John P.V. Heinmuller, who acquired the title “Aero One” would go on to become the U.S. director of the Longines-Wittnauer Co entity in 1936 and bore witness to the most exceptional flights in aviation history. It is almost serendipitous that Heinmuller should come to prominence at the moment in which aviation took front and center stage.

Love of Aviation

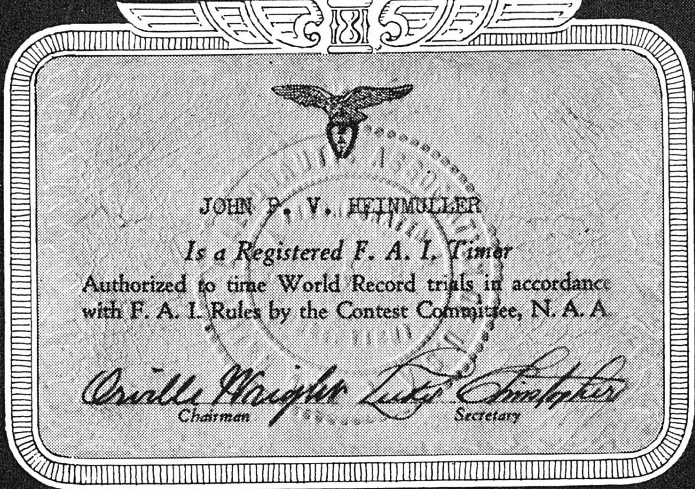

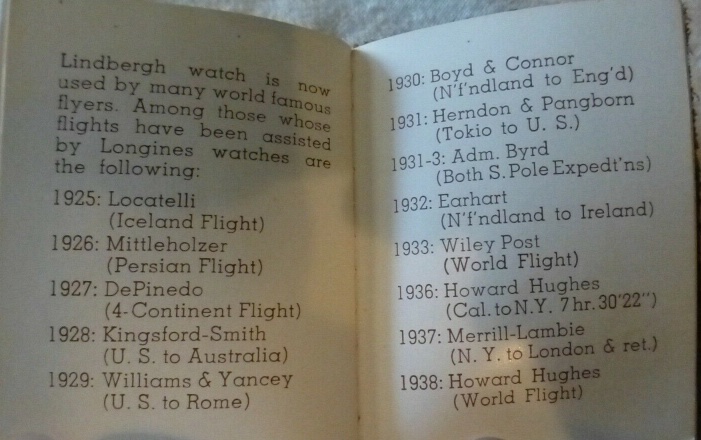

Heinmuller first served as the chief timer for the Aeronautic Association during Lindbergh’s historical 1927 solo transatlantic flight.

This flight captured public imagination inspiring a generation to take to the skies. Lindbergh raised both the profile and financial viability of flight upon landing at Le Bourget field after 33 and a half hours. Heinmuller remembers this flight in his acclaimed aviation book, Man’s Fight to Fly,

“At exactly 10:21 I clocked the appearance of a white plane that circled over the airfield twice. Then to the amazement of the shouting and awed spectators the big Spirit of St. Louis swooped down to a graceful and perfect landing right in front of the Administration building. It was just 10:22P.M. Now the crowd ran wild and broke through the safety lines again. People swarmed around the Lindbergh plane and tried to snatch parts of the wings for souvenirs. Reserve guards had been called; they fought pathways to the plane, surrounded it and rescued the tiered flier”.[1]

Having been a lifelong aviation enthusiast Heinmuller describes, in detail, this awe-inspiring experience. As a skilled watchmaker, pilot and official timer, Heinmuller went on to record a vast array of exceptional and seminal flights.

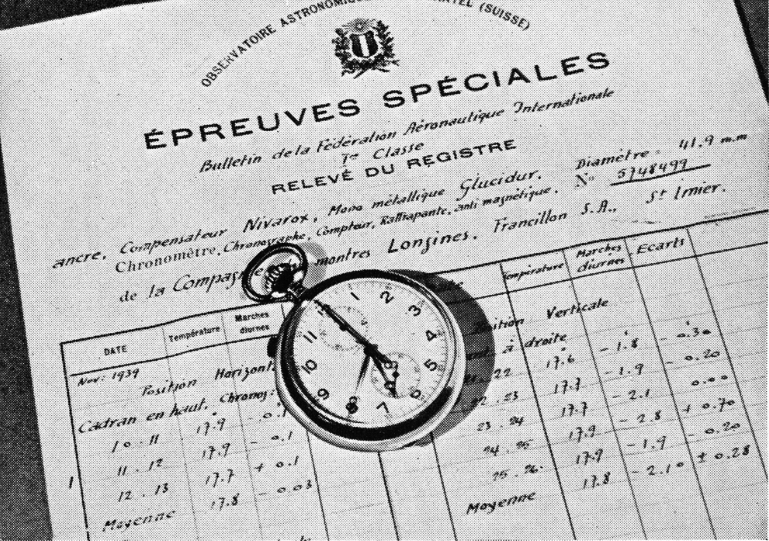

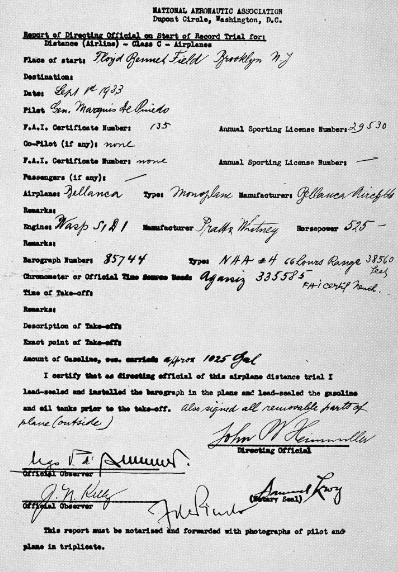

Serving for 30 years as the chief timer of the National Aeronautic Association and the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale, Heinmuller’s most notable achievement was the organization of ‘the Timing Contest Board of the National Aeronautic Association in accordance with the chronometric specifications of the Federation Aeronautique Internationale.’[2] He also served the president of the American Air Mail society, an avid aerophilatelist to the bones.

His love of aviation began at a young age with airport memorabilia. In 1909, at just 17, the obsession began with a zeppelin souvenir sent by a friend. Heinmuller went on to collect of 5,000 Zeppelin articles. ‘Some were acquired by purchase or exchange with other collectors; others were acquired by writing Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin directly, asking him to send a postal souvenir from an advertised flight. Part of his acquisitions derived from the well-known Thompson, Steiner, and Luderman collections.’[3]

His flair for precision and organization emerged as he began compiling lists of all the dates and routes of every zeppelin flight. His avid interest caught the attention of Von Zeppelin and zeppelin commanders Dr. Hugo Eckener and Ernst Lehman. He became friendly with the very aviators he so worshiped and was present at the majority of zeppelin landings.

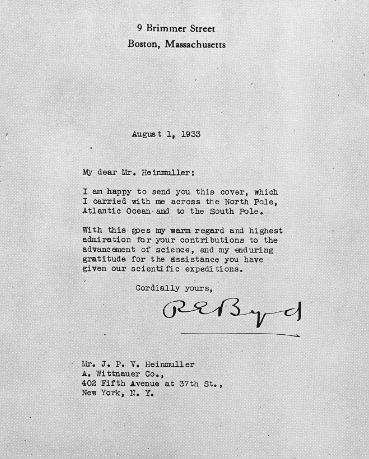

He went on to work closely with Admiral E. Byrd, the infamous polar explorer, amassing an airmail collection of each of Byrd’s notable flights.

Heinmuller generously donated 2,000 of his 5,000 zeppelin covers to the National Postal Museum in the 1950s.

Heinmuller exuded a real love of aviation; a love which lasted throughout his distinguished career. He bore witness to some of histories finest tales of daring and adventure.

Recording the Records

In 1912, at age 20, he departed St Imier for Wittnauer, the American agent for Longines. During World War I, Heinmuller was instrumental in the development of anemometers, timing instruments and temperature gauges. He participated in innumerable test flights where these technologies were put through their paces in the air.

Already familiar with the intricacies of watch construction, Heinmuller ‘developed a complete line of navigation timing equipment, including aviation dash-board clocks, turn and bank indicators, altimeters, speed indicators, and compasses in cooperation with outstanding scientists of the day.’[4]

These instruments were used extensively throughout the War effort. This was the beginning of Heinmuller’s work in the development of timing devices and other such intricate instruments.

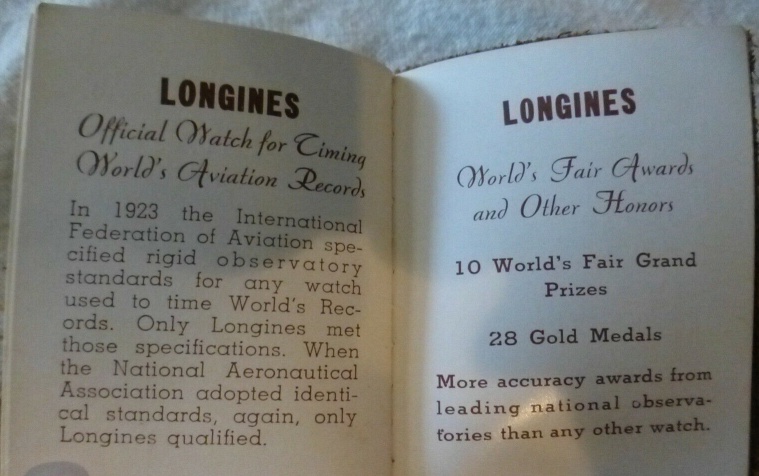

Heinmuller took up employment with Longines-Wittnauer, the US agent in America for Longines. At this time, the latter was renowned as one of the most respected, exacting and trustworthy watch producers of technical instruments and accurate timepieces in the world. Heinmuller was respected by the finest of aviation’s elite during this time. He was revered for his skill, precision, commitment and knowledge of aviation instruments.

These watches were to be used extensively by pioneers like Amelia Earhart, Richard E. Byrd, Howard Hughes, Clyde Edward Pangborn, Wiley Post, Harold Gatty and countless others.

He penned a complete chronology of aviation that remains, to this day, one of the finest journals of aviation’s Golden Age. It is able to relay facts and timings alongside a colorful narrative that builds a vivid picture of this phenomenal time.

It provides pictures of mementos and events alongside personal letters documenting his own experiences of various landings. The back pages trace the history of man’s long held desire to fly; culminating in the actualization of this fantastic dream.

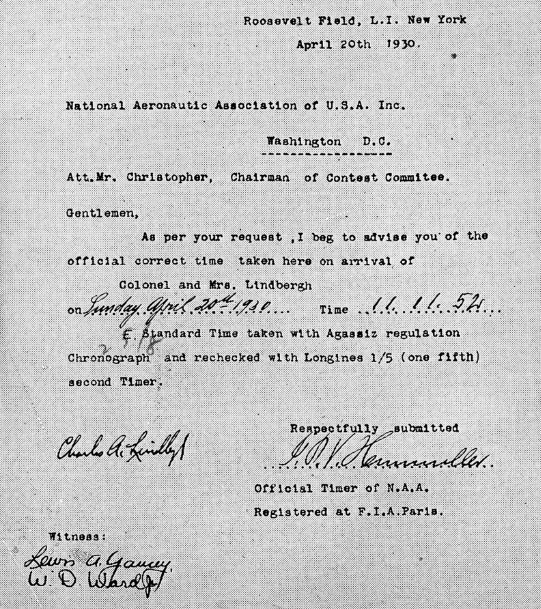

After Lindbergh’s 1927 flight Heinmuller went on to officially record the time of his Los Angeles to New York flight. Not only does he record the time but the finer details of his meeting with Lindbergh alongside his expert observations. In a letter to his wife, he writes:

I have found some extremely interesting and valuable material on the flight Lindbergh and Mrs. Lindbergh made from California to Roosevelt field this year.

Both of them navigated in sub-stratosphere by sextant and chronometers, and this time they used a great deal of celestial navigation. Few persons know how deeply Lindy felt the need of improved navigation for safe flying, after he returned from his solo flight to Paris. He at once began a serious study of the subject with Commander P.V.H. Weems, determined to improve his technique, and later Mrs. Lindbergh joined him in the study.[5]

He goes on to detail Lindbergh’s various inventions and ‘short cuts for computing the Greenwich Hour Angle,’[6] expressing gratitude in being able to work with Lindbergh on these latest innovations.

As a friend and confidant of the famed aviator, Heinmuller was offered an autographed copy of Lindbergh’s book WE. On the flyleaf Heinmuller writes ‘“… and he took a chance and rode the winds, and the gods of all winds smiled on youth – took him across and made of Charles A. Lindbergh the first airman hero of this country.”’[7]

Chronicling the Polar wastes

In 1928 Heinmuller was recruited by Richard E. Byrd for consultation on his upcoming polar sojourn. Together they worked out the issues surrounding timing and navigation in the icy southern deserts.

He recalls: The timing and navigation equipment was thoroughly planned, and it undoubtedly surpassed anything attempted before on a polar expedition. In addition to the normal size instruments, they took along miniature replicas of timing and navigation pieces for use in taking observations during dog sled trips.

There were specially designed small-size chronometers to supplant the cumbersome marine chronometers which traditionally were cherished as irreplaceable until, at the end of World War I, the small, watch sized chronometer was developed.[8]

Heinmuller offered both expert consultation and furnished him with the best equipment and timers for this groundbreaking Antarctic expedition. The trip, including Byrd’s flight over the South Pole, is documented by Heinmuller who is astonished by the discoveries made. He shows a real understanding of their significance in the realms of scientific advancement.

Navigation is particularly difficult at the Pole. Instruments are useless where ‘the longitudinal meridians of the earth converge to what must have seemed a pinpoint to Byrd and his men. Only the exactitude of time calculations enabled him to find his way back, five hundred miles each time, to the base at Little America.’[9]

Heinmuller goes on to map the importance of Byrd’s work and discoveries with an in-depth understanding of Polar navigational techniques. With Heinmuller’s consultation, Byrd was able to traverse ‘the white polar ends of the earth […as] one of the outstanding fliers and explorers of our time.’[10]

The Early Record Holders

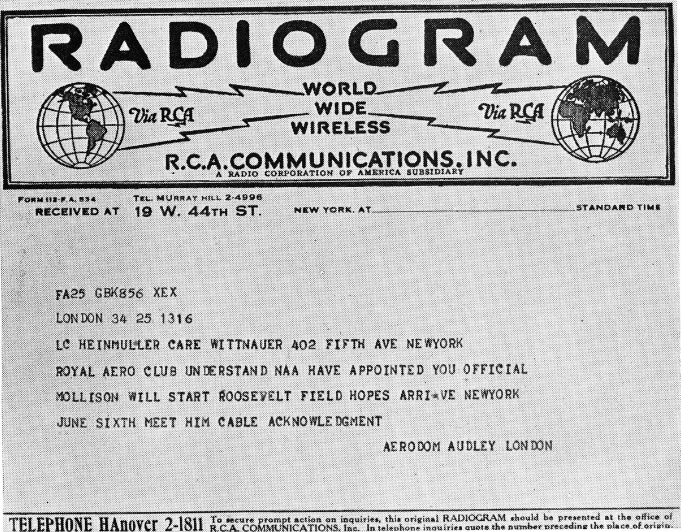

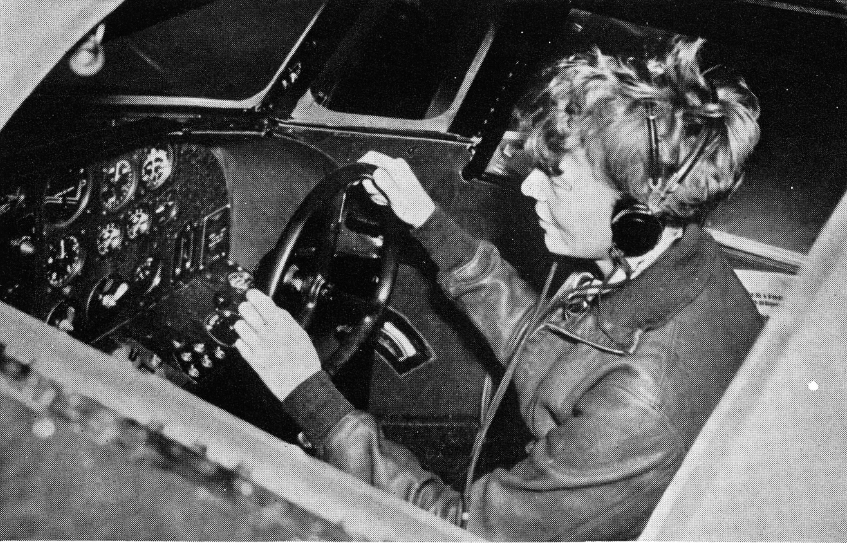

He expresses great adoration toward Amelia Earhart whom he respected as a skilled aviator. Heinmuller traces her early life before detailing her awe-inspiring flights that defied odds and convention. Heinmuller was instrumental in securing Earhart’s official records. After her incredible solo Atlantic crossing of 1932 it took a full year of investigation; gathering witnesses and calculating time discrepancies to satisfy the Federation Aeronautique Internationale.

Heinmuller recalls that ‘During 1932, I had considerable trouble in filling out all the documents for the various records she claimed, and it took until 1933 to fully satisfy the Contest Committee of the FAI. Only after I went to Paris and conferred with Monsieur Tissander, secretary of the association, were the records of Miss Earhart cleared.’[11]

Witnesses had to be gathered to corroborate Earhart’s claims and there was some confusion surrounding the time differences between Newark and Europe. Without Heinmuller’s exhaustive efforts Earhart’s flights may have been for naught.

His devotion to record keeping and his respect for the aviator enabled Earhart to be fully recognized by both the FAI and the various history books not yet penned.

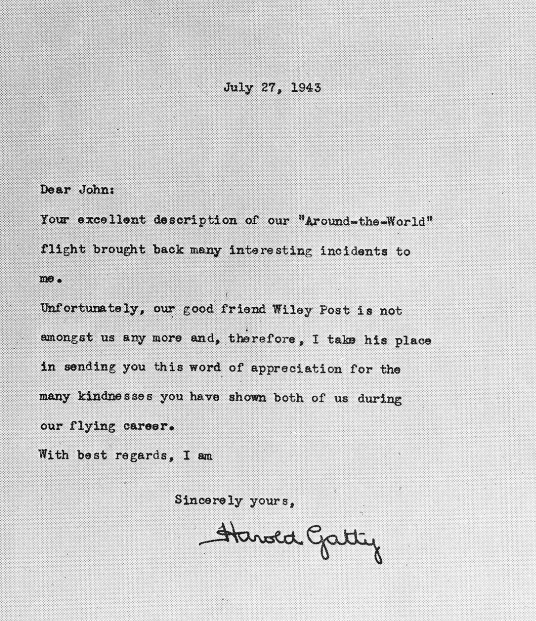

Heinmuller came to personally know both Harold Gatty and Wiley Post well. These famed aviators peaked national interest in 1931 with their incredible round-the-world flight. Gatty was renowned as one of the foremost navigators of his time, dubbed by Lindy as the ‘Prince of Navigators.’[12]

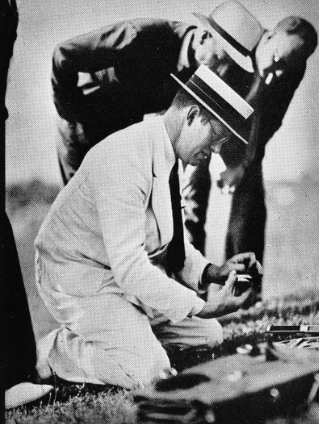

Heinmuller advised Gatty prior to their 1931 flight, aiding in the development of Gatty’s newest drift indicator invention. The device ‘was made mostly out of gears and other clock and watch parts, and which worked so successfully that later the Army and Navy adopted it.’[13]

This flight proved instrumental in the development of aerial navigation. Alongside P.V.H Weems, Gatty, Post and Heinmuller spent many an evening pouring over their maps and flight log, studying every detail of their successful circumnavigation of the globe. They came to the conclusion that ‘many lessons of navigation had been learned through this outstanding flight, and we felt it would take years to better the time of 8 days, 15 hours and 51 minutes. But Wiley Post himself changed our minds.’[14]

Following his flight with Gatty, Post went on to circumnavigate the globe, on his own, in 7 days, 18 hours and 49 minutes. Heinmuller details the advantage of the new Sperry robot installed on his plane. This would allow Post to take a few short naps as the autopilot device guided the aircraft.

Post was the first flier to use the instrument on a long-distance flight. Heinmuller himself was with Carlson, ‘the engineer from Sperry’s, who worked all night before the departure to properly install and test the instrument.’[15] He goes on to map the significance and usage of this technology in safe long-distance flight and the major role the Sperry robot played during World War II.

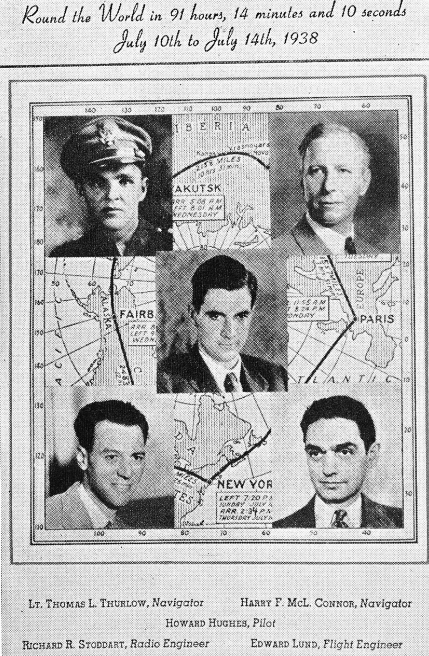

On July 4th, 1938, Heinmuller was called ‘on three occasions from my country home in Westchester County to time the take-off at Floyd Bennet Field as the official representative of the N.A.A.’[16] Howard Hughes’ take off was postponed on three occasions as Heinmuller waited in anticipation to time the record-breaking attempt:

The day finally came when everything was in readiness; and indeed, a state of readiness on that amazing flying institution was really something of an accomplishment, for it carried everything imaginable.

I had been sleepless for more than forty-eight hours, but I forgot to be tiered in the excitement of the last minutes, saying good-byes, wishing them luck and good flying, and, finally, shaking hands with each of the crew just before they took off. It was 7:20 P.M., July 10, when the big silver monoplane, truly a dream ship of the air, lifted her burden from the field.[17]

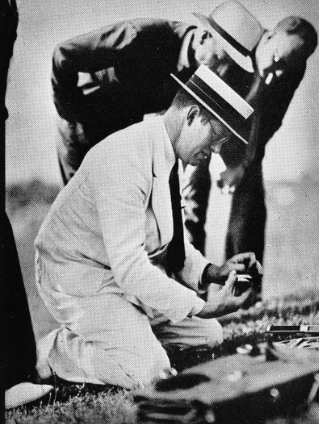

This would mark the successful take-off of Howard Hughes’ astonishing round-the-world flight of 1938. Heinmuller details the methods of his timing in which it was necessary to race down the runway alongside the plane in a speeding car. It was paramount that Heinmuller record the exact time at which the aircraft’s wheels left the concrete. This chase continued well after the relatively smooth surface of the runway onto the rough that extended beyond it.

This task was not without its dangers, being so terribly close to a plane during take-off could spell disaster if the vehicle should veer and crash. In fact, Hughes take-off was worrisome and as ‘the big plane crossed the first 100 yards of the rough field I was horrified to see that one of the huge wheels seemed to bend inward. It looked like the beginning of a disastrous crash, but after thirty seconds by the official stop-watch the plane emerged from a cloud of dust and began to rise slowly, passing out over Jamaica Bay.’[18]

Due to the sophisticated radio fitted by Hughes, Heinmuller was able to keep constant contact with the aircraft no matter where it was. Prior to this flight, radios had been characteristically cumbersome and temperamental, with many aviators choosing not to carry one at all. Hughes radio was a different machine altogether and Heinmuller recalls, ‘we had been left behind but we were with them. In our mind’s eye we saw them working over their maps and instruments; and we could picture Howard Hughes, remembering how he had casually gone aboard in wrinkled gray trousers, tan shoes, tan hat….’[19]

Howard Hughes tested a number of long distance instruments on this incredible circumnavigation of the globe in 3 days, 19 hours, 14 minutes and 10 seconds. They had traveled 14,672 miles and had ‘outdistanced the earth by one full lap in its whirl about its axis.’[20]

The axis was circled an incredible five times, as opposed to four, and the crew witnessed the sun set and rise five times in just four days between Sunday and Thursday. This was a fact which astounded Heinmuller who was fascinated by the science behind this phenomenon.

Contained within his detailed recordings are Hughes flight logs and various records kept by the crew. This detailed account serves to relay information whilst telling the tale so colorfully that the reader may imagine themselves in the cockpit with Hughes, or the speeding car with Heinmuller.

John P.V. Heinmuller was present, as an official timer, friend and confidant to many of aviation’s brightest pioneers. He was witness to some of the most historically significant flights during this Golden Age of aviation. His unfaltering dedication to the craft is well documented in the way he writes of such events, alongside the meticulous records he kept.

Captain Eddie Rickenbacker writes that the ‘necessity for accuracy has brought about the most stringent of rules by our governing bodies and our military services which must be supplemented by the character and ability of those charged with their enforcement. In all of these, my friend, John Heinmuller, has no peer.’[21]

Heinmuller committed his life to advancing aviation both in the name of commercial progress and national defense. Captain Eddie Rickenbacker further writes that Heinmuller’s ‘timepieces and navigation instruments have been an outstanding contribution to the successful operation in pioneering in air transport, and to our military services in time of war.’[22]

Man’s Fight to Fly

During the preface of Heinmuller’s Man’s Fight to Fly he states that ‘we are on the threshold of the “Air Age” and […] aviation will have unlimited possibilities if it is granted the means of progress.’[23]

He goes on to ask: ‘What can we offer as a sturdy foundation on which to build new air achievements? The answer is an accurate historical record of past accomplishments, with a brief introduction to the human side – who the pioneer aviator was, what he attempted and whether he succeeded or failed, all of which is published in this book.’[24]

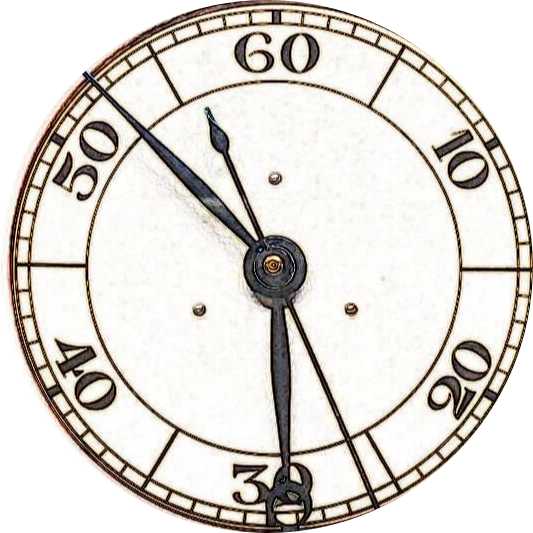

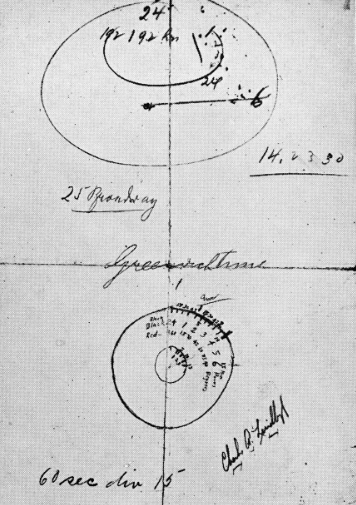

Without Heinmuller’s tireless efforts and passion towards aviation we would not have such a detailed and accurate understanding of this transformative period in history. With the wizardry of the technical department of Alfred Pfister et al at Longines, a wide range of specialist air navigation timepieces were born. His guidance, stewardship and commitment pushed the boundaries of what could be done. The Longines Weems second-setting watch was born with the input of Heinmuller and Weems. The latter is essentially the grandfather of today’s modern day GPS system.

This was improved upon when Lindbergh drew up his new Hour angle watch, adding units of the arc which allowed the calculation of longitude. Accurate timepieces regulated for sidereal time, the birth of the siderograph and a complex array of cockpit instruments and chronometers bought an ever-greater command of air navigation. Heinmuller, using a Longines, timed every aviation record, and he personally oversaw the organization and paperwork challenges to have these records recognized internationally.

Without question the golden age of aviation’s progress was one, if not ‘the’ most remarkable and defining parts of the twentieth century. It is a period that shaped us culturally, the way we think, interact, explore new places and society as a whole. In a developed country today, it is impossible to understate the role, experience, safety, progress and change that P.V.H Weems and John P.V Heinmuller and their commitment to those golden years of aviation brought to all of our lives.

Footnotes

- John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘IV Charles Augustus Lindbergh,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. 71.

- Anonymous, ‘Collectors: John P.V. Heinmuller,’ Arago: People, Postage and the Post,’ (Smithsonian National Postal Museum), http://arago.si.edu/category_2040919.html (date accessed: 02/09/16).

- Anonymous, ‘Collectors: John P.V. Heinmuller,’ Arago: People, Postage and the Post,’ (Smithsonian National Postal Museum), http://arago.si.edu/category_2040919.html (date accessed: 02/09/16).

- Anonymous, John P.V. Heinmuller, (Little Buttes Publishing Co.), http://littlebuttesbooks.com/blog/john-p-v-heinmuller (date accessed: 02/09/16).

- John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘IV Charles Augustus Lindbergh,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. 74-75.

- John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘IV Charles Augustus Lindbergh,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. 75.

- John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘IV Charles Augustus Lindbergh,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. 75.

- John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘III Richard Evelyn Byrd,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. 53.

- John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘III Richard Evelyn Byrd,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. 56.

- John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘III Richard Evelyn Byrd,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. 48.

- John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘VII Amelia Earhart,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. 119.

- Terry Gwynn-Jones, ‘Harold Gatty: Aerial Navigation Expert,’ Aviation History Magazine, (World History Group, September 2001), http://www.historynet.com/harold-gatty-aerial-navigation-expert.htm (date accessed: 19/08/16).

- John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘IX Wiley Post and Harold Gatty,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. 138.

- John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘IX Wiley Post and Harold Gatty,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. 138.

- John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘IX Wiley Post and Harold Gatty,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. 144.

- John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘XVI Howard Hughes,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. 216.

- John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘XVI Howard Hughes,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. 216.

- John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘XVI Howard Hughes,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. 216.

- [1] John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘XVI Howard Hughes,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. 217.

- John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘XVI Howard Hughes,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. 218.

- Captain Eddie Rickenbacker, ‘Foreword,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. xi.

- Captain Eddie Rickenbacker, ‘Foreword,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. xi.

- John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘Preface,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. xiv.

- John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘Preface,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. xiv.

Bibliography

Anonymous, ‘Collectors: John P.V. Heinmuller,’ Arago: People, Postage and the Post,’ (Smithsonian National Postal Museum), http://arago.si.edu/category_2040919.html

Anonymous, John P.V. Heinmuller, (Little Buttes Publishing Co.) http://littlebuttesbooks.com/blog/john-p-v-heinmuller

Gwynn-Jones. Terry, ‘Harold Gatty: Aerial Navigation Expert,’ Aviation History Magazine, (World History Group, September 2001), http://www.historynet.com/harold-gatty-aerial-navigation-expert.htm

Heinmuller, John P.V. Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945).

Rickenbacker. Captain Eddie, ‘Foreword,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945).