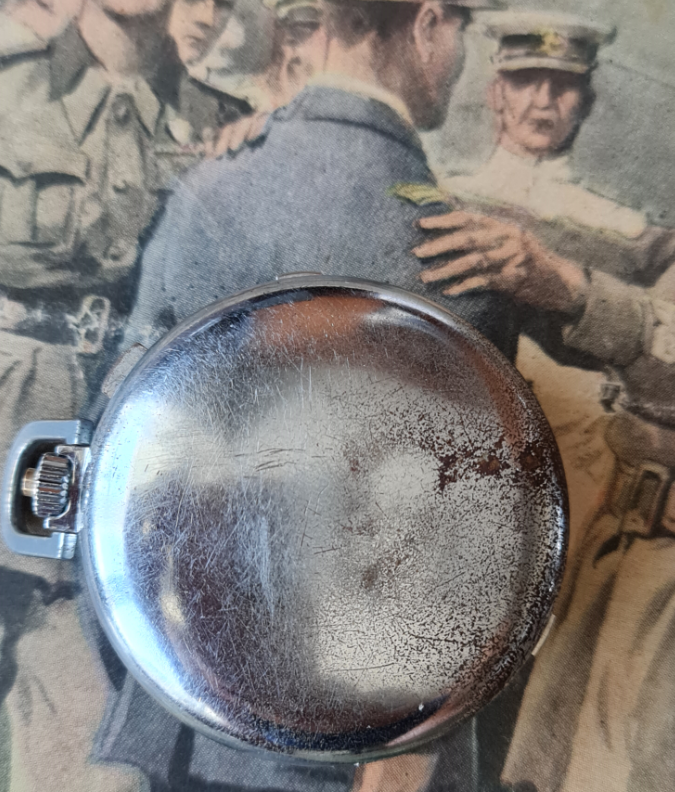

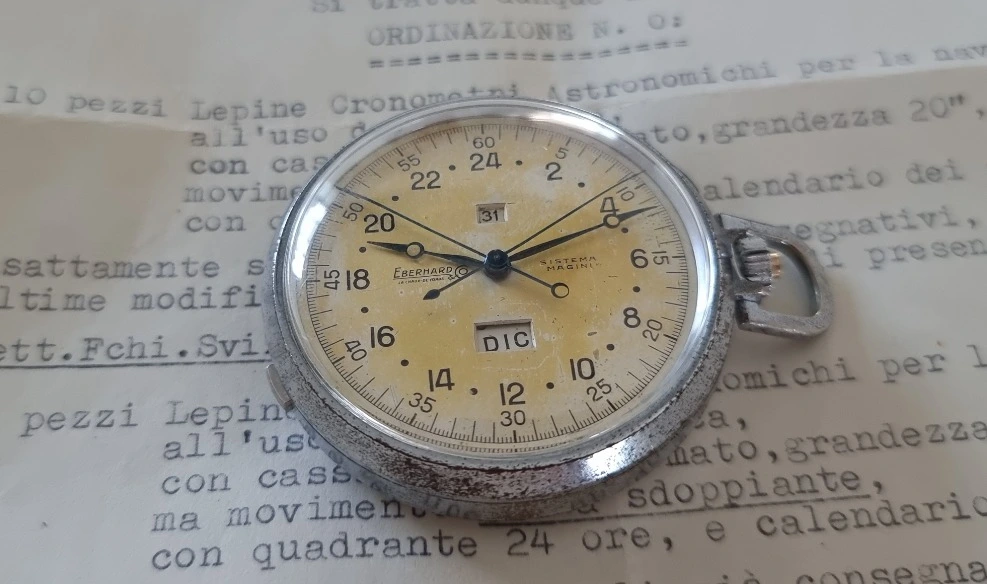

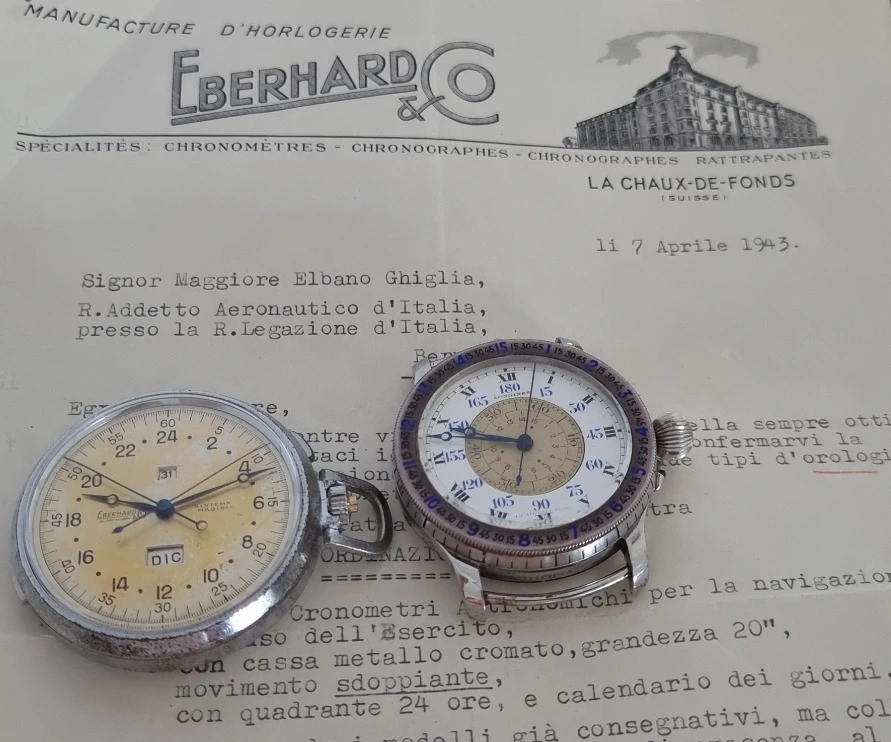

Magini employed the services of two extraordinary time pieces for the journey; the Longines Hour Angle wristwatch and a unique split-second chronograph pocket watch manufactured by Eberhard.

The Hour Angle was a state-of-the-art aviator’s watch that improved up P.V.H Weems second setting watch. The model designed by Lindbergh, added calibrations for the unit of arc on a turning bezel and allowed and expedited the calculation of longitude.

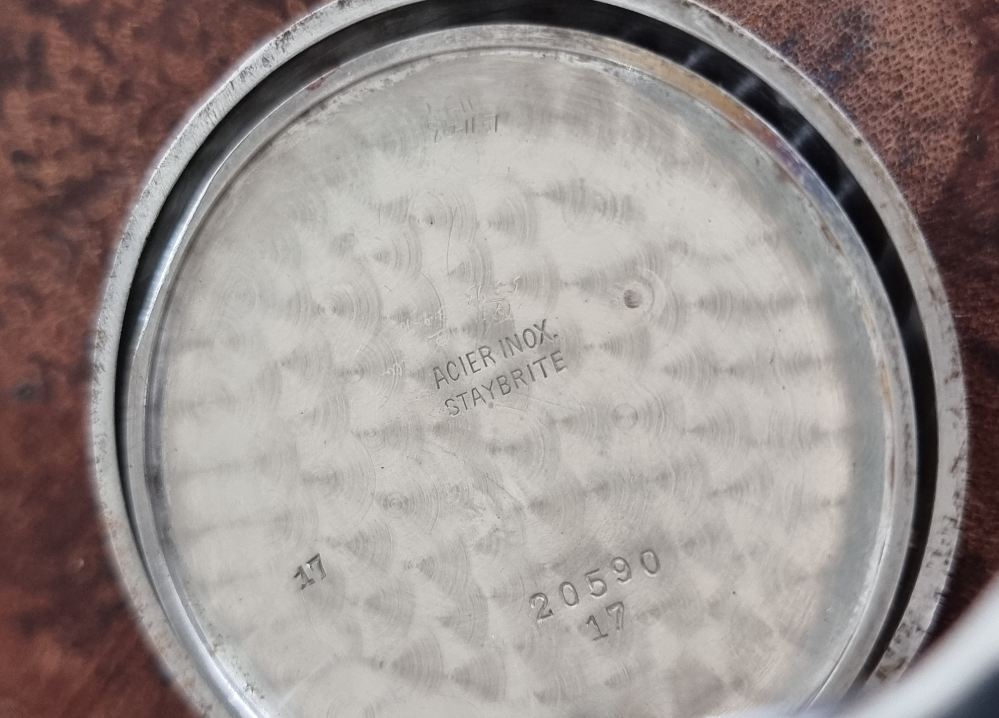

Archives note the Italian company Ostersetzer received order 20590 for a handful of ref 3210 stainless steel hour-angle pieces, all using the robust 18.69N pocketwatch calibre.

Antonio Cairelli, was an intermediary and the military supplier of the Regia Aeronautica, and his name was printed in red at the six o’clock position by Longines and noted in their archives. The order was invoiced on November 18, 1939. To date, just three of these A.Cairelli signed Lindberghs have surfaced.

It was ‘the only watch capable of meeting the requirements of pilots during long distance flights [with a] dial [that] permits the direct reading of the hour angle of Greenwich.’[3]

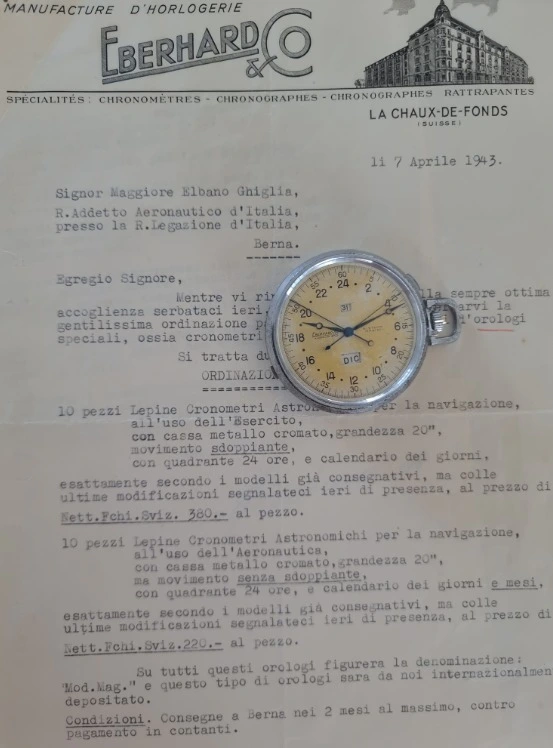

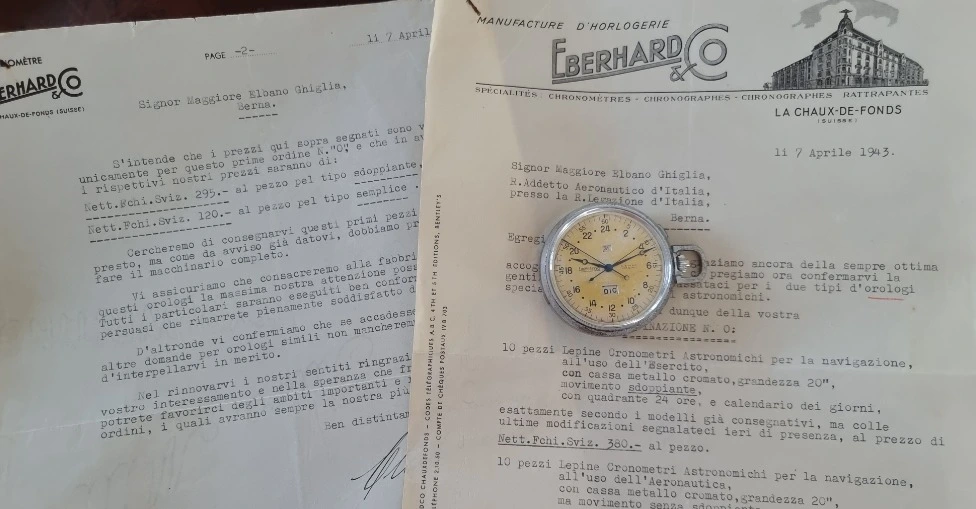

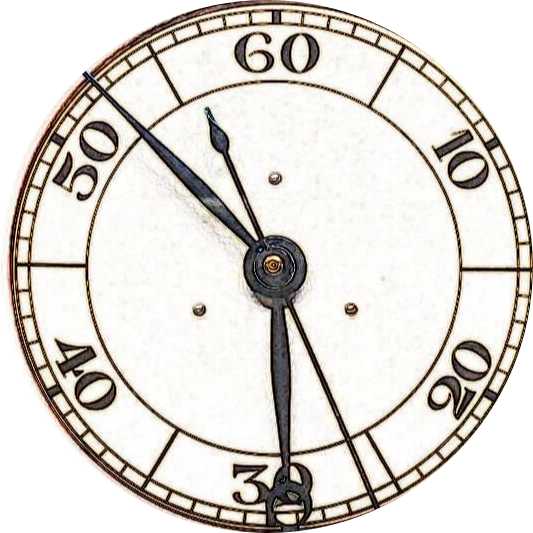

The 24-hour split-second chronograph by Eberhard & Co. was specifically designed for Magini’s flight, allowing ‘pilots to measure intermediate times without interrupting the timekeeping of the entire mission.’[4]

The pocketwatch dial carried the words Sistema Magini. The original purchase order from Eberhard notes an order for 10 pieces, however, due to the Mussolini’s replacement and the cessation of the war shortly later, just a single piece was delivered.

Both time pieces were to accompany a truly extraordinary journey.

A Test Flight

In order arrive safely in Tokyo, their plane would need to be heavily loaded with the necessary fuel. This would mean flying low for 15 hours, increasing their visibility to any aircraft occupying the same space. It would also make navigation extremely difficult.

Flying low often mean flying under cloud cover with cracks of sky breaking through the clouds at unpredictable intervals. Magini remarked, ‘if I could see only one star, I had to be sure what star it was, make the proper observation, and fix our position.’[5]

Magini, having never flown this flight path, had no idea of the sort of winds they would face. In light of these circumstances the plane had to be loaded with all the fuel it could carry. All necessary weight was discarded, with the crew carrying nothing but their flight suits; even the seats were removed in favor of light canvas constructions.

A test flight from Rome to Asmara, Ethiopia was arranged for May 7th, 1942, expecting to arrive on May 9th. This date would mark the Italian anniversary of the conquest of Ethiopia. Despite having lost Ethiopia one year prior, the Italian Authorities felt this a fitting tribute to this strange anniversary. Magini, however, found it ridiculous.[6]

Captain Amedeo Paradisi, Ezio Vaschetto, Vittorio Trovi and Magini set off from Guidonia Airport on May 7th, landing at Benghazi about 5 and a half hours later. They spent the night and refueled the aircraft before completing the final leg of the journey.

The crew arrived in Asmara at 3.A.M. on May 9th in time to commemorate the anniversary as per ordered. From Asmara they flew straight back to Rome without pause for about 28 hours, arriving at Ciampino airfield exhausted and successful.

After a well-deserved night’s sleep Magini received a call ordering the crew to transport the plane to Guidonia only a few miles away. Such a short journey was by no means daunting to the men who had just flown on of the longest flights ever made by the Italian Airforce.

However, immediately after take-off, all three engines failed and the plane fell from the sky in a devastating crash. The aircraft was ablaze as Magini, got out from the cockpit, climbed over the airplane, and jumped down, hitting a boulder and injuring my leg.

‘I went back to the airplane from the rear and pulled out Paradisi whose leg was badly gashed. The two of us barely got away before the plane exploded’.[7]

Paradisi lost his leg and Magini spent a month in hospital with his leg in a cast. Despite this, the Rome- Tokyo mission was still a go. A new crew was selected and awaiting Magini’s hospital release.

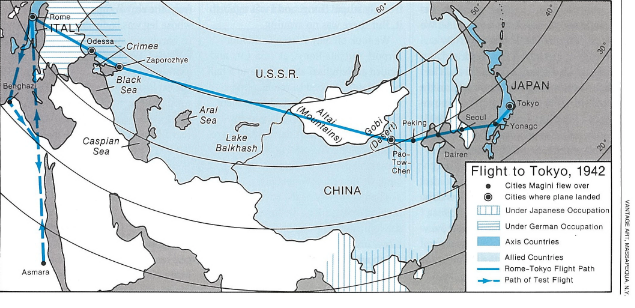

The Planned Route

In anticipation of this new crew Magini began to prepare navigational charts and maps. He was dismayed to discover that no such maps existed of the Gobi desert. This vast unknown expanse was a mystery to all and posed a real threat to the crew. However, orders were orders and Magini was forced to overlook this potential difficulty.

He planned two stops, the first in German held Ukraine at Zaporozhye, and the second in Japanese occupied China at Pao-Tow-Chen. Magini’s preparations were somewhat complicated by strict instructions from Japan in that they ‘insisted absolutely nothing must indicate the airplane was headed for Japan – or, on the return trip, that it had been there.’[8]

Magini was also instructed to avoid flying over the Soviet Union due to a neutrality pact forged between Japan and the U.S.S.R. Political tensions would continue to complicate their flight throughout the duration.

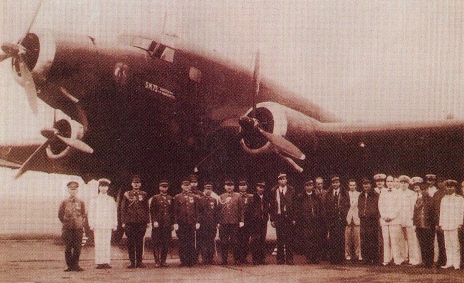

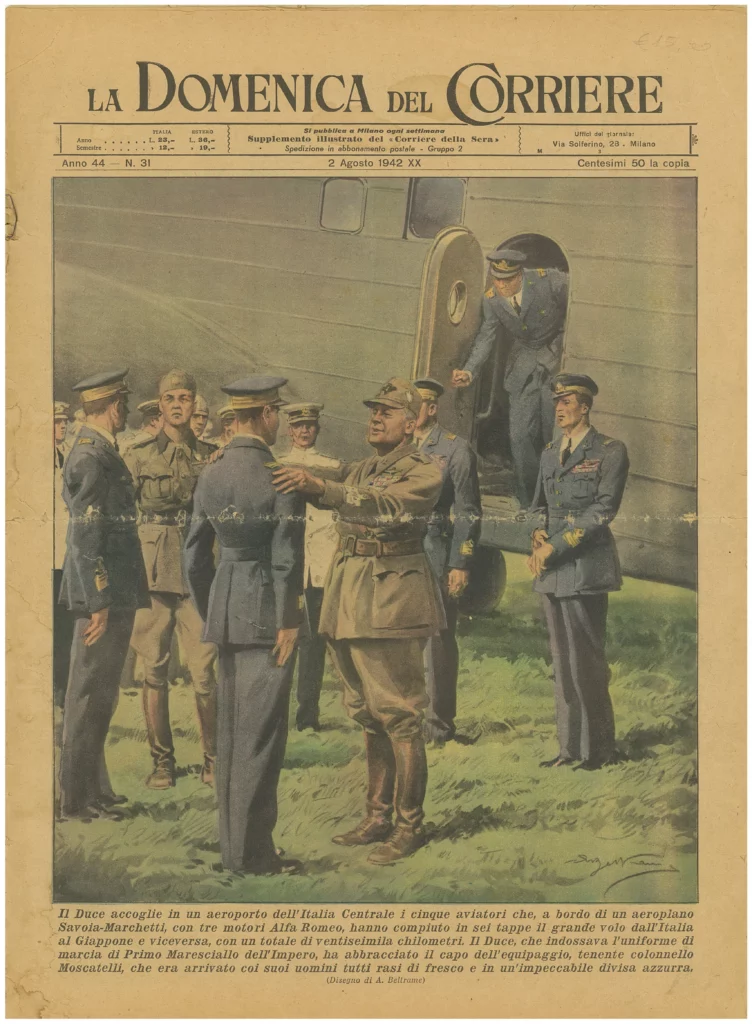

The final Tokyo flight was manned by Antonio Moscatelli, Captain Mario Curto, Lieutenant Ernesto Mazzotti, Lieutenant Ernest Leone and Publio Magini.

Their tri-motor Savoia- Marchetti 75-GA set off from Guidonia on June 29th, 1942 at 5.26A.M. They landed Zaporozhye at 2.10P.M. the very same day without any mishap. Here they waited until the cover of night, taking off again on June 30th, 8P.M.

They flew near the conflict in Rostov, a battle for territory between the Germans and Soviets raging below. Magini recalls:

We knew that we were in great danger. With all that fuel we were unable to climb higher than about 2,500 feet. The airplane, which weighed about 47,000 pounds, was flying very slowly, even at maximum power. The engines were threatening to overheat, we anxiously watched the temperature going up. And now we began to see searchlights everywhere.

At a certain point, we had to decide to cross the front. There was no going back now. As we flew over, searchlights suddenly fastened onto our airplane, turning the night sky into day and making us an easy target. We could not escape those lights.

‘Then from my seat, I began to see antiaircraft shells rising through the shafts of light. They came slowly, but straight at us. It was not at all pleasant. Although they passed close by, not a single shell hit us. I couldn’t believe our luck’.[9]

They flew under fire for some 100 miles before escaping blinding searchlights and imminent danger. Magini was relieved to look upon the Caspian Sea, Aral Sea, and Lake Balkhash. ‘it was a fantastic feeling to have all Asia in front of us, to be so alone at last.’[10]

They traversed the Altai mountain range as the morning sun rose, dangerously close to the border between China and the Soviet Union, before flying over the unknown lands of the Gobi desert. Lying at the edge of the Gobi, they aimed for Pao-Tow- Chen, West of Peking and close to the Yellow river. They passed Pao-Tow-Chen and were instructed by Japanese officials, via radio, to fly back.

To Repaint the Plane at Pao-Tow-Chen

Security restrictions imposed by Japanese forces left the crew no choice as ‘fighters patrolled the home islands day and night, ready to shoot down any airplanes without the Japanese insignia on the wings and rudder.’[11]

A repaint of their Italian plane was crucial, lest they be shot down by Japanese forces.

The landing was no simple task. They encountered torrential rainstorms, lightning and zero visibility as the pilot attempted to dodge fatally hidden hills. After an arduous 21 hour flight, they eventually landed at Pao-Tow-Chen on the 1st of July.

The exhausted crew were offered a warm welcome by both Japanese and Italian officials. They stood ‘still in our flight suits, listening to Japanese generals saying things we didn’t understand.’[12]

The crew were then offered Kimono’s by Japanese Geisha, before being ushered into a large bathing pool. There, they were bathed in hot water by the women before being obliged to stay for a day in anticipation of a correct flight path to the home islands.

Security restrictions meant these flight paths changed daily ‘and if you approached at the wrong time or altitude, or on the wrong course, you would be shot down.’[13]

Their plane was repainted with the Japanese rising sun in order to ensure safe passage before taking off from Pao-Tow-Chen on July 3rd for the last leg of the Journey to Tokyo. The crew were accompanied by a Japanese pilot and ‘as we approached the home islands, he began to give precise directions, without explanation.’[14]

Arrival in Japan

They followed this flight path onto Tokyo where they landed, some 1,800 miles later at 5P.M. on July 3rd. A large group was there to meet the crew as they passed their large sealed envelope, the contents of which are unknown, to awaiting officials from the Italian Embassy.

Magini and his crew stayed in Tokyo for 2 weeks and they were continually forced to lie about the details of their route. Under strict instructions to stay silent in regards to their Soviet Union crossing Magini was left to devise an alternative flight path which, was of course, a fabrication.

Magini recalls that ‘since I was the navigator, I was responsible for explaining to the top people in the Japanese air staff how we had gotten to Tokyo. I was forced to pretend that we had not followed the northern route but a southern one – which was impossible, simply because it would have taken so much longer.’[15]

The Japanese marveled at a flight made using practically no fuel and Magini suspected that they knew he was lying.

However, of all the hardship and difficulty Magini faced; the storms, zero visibility, gun-fire, sleep deprivation, lack of plane seats and the tense lies around their route, he maintained that a borrowed suit was the most uncomfortable experience of his life.

Having only brought his flight suit, due to weight restrictions, he had nothing whatsoever to wear during his stay. An Italian friend offered him a pink suit and ‘never in my life had I felt so uncomfortable. Pink silk – can you believe it?’[16]

A Rapid Departure

Despite the attire, the situation in Tokyo was to become increasingly difficult. Tensions mounted as the Japanese grew inhospitable before asking the Italian crew to leave the following morning. This left them little time to prepare and they were forced to stay awake through the night to make their rushed arrangements.

Magini, once again, ushered the crew, to Pao-Tow-Chen where they received an icy reception devoid of Geisha girls and hot baths. The Japanese repainted the plane to its original design before sending them on their way on July 19th.

Magini and crew fought against strong winds that pushed against the plane for the duration of the homeward bound flight. Their airspeed was worryingly low over the Gobi desert, Magini knowing that crashing would mean certain death: ‘If we went down in that desert, we were as good as dead. Who would ever find us?’[17]

Adding to Magini’s worry, their pilot became ill. Moscatellli handed the controls over to Magini for the duration of his recovery as Magini suffered through violent storms over the Altai range whilst passing from China to the Soviet Union.

Turbulence and lightning ensued as Magini struggled to keep the plane airborne. A lightning bolt hit their radio antennae, obliterating it, turning the radio into useless dead weight.

They crossed Soviet Asia in the dead of night as Magini struggled to peer through thick clouds for a celestial fix. The clouds remained unbroken and a ground fog made it impossible to even get a vague estimation of where they were. Only compass instruments aided the journey as Magini guessed wind conditions.

To add insult to injury, the plane began to climb higher after extensive fuel use; an increase in altitude was evident as a loss of oxygen became apparent to the crew. In the realm of navigation, it really couldn’t have been worse.

Pit Stop at Odessa

Magini rerouted to Odessa in order to avoid the fierce battle being waged around Zaporozhye. Their landing at Odessa was fraught with difficulty before eventual elation upon touch down.

The fog was so thick that we didn’t know whether we would hit other airplanes. We shut down the engines, but their noise went on in our ears for what seemed like minutes. Then, opening the small door, we jumped onto the field, lay down in the grass, and didn’t move. We didn’t say a single word to one another. We were giddy. The smell of the grass was inebriating.[18]

Magini was met by a truck of Germans greatly angered by their unannounced arrival. Upon assurance that Mussolini was to meet them in Rome, the Germans refueled the plane and repaired their antennae. They left, for the final leg of the journey, at 11A.M. on July 20th and arrived in Rome at 5.50P.M. that same day.

Finally Rome

The crew received a tremendous welcome after handing over a box given to them in Tokyo. Mussolini, along with German and Italian high officials congratulated their success and an official ceremony was held in their honor.

Magini, however, felt that something was amiss during the festivities. He recalls that ‘something about it left a sour taste. It took place at the hospital where Paradis was recuperating after the amputation of his leg. He stood through it all on his crutches, pallid and sweating from pain.

Mussolini pinned silver medals for gallantry on the five of us. I’m always a little embarrassed when I think about that medal, because the flight was part of my job. Other colleagues in the war went through more than we did.’[19]

Just five days after their landing in Rome, the crew were invited to a celebratory luncheon at the Japanese Embassy. Characteristic of their dealings with Japanese officials thus far, they were ordered to leave half way through the meal as their true flight path was publicized during the meal. Magini would never again set foot in the Japanese Embassy.

Magini’s mission was to prove especially unique. Just one year later Mussolini was overthrown and the war ended. Their mission was the first, and the last, transportation of code during the war. Years later the Japanese still maintained that the flight did not happen; that it was an Italian fabrication.

After enjoying a long career as an aviator and navigator, Magini went on to work at Boeing representing them in Europe. He also taught physics, participated in underwater archaeological expeditions, and set up an Italian radio network before passing in 2002 at age 83.

His astonishing WWII flight, shrouded in secrecy, danger and intrigue is by no means forgotten. The tangible reality of this flight exists today in the two time pieces that accompanied this incredible war time spy mission.

The journey, pictures of the watches, and the successful covert mission of one of Italy’s most famous war time heroes, Publio Magini, in the Savoia-Marchetti S.M.75 are captured in an Italian book titled “L’Uomo che volo a Tokyo”.

Incredibly a pair of watches that had remained together from 1942, successfully completing one of Italy’s most daring spy missions, were separated in 2002. The watches auctioned in the early 2000’s were sold as consecutive lots, ending up with two different owners.

They spent the next 13 years apart, then reunited, and later sold at Phillips Geneva auction in 2015. The remarkable pair of WWII military flightbirds are an Italian military aviation horological treasure used on a special spy mission. Arguably, the most famous pair of Italian military watches in history, live on, to tell Publio Magini’s extraordinary tale.

Footnotes

- Publio Magini, as told to Anne Crudge, ‘Experience of War. Secret Mission to Tokyo.’ MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History, Vol 5. No.4, (MHQ Inc. New York, 1993) pp. 98.

- Publio Magini, as told to Anne Crudge, ‘Experience of War. Secret Mission to Tokyo.’ MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History, Vol 5. No.4, (MHQ Inc. New York, 1993) pp. 98.

- Nathalie Monbaron, ‘The Geneva Watch Auction: TWO,’ PHILLIPS, (Geneva Auction: 7 & 8 November 2015 6:30pm), https://www.phillips.com/detail/NoArtist/CH080515/146 (date accessed: 28/09/16).

- Nathalie Monbaron, ‘The Geneva Watch Auction: TWO,’ PHILLIPS, (Geneva Auction: 7 & 8 November 2015 6:30pm), https://www.phillips.com/detail/NoArtist/CH080515/146 (date accessed: 28/09/16).

- Publio Magini, as told to Anne Crudge, ‘Experience of War. Secret Mission to Tokyo.’ MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History, Vol 5. No.4, (MHQ Inc. New York, 1993) pp. 98.

- Publio Magini, as told to Anne Crudge, ‘Experience of War. Secret Mission to Tokyo.’ MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History, Vol 5. No.4, (MHQ Inc. New York, 1993) pp. 99.

- Publio Magini, as told to Anne Crudge, ‘Experience of War. Secret Mission to Tokyo.’ MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History, Vol 5. No.4, (MHQ Inc. New York, 1993) pp. 99.

- Publio Magini, as told to Anne Crudge, ‘Experience of War. Secret Mission to Tokyo.’ MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History, Vol 5. No.4, (MHQ Inc. New York, 1993) pp. 99.

- Publio Magini, as told to Anne Crudge, ‘Experience of War. Secret Mission to Tokyo.’ MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History, Vol 5. No.4, (MHQ Inc. New York, 1993) pp. 101.

- Publio Magini, as told to Anne Crudge, ‘Experience of War. Secret Mission to Tokyo.’ MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History, Vol 5. No.4, (MHQ Inc. New York, 1993) pp. 101.

- Publio Magini, as told to Anne Crudge, ‘Experience of War. Secret Mission to Tokyo.’ MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History, Vol 5. No.4, (MHQ Inc. New York, 1993) pp. 101.

- Publio Magini, as told to Anne Crudge, ‘Experience of War. Secret Mission to Tokyo.’ MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History, Vol 5. No.4, (MHQ Inc. New York, 1993) pp. 101.

- Publio Magini, as told to Anne Crudge, ‘Experience of War. Secret Mission to Tokyo.’ MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History, Vol 5. No.4, (MHQ Inc. New York, 1993) pp. 101.

- Publio Magini, as told to Anne Crudge, ‘Experience of War. Secret Mission to Tokyo.’ MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History, Vol 5. No.4, (MHQ Inc. New York, 1993) pp. 101.

- Publio Magini, as told to Anne Crudge, ‘Experience of War. Secret Mission to Tokyo.’ MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History, Vol 5. No.4, (MHQ Inc. New York, 1993) pp. 102.

- Publio Magini, as told to Anne Crudge, ‘Experience of War. Secret Mission to Tokyo.’ MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History, Vol 5. No.4, (MHQ Inc. New York, 1993) pp. 102.

- Publio Magini, as told to Anne Crudge, ‘Experience of War. Secret Mission to Tokyo.’ MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History, Vol 5. No.4, (MHQ Inc. New York, 1993) pp. 102.

- Publio Magini, as told to Anne Crudge, ‘Experience of War. Secret Mission to Tokyo.’ MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History, Vol 5. No.4, (MHQ Inc. New York, 1993) pp. 103.

- Publio Magini, as told to Anne Crudge, ‘Experience of War. Secret Mission to Tokyo.’ MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History, Vol 5. No.4, (MHQ Inc. New York, 1993) pp. 103.

Bibliography

Magini, Publio. as told to Crudge, Anne. ‘Experience of War. Secret Mission to Tokyo.’ MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History, Vol 5. No.4, (MHQ Inc. New York, 1993).

Monbaron, Nathalie. ‘The Geneva Watch Auction: TWO,’ PHILLIPS, (Geneva Auction: 7 & 8 November 2015 6:30pm), https://www.phillips.com/detail/NoArtist/CH080515/146 (date accessed: 28/09/16).

Many thanks, really, from Publio

Magini ‘s son. Sincerely, Leonardo Magini

Dear Leonardo.. apologies for the belated reply as I have been travelling. A big thank you for the feedback and you had a remarkable father. Andy 😉

This is one of the best articles, really enjoyed the reading!

Seiji.. as always a big thank you for your feed back. If only a few love the history it still makes it all worthwhile. Andy 🙂