Perhaps more than any other, Lindbergh captured the quintessential American dream within this Golden Age of Aviation. “Lucky Lindy”, a relatively unknown airline pilot, was the antithesis of the stereotypical daredevil persona so associated with aviators.

Post WWI, the commercial and the exploration aviation age had its own set of challenges. Almost no one could see the civil age of aviation that lay a few short years ahead. The nation’s airmen and women left over from the Great War sought to prove aviation’s potential and address aircraft vulnerabilities and expense in international competitions chasing speed, distance, duration, and altitude records. Government funding was tight and prizes were used to advance aviation technology and encourage early aviation pioneers to push the boundaries.

In 1919, a successful French American hotelier Raymond Orteig offered through the Aero Club of America an incredible prize of 25,000USD for a non-stop aviation crossing of the Atlantic, between New York and Paris, in either direction.

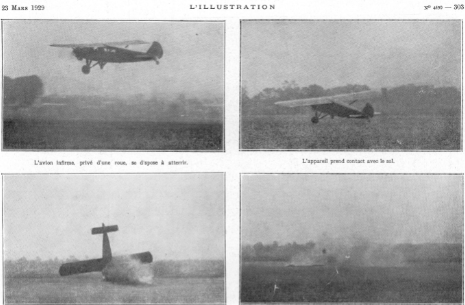

The challenge and prize created a race like environment between a number of known highly skilled pilots and the relatively unknown Lindbergh. French hero René Fonck’s failure in a Sikorsky S-35 in September 1926 ended in catastrophe with two crew losing their lives.

In the summer of 1927, an incredible stage had been set, with Byrd and his three man crew, the duos Chamberlin/Levine, Nungesser/Coli, and Wooster/Davis jockeying to claim aviation’s ‘holy grail’.

Tragically, the two last pairs both perished in their attempts, all four paying with their lives. The least experienced, Charles Augustus Lindbergh would claim the prize in an incredible solo flight shaping the incredible history that followed.

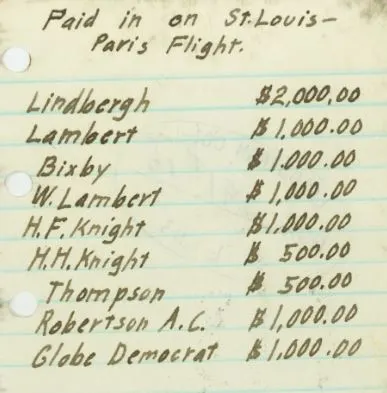

After struggling to find backers, Lindbergh commissioned the near bankrupt and little-known Ryan Aeronautical Company to custom build, with his input, the Spirit of St. Louis N-X-211.

The $10,580 agreed price was made up of Lindbergh’s modest savings including a $1,000 donation from his Air Mail employer and the Spirit of St. Louis Organization.

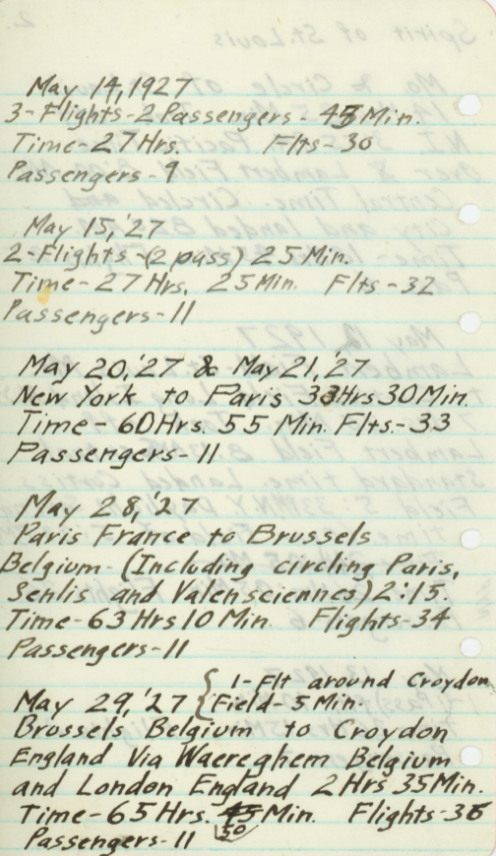

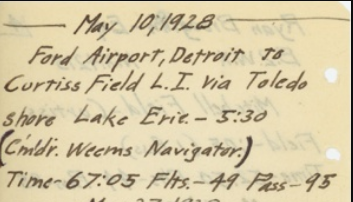

Lindbergh set a new transcontinental time record with an overnight flight from San Diego to New York City, in 20 hours and 21 minutes, whilst testing his new plane. This was just ten days before making global news history crossing the Atlantic.

Despite his lack of experience flying over a large body of water he set out on May 20th, 1927 from Roosevelt Field, determined to break the opinions on what was possible and what was not.

John P.V. Heinmuller recalls in his book that ‘The hearts of all civilization beat faster for Lindbergh during those trying 33 hours and 39 minutes, and there were many who felt that his solo, nonstop attempt was doomed to failure.’[1]

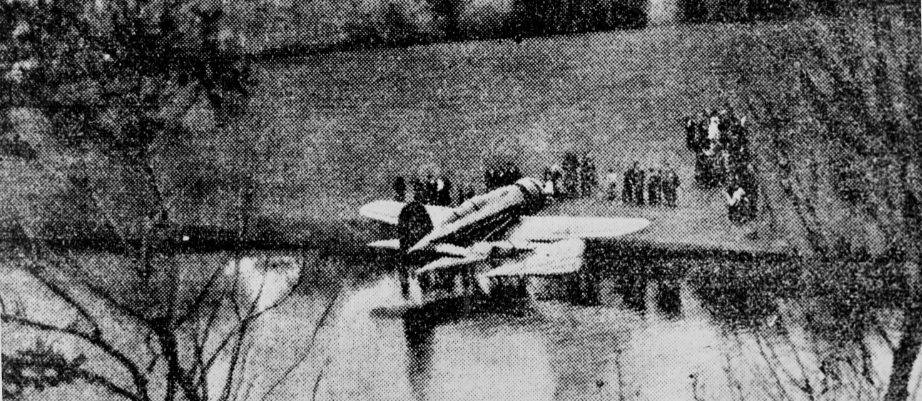

‘He flew a compass course, and arrived at his destination with remarkable exactness, and without using celestial navigation. Of course, he verified his position through dead reckoning, especially after reaching the Irish Coast.’[2] An estimated 150,000 adoring fans were there to greet him after his astonishing solo flight.

Whipped into a hysteria the crowd carried their hero aviator over their heads before Lindbergh was rescued by French military fliers, soldiers and police. Lucky Lindy was thrown headfirst into the spotlight, with people around the world “behaving as though Lindbergh had walked on water, not flown over it.”[3]

After initially struggling to find le Bourget airfield in Paris, he landed at 10.24pm local time to claim the Orteig prize, on May 21 1927, after an incredible solo flight in a wicker chair of 3620 miles.

The one hundred and fifty thousand onlookers formed a human tidal wave and greeted the arrival of the soon to be ‘most famous man in the world’. The first French to greet the plane chanted, ‘Cette fois, Ça va’, this time it’s done!

Lindbergh at just 25, commented, “I was astonished at the effect my successful landing in France had on the nations of the world. To me, it was like a match lighting a bonfire”.[4]

In the days that followed, it soon dawned on Lindbergh that his Atlantic flight crossing “had taken on a significance extending beyond the fields of aviation”.[5] Bleriot who was the first to fly over the English channel said “.. you are the prophet of a new era”[6]

A few short weeks later Chamberlin and Levine’s New York to Berlin flight had Levine claiming to be the very first passenger to cross the Atlantic nonstop. Diamandis and Kotler noted that the Orteig prize ushered in an era of change. “A landscape of daredevils and barnstormers was transformed into one of pilots and passengers. In 18 months, the number of paying U.S. passengers grew thirtyfold. . . . The number of pilots in the United States tripled. The number of airplanes quadrupled.”

John P.V. Heinmuller recalls this Lindy fever in personal letters to his wife published in his book, Man’s Fight to Fly:

The Lone Eagle, during his stay here, is becoming more of an idol every day. He lives in virtual seclusion in the American Embassy, the guest of Ambassador Herrick, who is popular here, a kind fatherly man who has taken the role of advisor to Lindy.

A wave of affection for Lindbergh is sweeping over the country, and apparently over the world. One of the big film magnates tried to reach him to make a film offer, but could not. We hear that he has turned down more than a million dollars in film offers… The people who waited for him at the field seemed to consider him a miracle man, and they were so excited he must have had the impression he was landing among a bunch of wild men in a strange land – if he had any impression at all at the moment.

He has a great deal of bearing, and appears perfectly poised and mild mannered at the big receptions given in his honour.[7]

Lindbergh’s seminal flight, and the attention awarded to him, were instrumental in the development of aviation around the globe. Historian Joe Jackson used the expression “Orteig-inspired madness” to describe the extraordinary progress of aviation in the years that followed the events of May 1927.

Lindbergh was awarded the Medal of Honor in December, 1927, despite the fact that it was reserved for acts of heroism in combat. This distinguished award was offered by President Coolidge at the White House on the 21st of March, 1928. He enjoyed a number of lavish parties and job offers on top of numerous other awards. He was named as Time magazine’s very first “Man of the Year” in 1927 at just 25 years of age. Characteristically mild mannered and somewhat reserved, Lindbergh was overwhelmed by the attention. This seemed to make the public love him ever more.

His name was synonymous with aviation throughout the Western World as every major newspaper, magazine, and radio station in the U.S. jostled to interview him. For the American population Lindbergh had achieved the impossible, inspiring them to reach for the skies both commercially and personally.

Within a year of his Orteig prize, a quarter of the American population, some 30 million, visited Lindbergh and the Spirit of St. Louis.

Throughout 1927, public interest in aviation soared, with applications for pilot’s licenses tripling, licensed aircraft quadrupled and commercial airline passengers grew from 5,782 to 173,405 between 1926 and 1929. Lindbergh’s flight “marked the breakout year of commercial aviation in the United States [and] the beginning of what came to be called the Lindbergh boom.”[8]

The book, WE, detailing the awe-inspiring transatlantic flight, had sold a remarkable 190,000 copies by September 1927. It was translated into a number of different languages and stood firm as a best seller right into 1928. The release of this book coincided perfectly with Lindbergh’s three month tour of the United States. Funded by the Daniel Guggenheim Fund for the Promotion of Aeronautics this tour was to promote and advance aviation.

The Spirit of St. Louis visited 82 cities in all 48 states, with Lindbergh delivering 147 speeches and appearing in countless parades. The 22,350 mile tour saw an American public obsessed with the pilot and everyone wanted to fly.

Distinguished aviator, Elinor Smith Sullivan, later recalls this period: people seemed to think we [aviators] were from outer space or something. But after Charles Lindbergh’s flight, we could do no wrong. It’s hard to describe the impact Lindbergh had on people. Even the first walk on the moon doesn’t come close. The twenties was such an innocent time, and people were still so religious—I think they felt like this man was sent by God to do this. And it changed aviation forever because all of a sudden the Wall Streeters were banging on doors looking for airplanes to invest in. We’d been standing on our heads trying to get them to notice us but after Lindbergh, suddenly everyone wanted to fly, and there weren’t enough planes to carry them.[9]

In just one year Lindbergh’s plane had broken the first major Trans-Atlantic record, flown to all 48 states and 19 foreign countries, logging some 489 hours of flight time.

Lindbergh made a second “Good Will Tour” at the end of 1927 where he met his future wife, and navigator, Anne Morrow. Lindbergh toured 16 Latin American countries from December to February, 1928, covering 9,390 miles. Stops were made in México, Guatemala, British Honduras, Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, the Canal Zone, Colombia, Venezuela, St. Thomas, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Cuba. After this gargantuan trip the Spirit of St. Louis was kindly donated to the Smithsonian Institution, where it remains today.

Lindbergh had used dead reckoning and pilotage to hit France. Incredibly, a post flight weather analysis by John Heinmuller, the man most responsible for recognizing early aviation endeavours noted that an unusual and unique weather pattern existed for the duration of his flight that accounted for a net wind drift of zero. The very first time such a pattern had been recorded and “luck” had found Lindy one more time.

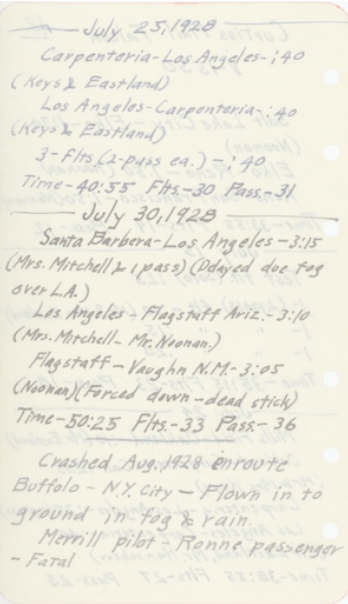

In the year that followed, Lindbergh nearly suffered a tragic outcome after getting lost in ‘The Spirit of St Louis’, on a flight from Cuba to Florida… a haywire compass, stars shrouded in haze, and nothing recognizable from pilotage on the Florida map. Lindbergh’s inexperience and the challenges of air navigation (avigation) led to his 1928 meeting with P.V.H Weems, a young naval officer who was an instructor at the Naval academy in Annapolis.

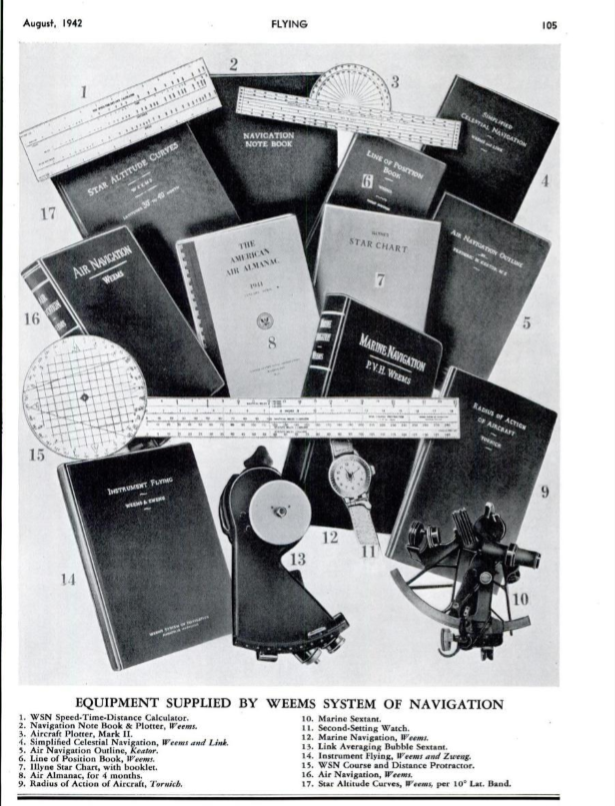

The outcome likely changed avigation forever. Lindbergh’s notoriety and air navigation inexperience was successfully promoted by Weems and he was soon training Lindbergh in his aerial navigation consulting business with the Weems System of Navigation. Lindbergh studied all elements of aerial navigation including celestial, Line of position and star altitude curves. This knowledge was put to work with an improved bubble sextant, the Weems plotter and the all-important second-setting watch.

Improved radio signal accuracy allowed accurate easier time synchronization worldwide, and expanded significantly post February 1924, when the BBC “pips” were developed by British Astronomer Sir Frank Dyson. He used two mechanical Royal Observatory clocks and it was later known as the Greenwich time signal.

The Second-setting watch would form a critical and official part of the Weems System of Navigation, with the very first ‘Weems’ pieces being a handful of modified Waltham Vanguard pocket watches. Lindbergh owned one of these, made the modifications himself and it survives to this day.

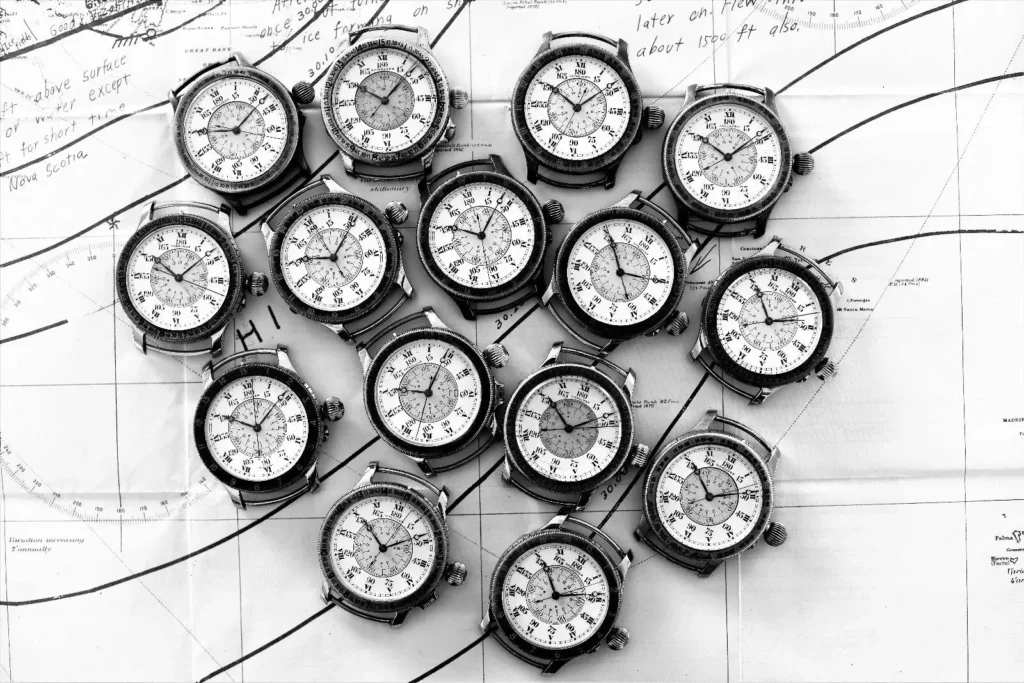

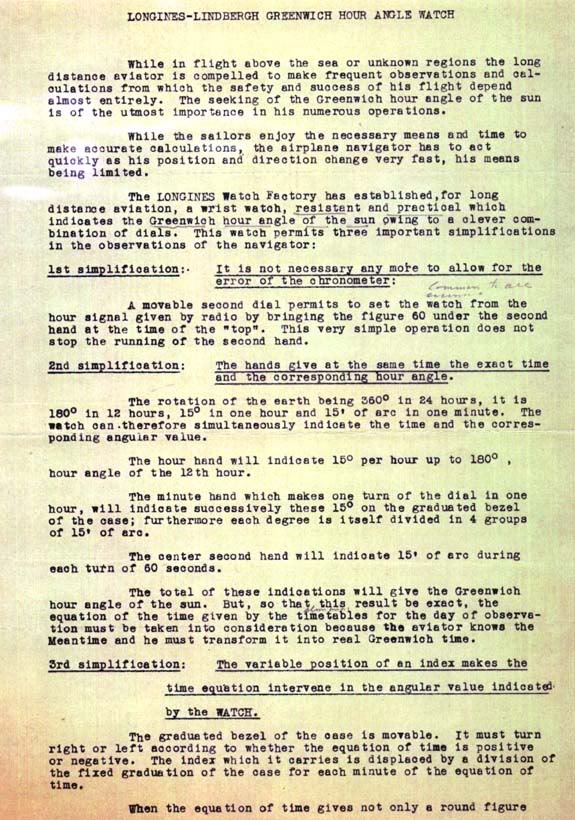

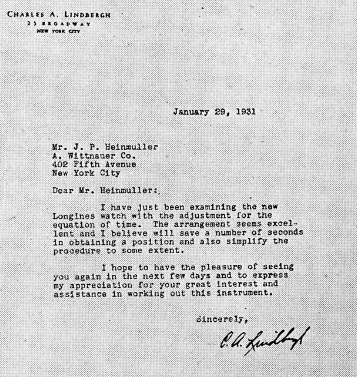

He would soon be a central figure in the testing, evolution and development of the two most important aviator timepieces ever made. The first, the Longines Weems ‘Second-setting’ wristwatch which allowed the exact second to be set, relative to the hour and minute hands. The inner chapter ring disc could be rotated in either direction to gain an additional accuracy of +/- 30 seconds by using a radio signal or other known exact timepiece.

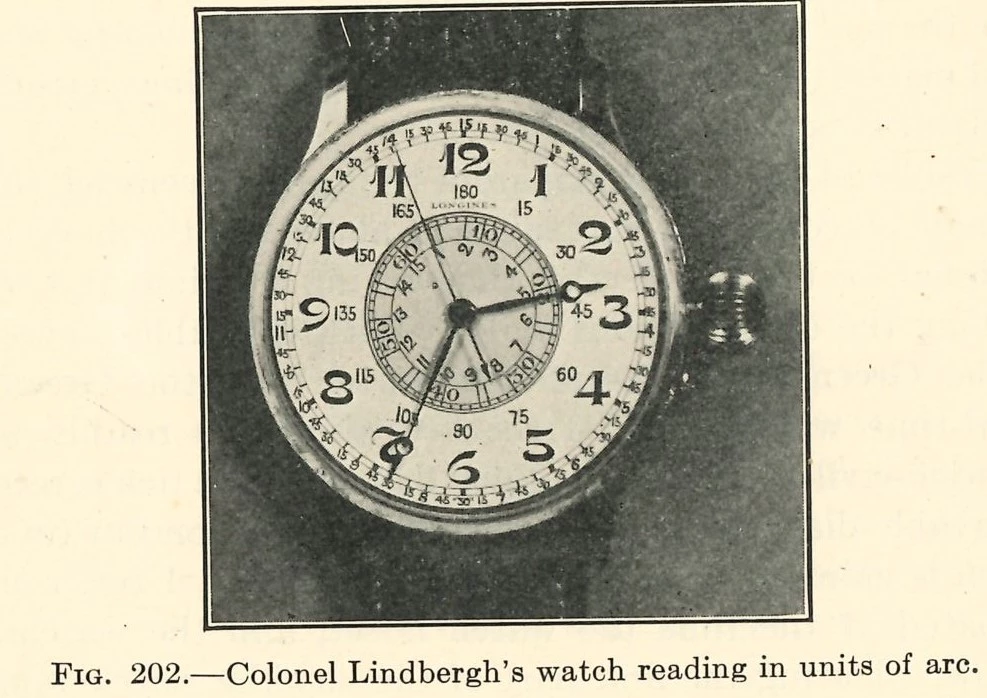

The other, Lindbergh’s ‘Hour-angle’ model which simplified longitudinal calculations by converting time to arc, the 360 units marking the globe.

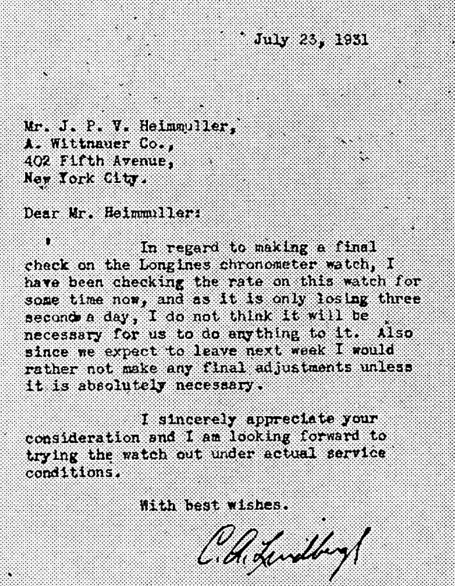

Longines delivered their first version of the Second-setting watch to Wittnauer, 30 November, 1928 for testing and it would be the watch of the creator. Archives records and correspondence point to a special Longines Weems for Lindbergh being delivered to Wittnauer April, 1930.

Early communication indicates a note June 5 from John Heinmuller to Lindbergh saying, “The special watch you designed is now ready. Lt Weems impressed with new design. Make appointment to see sample”. [10]

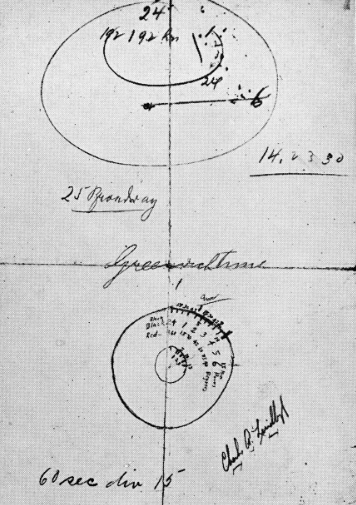

A picture in the Weems Air Navigation book published in 1931 shows a special hand edited hybrid Weems with unit of arc markings on the dial, essentially a ‘Lucy Weems Hour-angle watch’ capable of calculating longitude by converting time to arc. On 20 December, 1930 Longines commented in a letter to Lindbergh that “we have finished the special navigator watch with moveable bezel”.[11]

Lindbergh’s famous drawings and the continued evolution of ‘Lucy’ delivered the very first Hour-angle prototype. The watch acquired a turning calibrated bezel for units of arc with the first prototype carrying the genetic code of the Weems second-setting model.

Lindbergh’s actual Hour-angle is the world’s very first calibrated turning bezel wrist watch and evolved from the Weems Second-setting model.

A recent discovery will soon colour the evolutionary process and rewrite a chapter concerning the development, drawings and history of one of history’s most important and famous watches – the famous Longines Lindbergh Hour-angle.

The ‘Lucy’ Weems Hour-angle and the prototype hybrid Lindbergh were not the only Longines watches of Lindbergh. A special Longines aircraft calotte with serial #43072xx was also marked up with degrees on the dial and delivered to Lindbergh. This piece playing an essential role in the formation and development of the Hour-angle

Lindbergh’s wife, Anne was talented in her own right and she became the very first American woman to receive a glider pilot’s license in 1930. The Lindbergh’s went on to set a new transcontinental speed record between Los Angeles and New York.

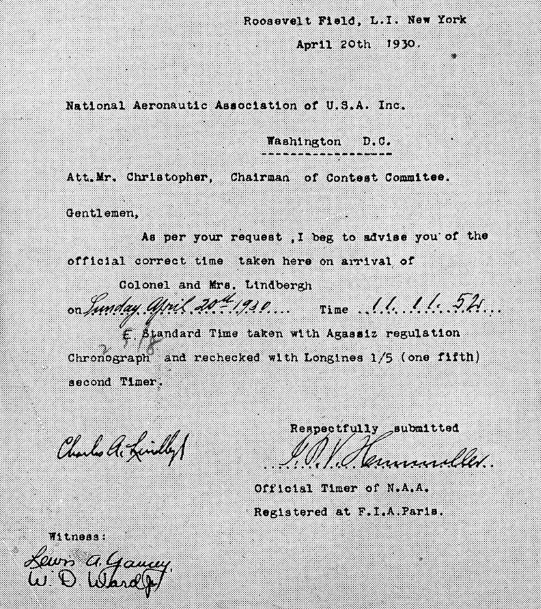

On April 20th, 1930, they arrived in New York after 14 hours and 45 minutes of flight. John P.V. Heinmuller recalls the skill with which this flight was executed:

Both of them navigated in sub-stratosphere by sextant and chronometers, and this time they used a great deal of celestial navigation. Few persons know how deeply Lindy felt the need of improved navigation for safe flying, after he returned from his solo flight to Paris. He at once began a serious study of the subject with Commander P.V.H. Weems, determined to improve his technique, and later Mrs. Lindbergh joined him in the study. Today they use all four known methods: (1) pilotage, (2) dead reckoning, (3) celestial navigation, and (4) radio navigation.

Through these new researches Lindbergh has become one of the foremost aerial navigators of our day, and I am sure flying will benefit immensely as a result, and fliers of future years will owe him much. He has invented a number of his own instruments, and has devised many short cuts for computing the Greenwich Hour Angle.[12]

Both Anne and Lindbergh were keen to develop new routes throughout the skies and set about planning an air route across Alaska and Siberia to China and Japan. In collaboration with Pan American World Airways, they set off in the summer of 1931 with their Lockheed Sirius on a journey that would revolutionize commercial aviation using the Hour-angle prototype just developed. They flew from Long Island to Nome, Alaska and on to Siberia, Japan and China.

A commercial airline route to China, following the Lindbergh’s flight path, was actualised after WWII. Upon reaching China they found themselves in the wake of a natural disaster. The infamous Central China flood had devastated the country. They immediately set to work, volunteering with the relief effort.

Lindbergh was a man of engineering talent with a wide range of interests. Aside from his development of the Hour-angle watch, Lindbergh began to develop the “Model T” pump at the Rockefeller Institute. Designed in conjunction with French surgeon and biologist, Alexis Carrel, this glass perfusion pump was designed to make heart surgery possible.

They designed an artificial heart which proved instrumental in understanding how organs could be kept alive outside of the body. This “Model T” pump was later developed by medical scientists and Lindbergh is credited with making the first heart-lung machine possible.

In 1932, Charles and Anne’s one year old son was kidnapped for ransom. The money was eventually paid in gold certificates with unique serial numbers. These gold certificates would later incriminate the kidnapper who was executed in 1936. After the ransom was paid, authorities went looking for the child in the disclosed located. The child was not there and the remains were found, by chance, six weeks later in roadside woodlands near Mount Rose, New Jersey. A post-mortem confirmed that the child had been murdered before ransom negotiations even began.

The media frenzy that continued throughout this horrifying incident proved overwhelming for the Lindbergh’s. They fled to Europe in secrecy and spent three years living in various European countries, managing and trying to avoid mass media attention as they dealt with the murder of their one-year-old son.

In the 1930’s Lindbergh was actively involved and appointed to senior government committees on aerospace development, securing funding from Guggenheim to support Goddard’s rocket development in Roswell. Before WWII Lindbergh communicated extensively with Germany. At the behest of the U.S. military he was asked to report on German planes, pilots and flying technology.

Lindbergh greatly admired German engineering and was impressed with the developments they had made. He spoke of the strength and skill of the Luftwaffe who had created powerful planes “which combines [the] simplicity of construction with such excellent performance characteristics.”[13] Lindbergh was to inspect all of the German planes to be used in the ever looming war. He developed such a positive relationship with Germany that, in 1938, Adolf Hitler presented him with the Commander Cross of the Order of the German Eagle.

As the atrocities committed by the Nazi party came to light Lindbergh sparked controversy by refusing to give the honour back. Lindbergh, in a rather level headed manner remarked, ‘It seems to me that the returning of decorations, which were given in times of peace and as a gesture of friendship, can have no constructive effect. If I were to return the German medal, it seems to me that it would be an unnecessary insult. Even if war develops between us, I can see no gain in indulging in a spitting contest before that war begins.’[14]

Throughout the Second World War, Lindbergh strongly advised against American involvement. This was a very controversial view with many Americans branding Lindbergh a Nazi sympathizer. In 1940, he became the spokesman for America First, urging America not to enter the war, arguing in favour of upholding the Monroe Doctrine. President Roosevelt publicly shamed his views, picking up on American public outrage and, in 1941, Lindbergh resigned as a colonel from the United States Army Air Forces.

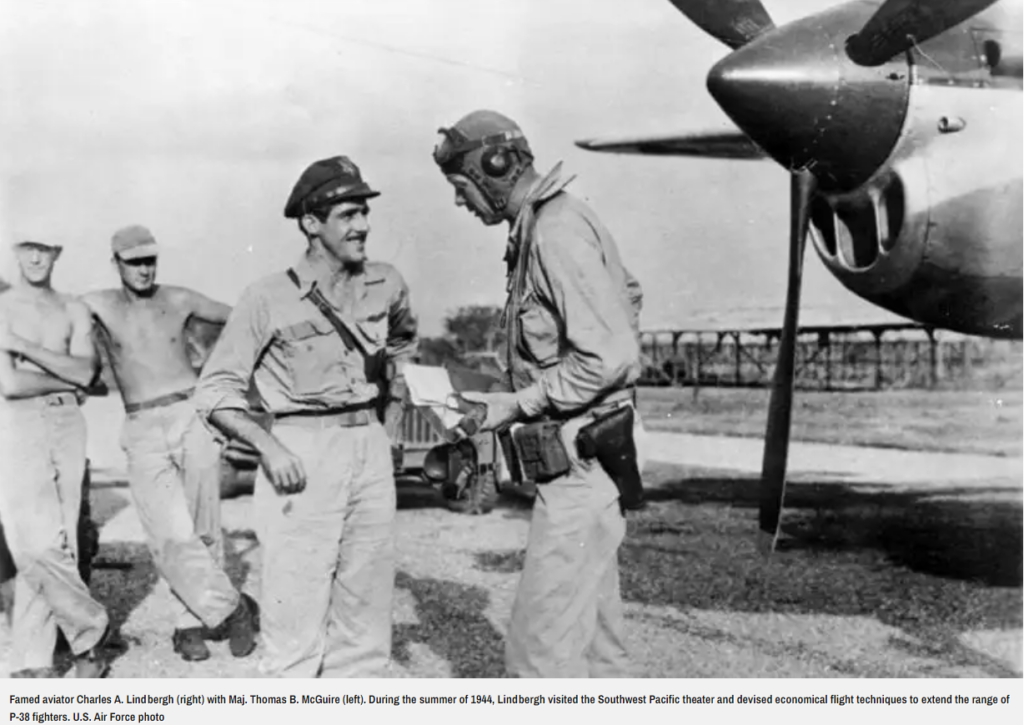

Nevertheless, when America did in fact enter the war, after the bombing of Pearl Harbour, Lindbergh immediately volunteered for active military service. By order of the White House his request was denied. Still desperate to help, Lindbergh entered the battle as a civilian. He worked as a consultant to a number of aviation companies producing bomber planes. He advised Marine pilots on safe take-offs with heavy bomb loads and on May 21st, 1944, Lindbergh piloted his first combat mission.

Lindbergh went on to fly bomber raids on Japanese held positions. As a civilian he went on to fly 50 combat missions throughout 1944. He made innovative changes to both aviation equipment and technology as well as continually advising pilots. Despite being rejected by the armed forces, he did everything he could to help when America entered the war. His reputation amongst the American public was smeared for life and never fully recovered after WWII.

The post-war years were spent advising both the Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force and Pan American World Airways. Within this time he visited Apollo 8 the day before its launch and was present at the launch of Apollo 11. He spent the latter years of his life deeply concerned with the conservation of endangered species.

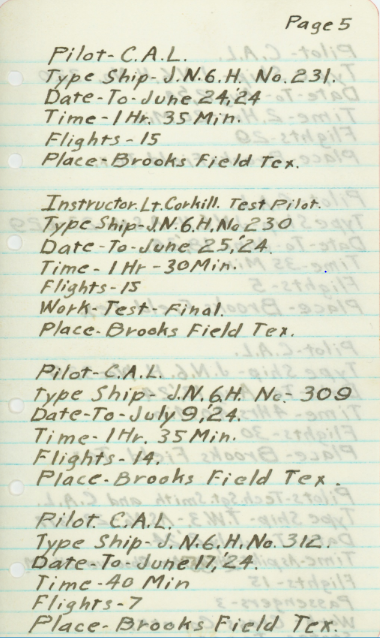

A truly fascinating man and skilled aviator, Charles A. Lindbergh was born on the 4th of February 1902 in Detroit, Michigan, U.S. From a young age, he displayed a keen interest and aptitude for mechanics. He was fascinated by the idea of flight and eventually left his studies in mechanical engineering to enrol at the Nebraska Corporation’s flying college in 1922. He spent much of his early career as the barnstormer, “Daredevil Lindbergh,” quite unlike Lindbergh’s reserved character.

He performed death defying stunts as a wing walker and parachutist throughout much of 1923. He took a break from barnstorming in 1924 at the bequest of the United States Army Air Service in order to complete a year of military flight training. By the end of this year only 18 of an original 104 cadets survived the training, with Lindbergh almost perishing eight days before graduation in a mid-air collision. He bailed out in time and earned his Army pilot’s wings, graduating first in his class in March 1925. Lindbergh later reflects upon his lifelong passion for aviation:

The life of an aviator seemed to me ideal. It involved skill. It brought adventure. It made use of the latest developments of science. Mechanical engineers were fettered to factories and drafting boards while pilots have the freedom of wind with the expanse of sky. There were times in an aeroplane when it seemed I had escaped mortality to look down on earth like a God.[15]

Lindbergh’s dedication to aviation from the days of wooden planes to supersonic jets inspired countless American’s to pursue the skies. This love of flight endured well into the age of space exploration as he bore witness to the launch of Apollo 11. His legacy is far reaching, inspiring flight right into the 21st century.

Having died on August 26th, 1974, at 72 years of age; pioneers are still inspired by Lindbergh to this very day. In 1993, Peter Diamandis reconsidered the merit of competitions with cash prizes in the name of progress and advancement. After reading The Spirit of St. Louis, which detailed Lindbergh’s 1927 Orteig flight, Diamandis happened upon an idea. If Lindbergh’s seminal flight could raise the profile of commercial aviation then why could a space prize not repeat the same trend? Julian Guthrie writes:

From the time he was 8 years old, when he watched Apollo 11 land on the Moon in July 1969, he had dreamed of going to space. But NASA, once the maker of magic, now had a costly and flawed space shuttle program. There was no private space industry, and no way for an average citizen to get out of Earth’s atmosphere. Only a few of the lucky ones who made it into NASA’s astronaut program would ever actually fly to space.[16]

Peter went on to organise a weekend retreat for scientists, investors and engineers to talk about commercial space travel. After all, the idea of commercial flight was as wild a dream to citizens in 1927 as commercial space travel is to us now. He suggested a space prize, not dissimilar to the Orteig Prize and everyone began sketching out ideas for private spaceships, brainstorming on how to go forward.

After this successful meeting, Peter reflected: ‘This is the story of men and machines and the dreams that entwine their lives. It is, perhaps, our oldest fable: the attempt to touch the heavens.’[17] The prize was eventually won on October 4th, 2004 by Mojave Aerospace Ventures. Today, Richard Branson continually works toward a commercial space shuttle and both Lindbergh and Orteig live on.

Bibliography

Berg, A. Scott. Lindbergh, (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1998), as cited in Belfiore (2007)

Guthrie, Julian. ‘How Charles Lindbergh Inspired Private Spaceflight,’ Time, (AOL Time Warner: New York City, Sept. 20, 2016), http://time.com/4461689/how-to-make-a-spaceship/

Heinmuller John P.V. ‘IV Charles Augustus Lindbergh,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945).

Jennings, Peter. & Brewster, Todd. The Century, (New York: Doubleday, 1998).

Lindbergh, Charles. Charles Lindbergh An American Aviator (linbergh.com), http://www.charleslindbergh.com/history/index.asp

Ross, Stewart Halsey. How Roosevelt Failed America in World War II, (McFarland & Company, Inc.: Jefferson, North Carolina and London, 2006).

[1] John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘IV Charles Augustus Lindbergh,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. 68.

[2] John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘IV Charles Augustus Lindbergh,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. 72.

[3] A. Scott Berg, Lindbergh, (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1998), as cited in Belfiore (2007), pp. 17.

[4] A. Scott Berg, Lindbergh, (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1998) p135

[5] A. Scott Berg, Lindbergh, (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1998) p138

[6] A. Scott Berg, Lindbergh, (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1998) p143

[7] John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘IV Charles Augustus Lindbergh,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. 73.

[8] A. Scott Berg, Lindbergh, (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1998), as cited in Belfiore (2007), pp. 17.

[9] Peter Jennings and Todd Brewster, The Century, (New York: Doubleday, 1998), pp. 420.

[10] Longines through Time The story of the Watch Stephanie Lachat p116

[11] Longines through Time The story of the Watch Stephanie Lachat p116

[12] John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘IV Charles Augustus Lindbergh,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. 75.

[13] Stewart Halsey Ross, How Roosevelt Failed America in World War II, (McFarland & Company, Inc.: Jefferson, North Carolina and London, 2006), pp. 44.

[14] Stewart Halsey Ross, How Roosevelt Failed America in World War II, (McFarland & Company, Inc.: Jefferson, North Carolina and London, 2006), pp. 44.

[15] Charles Lindbergh, Charles Lindbergh An American Aviator (linbergh.com), http://www.charleslindbergh.com/history/index.asp (date accessed: 21/09/16).

[16] Julian Guthrie, ‘How Charles Lindbergh Inspired Private Spaceflight,’ Time, (AOL Time Warner: New York City, Sept. 20, 2016), http://time.com/4461689/how-to-make-a-spaceship/ (date accessed: 20/09/16).

[17] Julian Guthrie, ‘How Charles Lindbergh Inspired Private Spaceflight,’ Time, (AOL Time Warner: New York City, Sept. 20, 2016), http://time.com/4461689/how-to-make-a-spaceship/ (date accessed: 20/09/16).