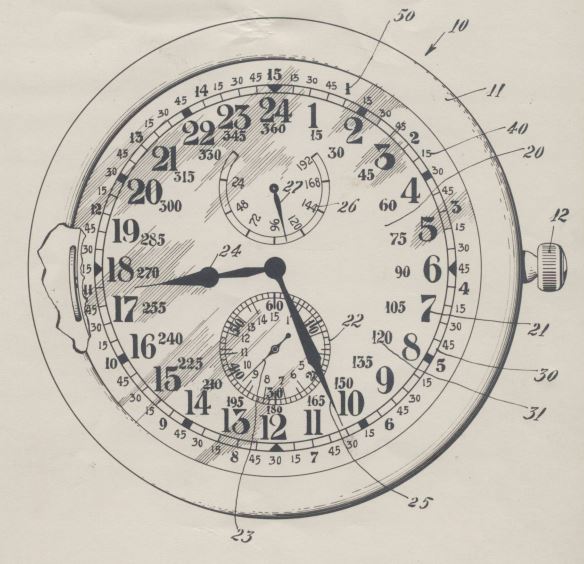

In his article, ‘Possibilities of an Adjustable Rate Clock,’ Weems noted that ‘aerial navigation has not yet ‘arrived’ in the sense that it is either fast or accurate”[1]. Within this, he outlined a multiple independent movement ‘adjustable rate clock’ which would aid in the determination of the hour-angle in aerial navigation.

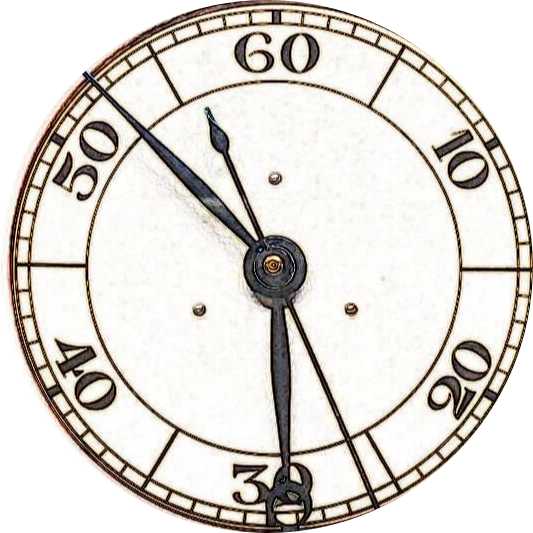

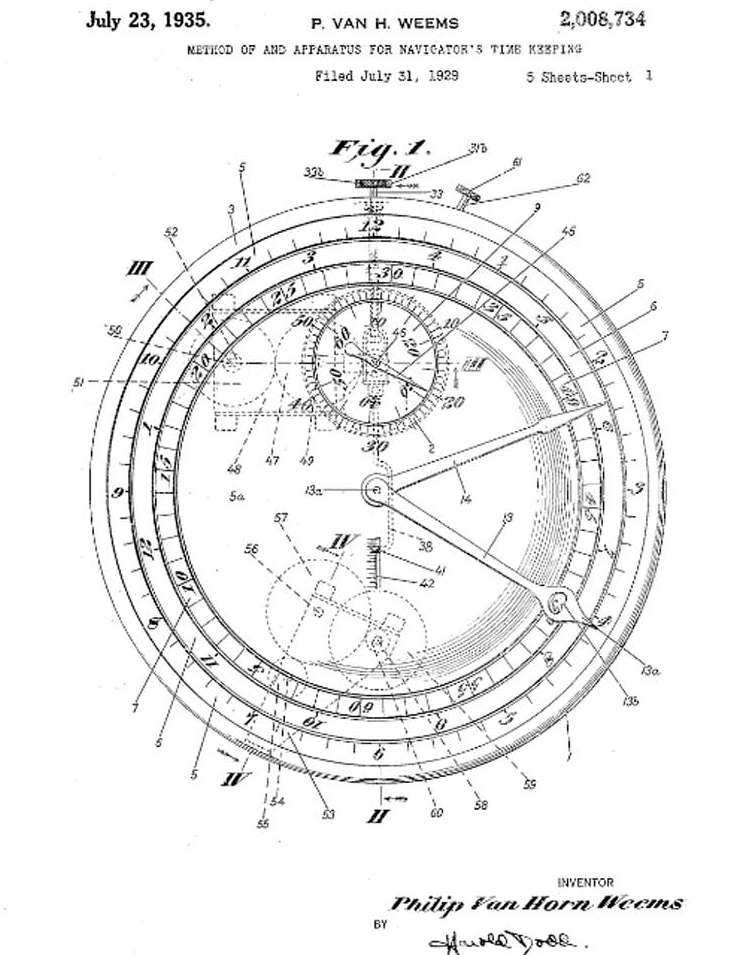

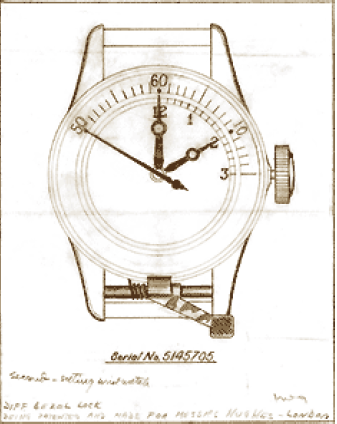

A drawing of Weems proposed Adjustable-rate clock from 1928. The complex multi movement timepiece was not possible to make. The second-setting function that formed part of the adjustable-rate clock was used on the large Longines Weems and patent 2008734 with respect to the second setting was approved six plus years later in 1935.

He noted that “either we must develop faster and more accurate methods of finding the hour angle and the observed altitude, or change to an entirely different system of aerial navigation..”.[2] This timepiece proposed by Weems in the July 1928 article was far too complex to produce.

Lindbergh’s innovative solution arrived two years later in the form of the Longines Hour-angle. The unit of arc calibrations were first incorporated into his aircraft calotte, then featured on the dial of a second-setting watch, before the creation of an oversized specialist aviator’s wristwatch.

It was the worlds very first calibrated turning bezel wristwatch that featured the unit of arc markings to facilitate and expedite the calculation of longitude.

Its predecessor, the second-setting watch, was brought to life after the Commander of the Aircraft Squadrons Battle Fleet gave the navigation master “permission to make some experiments on two torpedo-boat watches. One Hamilton watch rated to mean time, and one Patek Philippe & Cie. watch rated to sidereal time were altered to permit the exact second to be set”[3]. This formed part of Weems’ proposed ‘adjustable rate clock.’

Early 1930’s Longines vintage Weems Second-setting watch (L) and the first-generation production Hour-angle watch (R) designed by Lindbergh with the world’s first calibrated rotating bezel that arrived late in 1931. Both watches had all silver cases and were used extensively by aviation’s who’s who. They were powered by the robust manual wind pin set caliber 18.69N movement, with the ‘N’ standing for nouveau or new execution.

These first two creations were used by Weems when giving air navigation training to Lindbergh after his New York to Paris crossing. They were likely handed over to Admiral Byrd for his first Antarctica expedition that departed in October 1928.

On February 17th, 1930, a letter from Weems to Lindbergh discussing the developments in aerial navigation noted, “You will remember the equipment for celestial navigation in May 1928. This consisted principally of the following: The original pair of second setting navigation watches”[4]. Other items included a sextant, line of position book, chart board and nautical almanac.

Speaking about the second-setting watch, Rear Admiral Moffett, who was the chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics for the US Navy Department, stated, “A moveable second-hand dial is considered to be a very valuable one, greatly facilitating the process of keeping a clock set to the exact time.”[5] Developed specifically for aviators with the aircraft squadron’s battle fleet, it was officially designated as a “second setting navigation watch”[6]by the U.S Naval Observatory. These watches were later distributed by them to the US Naval air stations and fleet – filling private and government orders for the next fifteen odd years.

Weems’ February 1930 letter noted that, “at this time the Navy is supplying the sea and air forces with the second setting watch…. In addition, The Weems System of Navigation has sold 50 or 60 of several different models, and 72 of a new model are now due for delivery from the Longines company.”[7]

These 72 were part of Wittnauer order 1395, made in 1929, and would be delivered months later on April 10th and May 2nd, 1930.

Radio direction finders using an onboard receiver and pointer could establish an accurate bearing to a ship as early as 1920. The introduction of the Greenwich Time Signal, also known as the famous BBC pips, by Sir Frank Dyson, followed in 1924. The pips were regulated by two mechanical clocks at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich and could be heard across the world’s airwaves.

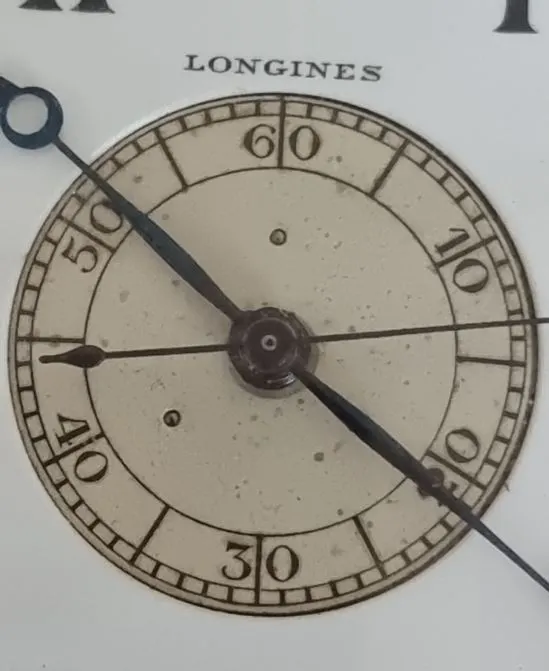

The second-setting watch would play a critical and quintessential role in the advancement of air navigation. The earliest iterations of this watch were edited post factory production, with the sub dial being modified to allow for the exact second to be set, relative to the hour and minute hands.

For the first two second setting watches, Weems noted the modification work as follows, “the second dial was cut out, and a movable dial mounted on a ratchet wheel with sixty teeth was inserted. A small arm, on the left side of the watch, operated by the fingernail moves the dial from one to three seconds per stroke, making it a simple matter to set the exact second. The hours and minutes are set in the usual manner.”[8]

Whilst the two pieces differed mechanically, both had similar modifications that were made by master watchmaker Mr Dadisman of Jessops Jewelers in San Diego.

Longines followed these modifications, with the first prototype of their second setting creation, Weems’ personal watch, arriving on November 30, 1928. They were the first company to produce a specialist, purpose-built second-setting watch. Before 1928, watches were used with sextants for celestial calculations and accurate to, at best, one minute. Their first two unique oversized aviator’s wrist prototypes used repurposed dual time pocket watch movements, originally destined for the Turkish market.

They had an inner chapter ring disc that could be rotated in either direction to gain an additional accuracy of +/- 30 seconds by using a radio signal or other known exact timepiece. Used by Weems, Charles and Anne Lindbergh, Admiral Byrd, Wiley Post and Amy Johnson among others, these timepieces were popular with all of aviation’s who’s who.

Post WWI, air navigation still faced significant challenges. A surplus of leftover pilots, new building materials like aluminum, improved engine size and reliability, brought air navigation’s challenges to the fore. Early pilots depended on dead reckoning, visual navigation and ‘contact flying’ – using roads and landmarks to guide navigation.

Similarly, pilotage referred to navigating by identifiable ground features, ensuring the pilot followed a pre-planned route by matching terrain features on the map with those seen on the ground. Dead reckoning involved setting a compass course based on one’s last known position, speed and bearing while making an allowance for plane drift.

Despite these navigational advances, flying at night remained extremely difficult. A popular saying at the time went “Flying [at night] is no different than flying in the daytime, except you can’t see.”[9] Highlighting these dangers, an aviation manual published by the Chief of Staff of the Army Air Service, Lt. Col. William C. Sherman instructs pilots to be “instructed in cloud flying but warned never to attempt it unless compelled to do so. If overtaken by a mist of clouds, pilots must never let the ground out of their sight. If necessary, they should make a forced landing rather than attempt to get home at night by flying through the mist.”[10]

Barnstorming feats alongside attempts to set new speed, altitude, distance and duration records led to night flights over sea and land in uncharted territories and waters. Air navigation and the determination of one’s position in the air was critical as the boundaries of aviation were pushed further and further. Failure and loss of life was an everyday event. Newspaper headlines captured the highs and lows of this world-shaping period – aviation’s so called ‘Golden years’.

Dramatic improvements in air navigation helped transform commercial transportation and ushered in a military aviation age.

Weems complex adjustable-rate clock technical drawing from 1928 would later serve as the basis for US patent 2008734 that described a ‘method of and apparatus for navigator’s time keeping’. Whilst first filed in July 1929 it was not granted until 1935 prior to the introduction of smaller so called ‘new second-setting watches’. The second setting feature of these models utilized a turning external bezel to make the adjustment against a known accurate time source.

Several thousand of these watches were made by Longines, Movado, Zenith and Omega. Whilst some pieces were supplied for civilian use, the majority were ordered by the military. Post 1935, although the large Longines second-setting watch would sometimes feature ‘Patent USA’ on the dial, Longines was the only one to note the US patent number on the dial for some Wittnauer American deliveries of the smaller cased watches.

Weems was cognizant of the new and ongoing challenges of military aviation. His 1928 article on the adjustable-rate clock noted that, “aviation is developing at a miraculous rate, aerial navigation must make rapid strides to keep pace with the art of flying… The naval service has special responsibilities in the development of aerial navigation and should supply most of the advancement made in the new science”.[11]

One major part of this ‘new science’ of aerial navigation was Weems’ second setting watch, its regulation to sidereal time and subsequent modification into the hour angle wristwatch. It is impossible to overstate the significance of Weems’ navigational work and the concepts behind the creation of the timepiece that carried his name. It is one of history’s most important aviation tool watches.

It allowed for a more accurate and efficient determination of one’s real position in the air and reduced computation errors. In an official US report, the captain of America’s Battle Fleet flagship California noted, “the use of a pair of second setting watches saves 50 percent of the work determining an astronomical fix.”[12] This time saving was essential and critical in the air.

Describing the second-setting concept, the Bureau of Standards sextant patentee, K.H Beiji, stated, “The watch idea is most ingenious, and I kicked myself for not having thought of it before”[13]. The so-called ‘Weems’ model would serve as the backbone of Lindbergh’s improved oversized hour angle model that followed a few short years later that enabled and expedited the calculation of longitude.

The world’s very first second setting pair of tool watches: a modified Patek and Hamilton torpedo boat watch are Missing in Action along with a number of their special relatives. These incredible Flightbird pieces of essential sea and air navigation history remain at large. They help write and colour an incredible chapter on one of air navigation’s greatest tool watches – the Weems second setting watch and the most remarkable group of history making characters who used them.

[1] Possibilities of an Adjustable Rate Clock – US Naval Academy Institute proceedings July 1928

[2] Possibilities of an Adjustable Rate Clock – US Naval Academy Institute proceedings July 1928

[3] Possibilities of an Adjustable Rate Clock – US Naval Academy Institute proceedings July 1928

[4] Letter between Weems & Lindbergh February 17th, 1930. Tennessee State Archives.

[5] Air Navigation, Weems 1931 p401

[6] Air Navigation, Weems 1931 p401

[7] Letter between Weems & Lindbergh February 17th, 1930. Tennessee State Archives.

[8] Possibilities of an Adjustable Rate Clock – US Naval Academy Institute proceedings July 1928

[9] Navigation: From Dead Reckoning to Navstar GPS | Air & Space Forces Magazine

[10] Navigation: From Dead Reckoning to Navstar GPS | Air & Space Forces Magazine

[11] Possibilities of an Adjustable Rate Clock – US Naval Academy Institute proceedings July 1928

[12] Air Navigation – Weems, first edition 1931 p 402

[13] Air Navigation – Weems, first edition 1931 p 402