Lindbergh’s steel 13.33Z would qualify as an uber rare catch for many a collector, especially when it is only through the recent surfacing of 90-year-old correspondence that we now know he actually owned one.

Watches are a prized personal possession; however, any concept of collecting in days gone past was a pipedream. Today, collecting cards, comics, cars, antiques, carpets, watches et al has become a very exact science like behavior and pursuit for some. It should be noted that “the many” think most collectors need to see a shrink.

New watches have their own set of challenges in terms of the advances determining originality given modern machining and technology. Further problems in this space include embellishing; money leads to great original watches acquiring embellished dials like Tiffany & Co, Beyer, Gubelin and Linz.

A quick flick through Ebay will highlight to almost all, that despite a variety of watches being retailed by Tiffany most vintage ads of theirs feature plain Jane normal type dials that were never signed by Tiffany. This is not the subject of my writing.

Vintage watches which have their own life history and there are countless learning experiences for almost everyone that generally involve losing money. Lots can happen in 30, 40, 80 or more plus years.

A learned anonymous Australian Chinese collector and dealer gave me a few choice words of advice twenty plus years ago. At the time, I was inspecting a supposed striped Rolex Prince Brancard ref 971. Unfortunately, this one was originally born as an American market Gruen.

Before I lost my money, he said “all watches tell a story”. A simple but prophetic statement that covered a lot of ground and bases and it has saved me a lot of money over time. The Gruelex Brancard was avoided on that occasion.

There were thousands of registered Swiss watch trademarks by the end of the 1950’s. Many of those did not weather well and their manufacturing records have been lost forever.

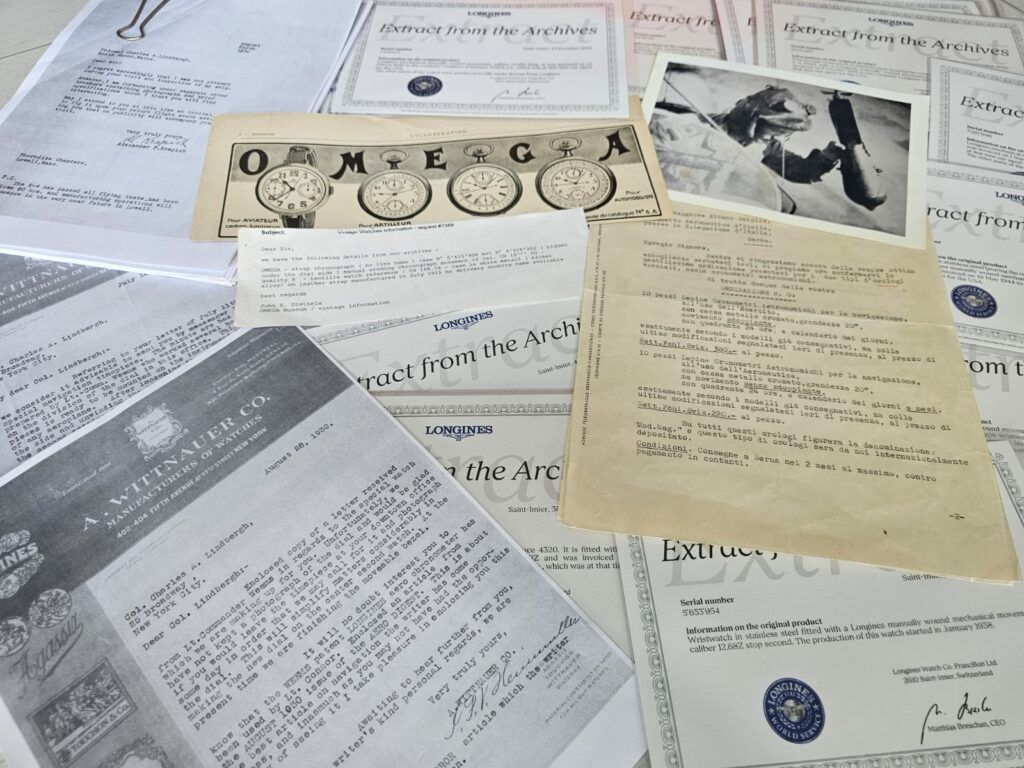

A few of the survivors have wonderful archive information. The list includes Universal, Vacheron, Cartier, Omega, Rolex, Glashute, Breguet, Breitling, Blancpain, Patek, and Longines among others.

Depending on the watch, a manufacturer’s archives will confirm when, to which agent or market it was delivered, and insights into the configuration of the watch when it left the factory.

However, historical events like war, fire, floods, and moving has led to loss or damage of some records. Watches may have changed because of unusual and unforeseen circumstances that may create gaps in the manufacturer’s own register concerning their history.

Depending on the company, sometimes the complete history can be obtained most often with a fee. Some manufacturers details are more complete and include all known information that goes to the heart of the originality of any watch.

One of the most important overlooked issues concerns the role that a manufacturer’s agent may have played over time. Repair work possibly carried out by their own agents in faraway lands that may never have been recorded or lost. Sure, that all sounds a bit like dealer spin, but bear with me.

Almost all manufacturer’s watches have different case and movement numbers. However, there are a few companies like early Breitling Montbrilliant, Glashute, Hanhart chronographs where portions of the movement and case numbers marry up. In their case the three digits on the backcase.

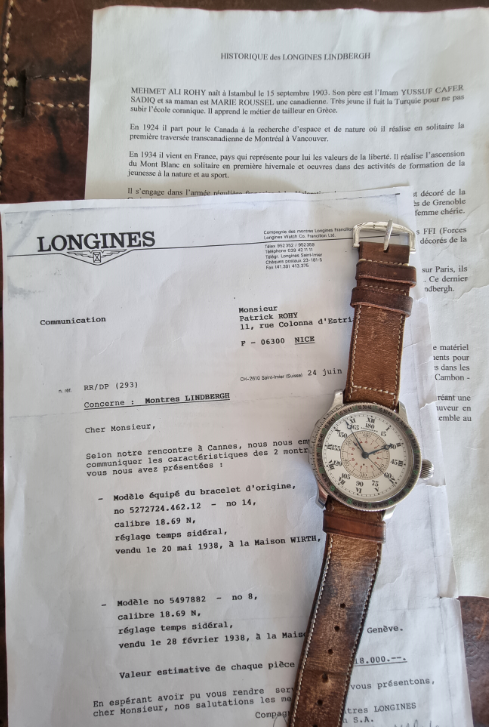

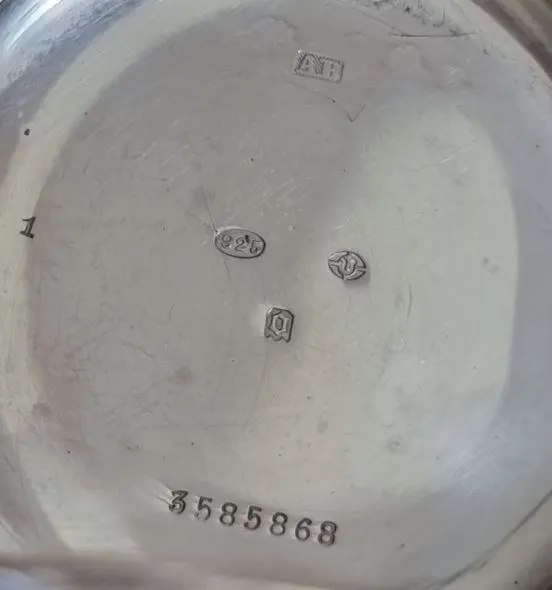

Aside from contract cases, Longines made it easy with a matching case and movement number up until around 1938. Most collectors consider that mismatched numbers generally mean the watch was not born like that and someone may have been tinkering.

Post this time, through until the early 1940’s a dedicated case order number was introduced, replacing the matching case and movement numbering system.

Collectors know that some military watches from all markers can end up a little mismatched during service. Likely because of functionality, expediency, necessity and during reassembly where there are multiple watches involved. They cared little for the concerns of a collector decades later.

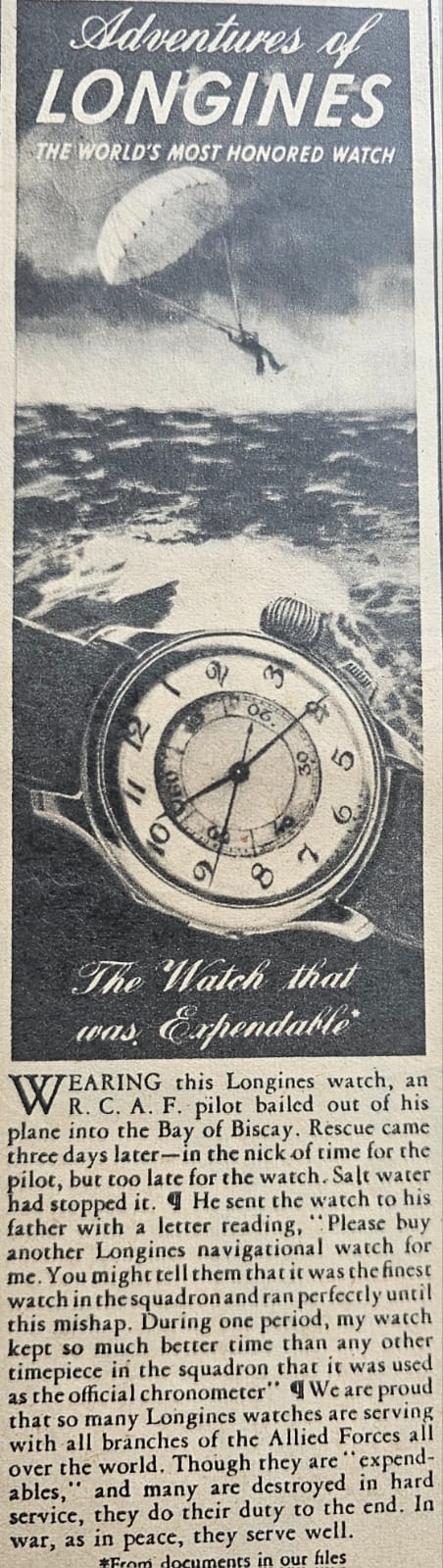

A rare document provides a clear picture into the functioning of Wittnauer, one of America’s largest watch businesses and agents in the 1930’s. Today’s just in time inventory model is anything but normal. Caterpillar the earth moving machinery brand note they can ship 99% of ordered parts to CAT dealers from distribution centres within 24 hours. Air freight companies like Fedex, DHL have only provided expedited global shipping options for fifty plus years.

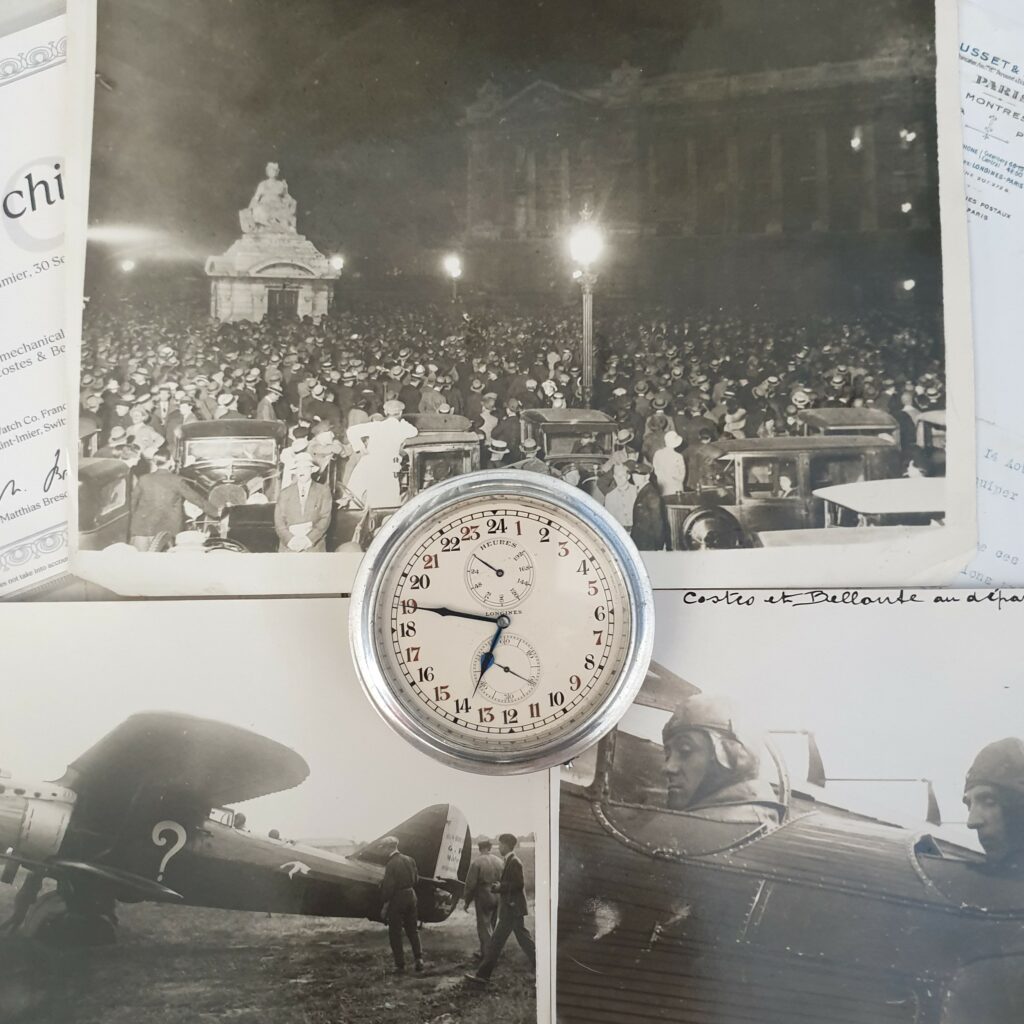

Communication in the 1930’s was by telephone, handwritten mail, telegram services, and whilst air freight existed, it was impractical, limited, slow and extremely expensive. Underscoring the challenges of air travel at this time, the first successful flight of any kind from Paris to New York was only made by Dieudonne Costes and Maurice Bellonte in September 1930.

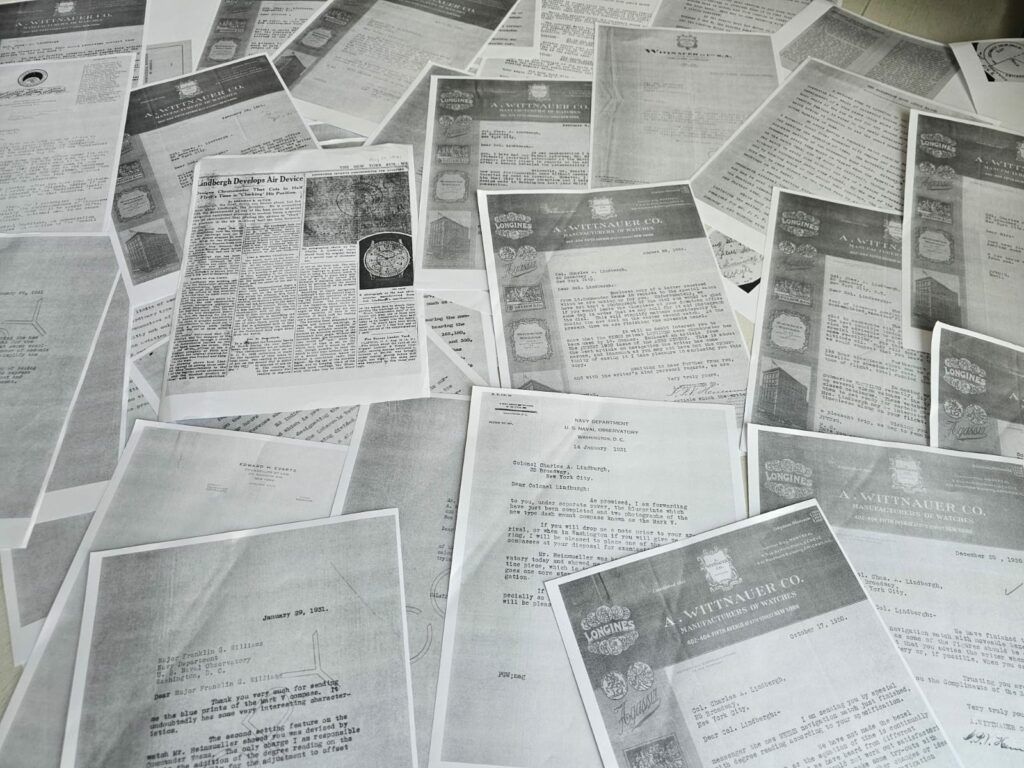

Recent discoveries of detailed correspondence concerning the development of rare and important prototypes, including the Longines Hour-angle, point to an extended drawn out development process. Receiving communication or samples, reviewing, and reverting following testing from different involved parties was a multi-month, and at times year long process due to a range of logistical complexities.

By 1930, Wittnauer was one of the biggest watch sellers in America and had enjoyed enormous success turning their own brand and Longines into household names. However, during the depths of the Great Depression, US sales of the Swiss imports collapsed to their lowest point since 1890, when they were first imported by Albert Wittnauer.

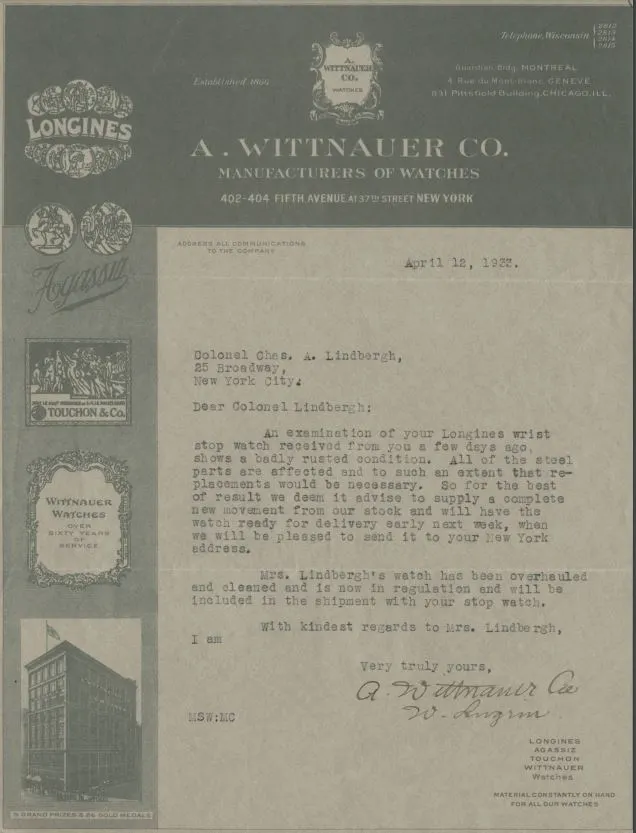

On April 12, 1933, a letter was sent by an A.Wittnauer Co. employee to Colonel Lindbergh goes a long way to highlight their agency relationship with Longines. Given the incredible understanding and value flowing from its contents, it is quoted verbatim.

“An examination of your Longines wrist stop watch received from you a few days ago, shows a badly rusted condition. All of the steel parts are affected and to such an extent that replacements would be necessary. So for the best of result we deem it advise to supply a complete new movement from our stock and will have the watch for delivery early next week, when we will be pleased to bring it to your New York address. Mrs Lindbergh’s watch has been overhauled and cleaned and is now in regulation and will be included in the shipment with your stop watch”.[1]

What can be gleaned from the following communication?

The letter was signed by an employee of A.Wittnauer on the company’s behalf likely indicating staff shortages and even the possible temporary absence of a VP or President during the depths of the Great Depression. We now know the US agent Wittnauer kept complete specialist chronograph movements including the expensive 13.33Z in stock for repairs.

We can surmise that this extended to other popular movement models due to the complexity and time involved organizing an expedient repair. This was likely the case with almost all Longines agents and expedient to having this process organized in Switzerland.

It also highlights an incredible one-week repair service turnaround.

Whilst an agent, Wittnauer was a separate company entity, running a commercial business and completely capable of acting independently.

Whilst they possibly had their own internal records, the movement replacement on Lindbergh’s 13.33Z chronograph watch was something that did not require notification to the St Imier manufacturer.

The catastrophic effects of the depression almost bankrupted Martha Wittnauer and she was forced to sell out, thus ending a 45-year dynasty and family import business. A new Longines-Wittnauer Co. was formed in 1936 and a few short years later this entity generated an incredible 80%[2] of global Longines sales.

Tragically, given multi-decade business changes and the ravages of time and history many of Wittnauer’s records appear to have been lost. Albeit rumors swirl about a secret and incredible cache of these records that may go some way to colouring in the remarkable and unique chapter that Wittnauer and John Heinmuller played in early aviation history.

This exact same issue plays out for almost all watch manufacturer’s agents across the world. The value of these important document discoveries cannot be understated. Fortunately, this Wittnauer letter survived and along with other documents give clues, valuable understanding and insight into the commercial operations of one of America’s biggest watch businesses and agents 90 years ago.

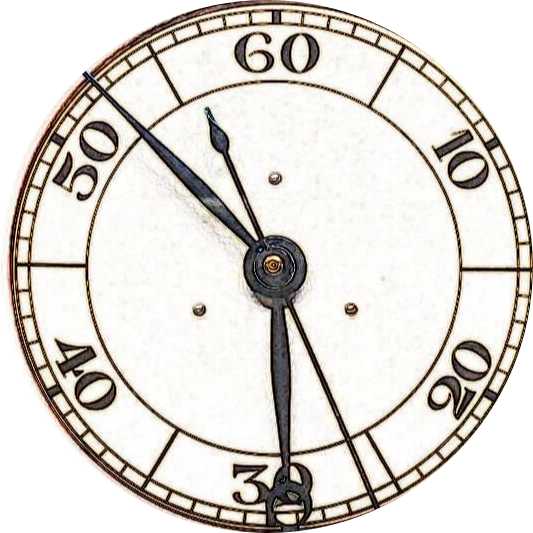

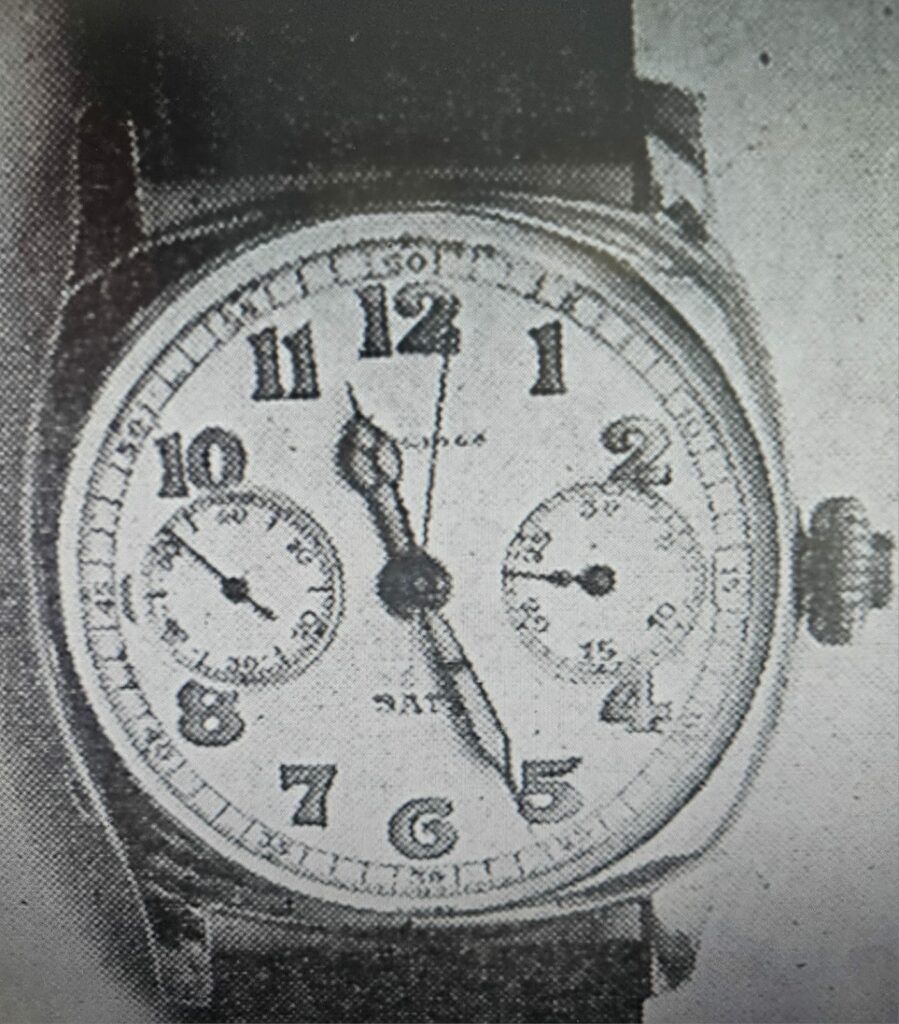

We now know that Lindbergh owned a steel 13.33Z wrist chronograph as the date of the letter precedes the arrival of the 13ZN by years and that the 19.73N pieces were only made with metal, silver or gold cases.

In the case of Longines, most watches pre the introduction of 1940’s dual numbering system should have matching numbers, subject to a few exceptions. This includes the odd anomaly and contract cases supplied to reduce import costs in different markets due to protectionism.

Returning to “all watches tell a story”, we now know that Lindbergh, for a period post his trans-Atlantic crossing was the most “celebrated living person ever to walk this earth”[3]. He also had an original and very rare vintage steel 13.33Z Longines chronograph. This ticking treasure now has mismatched numbers post servicing with Wittnauer to replace the rusty movement in April 1933 and this rare and incredible Longines Flightbird remains at large.

Keep your eyes peeled, it might fly under the radar because we now know what happened in April 1933 with Wittnauer, the American Longines agent. The numbers don’t match, and you now know the reason why! ;). To this day, the current whereabouts of the Lindbergh 13.33Z SATZ signed enamel dial remains a mystery. Where is this special Longines Flightbird hiding today? Another magical watch mystery and hunt continues……

[1] Letter from Albert Wittnauer Co to Charles Lindbergh April 12,1933.

[2] Wittnauer: A History of the Man & His Legacy, Henry B. Friend, Parillo Communications Ltd. P69

[3] Lindbergh A.Scott Berg Macmillan p6