A member of the Longines Honor Roll, John Polando, was an experienced mechanic and aspiring pilot. Having learned how to fly in 1927 a fortuitous meeting with Russell Boardman at a ‘Wall of Death’ motorcycle event led Polando toward realizing his air-borne dream.

Boardman was employed as a rider and they stuck up a friendship that eventually led to a record breaking long distance flight to Istanbul. These flights were crucial in the early advent of aviation as they enabled a greater understanding of the difficulties and intricacies of aerial navigation.

The discoveries made in awe inspiring flights such as Polando’s have informed future flights to come, records later broken and the emergence of safe and reliable commercial aviation.

Born in Massachusetts on September 6th, 1901, Polando would go on to live an exciting air borne existence.

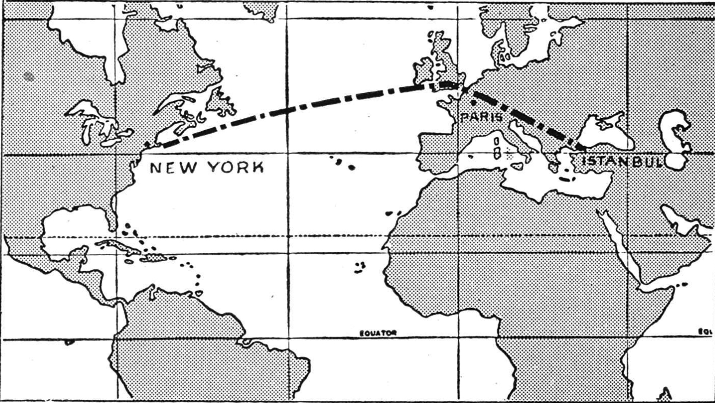

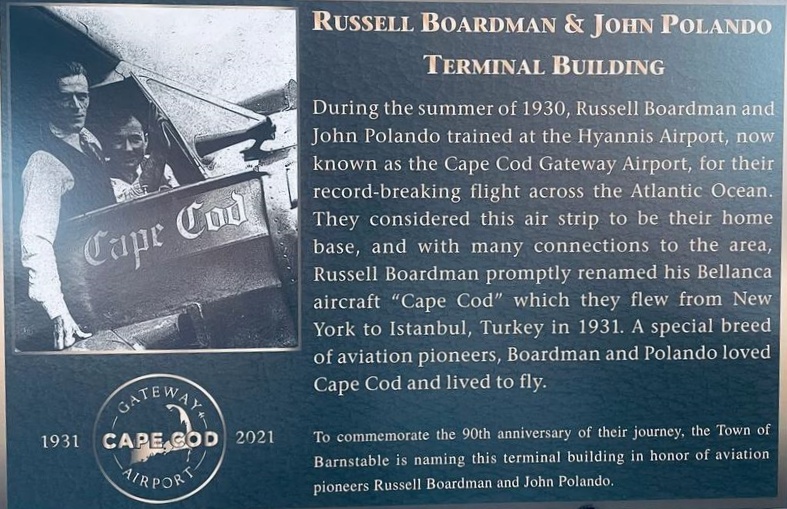

His first notable achievement in the air, is that of his seminal 1931 long distance flight from New York to Istanbul. Boardman and Polando aimed to fly non-stop in order to prove the feasibility of such a journey.

Unique in nature, their visit to Turkey was novel in every way. There was no military objective, no push to sell Turkey any aircraft, just the desire to see a new country and to push the known limits a little further.

This flight was made to promote civil aviation, which did not exist at the time in Turkey. There were only two airlines operating in Turkey, the Italian Aero Espresso, which flew seaplanes from Brindisi to Büyükdere, as well as CIDNA, which was the predecessor to Air France.[1]

They planned for nearly two years pouring over maps and charts, ensuring that they were as prepared as possible for this gargantuan undertaking. They enlisted the Bellanca plane, Cape Cod, for the epic non-stop journey.

The Distance Flight

They loaded the Bellanca plane with 50 hours’ worth of fuel and prayed she’d lift herself into the air. A faltering start, Cape Cod, failed to take off twice; struggling along Floyd Bennet Field on July 28th, 1931.

The third attempt proved successful. After narrowly avoiding disaster Polando and Boardman were airborne.

The flight was not without difficulty as an onslaught of thick fog provided little visibility to aid the pilots. They were forced to alter the course, changing altitude in order to escape the fog and darting in between the Alps while flying blind.

They suffered through dense fog across the entire Atlantic passage. Zero visibility made observations impossible and the two pilots relied heavily on their instruments and navigation knowledge.

Polando made it through the fog and onto Paris, as luckily, their ‘artificial horizon, the directional gyro and other instruments and navigational equipment were working perfectly.’[2]

At Paris, on Le Bourget airfield, they dropped a bag of mail attached to a parachute. This included the latest edition of the New York Times.

They spent 6 hours dodging the Alps, failing to distinguish between clouds and mountains in weather that offered no clear visibility. Boardman later wrote ‘We longed for daylight,’[3] as they zig-zagged through valleys and mountain peaks, unsure of their fate.

They almost abandoned the flight through the Szretinye Mountains as, once again, visibility proved impossible.

The clouds slowly lifted and as they resumed their original course, crossing the Balkan Mountains, they were elated to discover the emergence of the Black Sea of Marmora framing the ornate minarets of Istanbul.

Boardman and Polando had reached their destination after no small amount of difficulty and uncertainty.

Istanbul

They were greeted with great fanfare upon reaching Istanbul. Massive crowds had gathered to cheer their arrival with members of the Turkish Government and a representative from the United States. They were warmly welcomed by the Turkish people:

their ten-day stay in Turkey was beyond all their expectations. There were banquets, visits to the city’s historical sites, sporting events in their honor, gifts of carpets, Turkish Medal of Honor ribbons, silver medallions from the Governor’s office, Turkish cigarettes, even custom-made suits and shoes, which the two wore proudly throughout their stay, and even a great, big ‘evil-eye’ which three Turkish girls hung from the tail of the Cape Cod on their departure from Turkey.[4]

Between July 28 and 30, 1931 they had flown a total of 5,011 miles, non-stop, in 49 hours and 8 minutes. This record would stand firm for two years.

Boardman died in a tragic crash not long after their record-breaking flight but Polando went on to fly for the rest of his life.

He worked as a test pilot for the East Coast Aircraft Corporation of Boston, from 1929 to 1931. He served with the Twenty-Sixth Division as part of the Massachusetts National Guard for several years.

After his groundbreaking Istanbul flight he was promoted to First Lieutenant.

The MacRoberston Race

In 1934 Polando took part in the 11,123-mile MacRoberston Race from England to Australia. Polando and co-pilot, John Wright, were forced down in Mohammerah in the Persian desert, and immediately arrested.

Held captive for no justifiable reason, their freedom was obtained by British residents. They had been detained so long that they were hopelessly behind. The pilots decided to abandon the MacRobertson Race in light of these circumstances.

World War II

During WWII Polando served as a pilot with the 445th Bombardment Group. He was forced down after being hit with flak over Odertal, Germany.

The danger of falling bombs meant Polando could not re-join the formation, who were flying above him, heavily loaded with ammunition. Polando could not gain enough altitude to fly beside the group and instead made an emergency landing in Soviet-occupied Poland.

He spent two weeks with the Russians before being flown to a base in Poltava and retrieved by his men.

The overwhelming reception from Turkey after his Istanbul adventure really stuck with Polando.

It is said that ‘When John was a captain flying bombers in the US Air Force during World War II, he proudly pinned on the broche presented to him by President Ismet Inönü, when his country entered the conflict during the final few weeks.’[5]

Perhaps the memento offered him luck as he emerged from the war relatively unscathed.

Polando lived until the age of 83, dying from injuries sustained in an aircraft accident. His accomplishments are recognized by Barnstable Municipal Airport by adding Boardman-Polando Field to its name.

Footnotes

- STUART KLINE, ‘JOHN POLANDO 1901-1985,’ Early Aviators, (earlyaviators.com, 5/17/01), http://www.earlyaviators.com/epolando.htm (date accessed: 29/08/16).

- John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘X Russell Norton Boardman and John Lewis Polando,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. 153.

- John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘X Russell Norton Boardman and John Lewis Polando,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. 153.

- STUART KLINE, ‘JOHN POLANDO 1901-1985,’ Early Aviators, (earlyaviators.com, 5/17/01), http://www.earlyaviators.com/epolando.htm (date accessed: 29/08/16).

- STUART KLINE, ‘JOHN POLANDO 1901-1985,’ Early Aviators, (earlyaviators.com, 5/17/01), http://www.earlyaviators.com/epolando.htm (date accessed: 29/08/16).

Bibliography

Heinmuller, John P.V. ‘X Russell Norton Boardman and John Lewis Polando,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945),

KLINE, STUART. ‘JOHN POLANDO 1901-1985,’ Early Aviators, (earlyaviators.com, 5/17/01), http://www.earlyaviators.com/epolando.htm