Wartime aviation was a dangerous pursuit for all involved, leaving little room for error with an ending mired in a tragic loss of life and wholesale destruction of property. The USAF archives upper estimate for Japanese ground and airborne plane losses in WWII is 50,000 units.[1]

A truly incomprehensible figure when all conflicts for the next 77 years note combined party aircraft losses of approximately 4000 units.[2] This makes the Imperial Japanese Navy’s Air Service Seikosha “Air Soldier” – Tensoku Dokei 天測時計 a rare and coveted Japanese military aviator watch.

Volumes have been written concerning the economic and human cost of war. The loss of at least 35,000 young Japanese pilots speaks to one small part of the human cost for one nation. This aside from the catastrophic effects of the nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the last days of WWII, where at least 150,000 people died in those two events alone. The scale of this destruction, loss of life, and property damage cannot be captured in any words.

This analysis makes no attempt to trivialize the suffering and losses, nor discuss events, outcomes or assign blame. For anyone with a special interest in horology, vintage military aviation watches are without exception some of the rarest and most sought-after ticking survivors.

Their rarity is of course attached to the extinction type outcomes of the pilot, plane, and their watch in early aviation history, especially during military engagement, and compounded by other unforeseen events post being issued.

It requires little imagination to grasp why there are so few survivors.

Longines had a remarkable association and unparalleled ownership in the production of specialist aviation watches for three plus decades in the first part of the 20th century. This led to the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service (IJNAS) choice of the Weems and the later production of the Tensoku for their pilots in WWII.

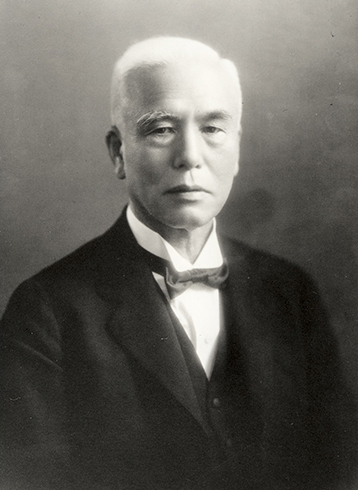

The Swiss company first sold movements and finished watches from 1911 to the “King of Timepieces in the East,”[3] Kintaro Hattori, and his company.

This business relationship and the latter’s success would have a substantial bearing on the choice of the Second-setting model for the IJNAS, and the birth of the famous Tensoku Dokei 47mm aviator model made by Daini Seikosha Co, an offshoot of Hattori & Co, in the latter part of 1940.

Multiple factors contributed to the latter’s success, including: favourable Japanese customs practices that supported a substitution industry and protectionism.

A significant expansion of Hattori’s technological know-how following studies of the construction of these imports and the profits that flowed from sales of Longines and other Swiss imports.

Hattori was not interested in progressing watch-related innovation, nor developing watchmaking techniques. Instead he focused on adopting high-precision Swiss reference models, primarily Nardin and Longines watches[4], whilst developing and improving their technical skills. Following business trips abroad he employed technological hybridization[5], combining the American mass production model with the precision and innovation of the Swiss and Germans.

Kintaro passed away in December 1934 at the age of 73 after playing the greatest role in the invention, development, and progression of the Japanese watch and clock industry post the Meiji period. His legacy, Hattori & Co, surpassed its main American and Swiss competitors becoming the largest watch producer in the world.

The Japanese product was equivalent to, or at times, superior to their rivals. This was first noted October 1933,[6] in the findings of an internal report by the Allgemeine Schweizerische Uhrenindustrie AG (ASUAG),the Swiss holding company controlling production of watch movements.

It was confirmed for a second time by the same association after tests in Le Locle on fourteen watches including nine from Hattori. The Swiss embassy in Tokyo secured samples for retesting in January 1934, reconfirming the earlier evaluation.[7]

Aside from Hattori, substantial credit lies with Professor Aoki Tamotsu, who was instrumental in the transformation of the Japanese watch industry. Working with the engineering faculty of the University of Tokyo, and the Horological Institute of Japan (Nihon tokei gakkai), they recognized the need for specialist horology artisan training by setting up a Precision Industry High School (Koto seimitsukogakko) in 1933.

Key improvements followed in precision watch and other specialist engineering faculties after Aoki visited 84 international factories over five months in 1935.

The professor recognized the need for production engineers in a variety of key core industries and sectors.[8] Aoki also headed The Tokyo University Department of Arms Production (zohei gakka), the so called DAP, which post war, was renamed the Department of Precision Engineering (seimitsu kikai kogakka).

During the 1930’s the Swiss formed watch cartels applying trading restrictions on parts and the supply of raw materials, components, and equipment. This punished the Japanese for their trade practices, leading to a ban in 1931 of certain exports to Japan. Parts and later whole watches were smuggled through other countries bypassing the impact of the cartel’s activities. However, technological restrictions would later become an obstacle to Hattori’s development. [9]

The Japanese were successful at indirect and parallel importation. Their entire order of IJNAS Longines Weems pieces received in 1937 and 1940 were delivered via America. Movements were stamped LXW indicating US importation with archives also noting delivery to Wittnauer. These orders then made their way to the home of the cherry blossom for a conflict that would soon involve America post what Roosevelt termed, “..a day of infamy”.

Named after the Japanese invasion of the northeastern provinces of China, the ‘Manchurian Incident’ of 18th September 1931, marked the start of Japan’s aggressive Asian expansion, clouding the skies. The second Sino-Japanese war of July 1937 brought eight years of continuous conflict, sowing the seeds for world war. Further export bans, sanctions, boycotts and trading restrictions were placed by the Americans, Swiss and others on petrol, steel, whole watch and parts sales to Japan.

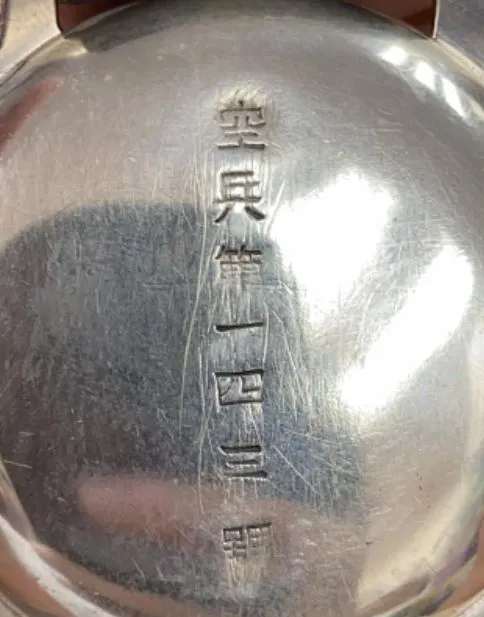

The Japanese have no equivalent word for Air Force. The caseback of both the Longines Weems and the Seikosha pilot pieces that followed feature the Kanji characters (空兵). This literally translates to ‘Air Soldier’, along with a Japanese character for dai (a prefix for number), with the actual issue number.

The first specialist IJNAS watch arrived in the form of the Longines Weems. A delivery of twenty ref 5350 Type – A3 all silver Weems watches with pin-set calibre 18.69N was made on September 17, 1937, just two months after the start of the Second Sino-Japanese war. Whilst others may possibly exist, this is the rarest ‘Air Soldier’ watch. Archives note fewer than fifty produced with just three known surviving examples over the last 25 years – Air Soldier #121, #131 and #143.

Distinct to this model, the Kanji characters run in a single line down the middle of the back case. This can be contrasted with the two separate lines of case characters used on the IJNAS steel Weems and Tensoku models that followed in 1940.

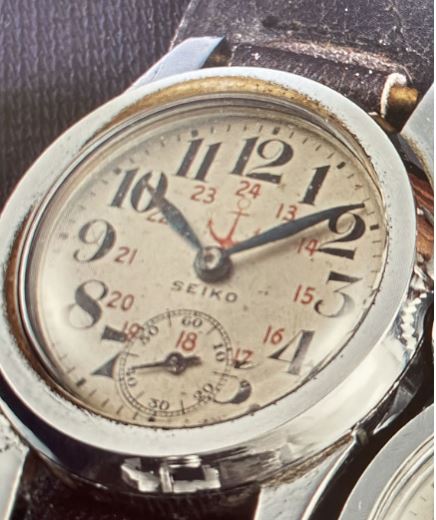

These first 1937 Weems deliveries coincided with the founding of Daini Seikosha Co. which was a Hattori subsidiary. They soon became a major 20th century Japanese manufacturer of components and watches, supplying base metal chrome plated manual wind timepieces with different dial notations for their growing military needs.

Pieces for the navy featured an anchor, a star for the army, and a cherry blossom with radium hands and dial markings for the air force, albeit the dial feature was absent on the Tensoku. Daini had no interest in innovation and continued to copy and model both Longines and Nardin movements alongside other watch making machinery.

They dramatically expanded the employment of specialist production engineers, and by 1943 had created 500[10] marine chronometer clones of a 1930’s Ulysee Nardin model previously supplied to Hattori.

Daini’s wartime production peaked in 1940 at 1.3 million units, with five issued watches supplied to the army and navy. In June of the same year, the last known Longines Weems delivery was made. The second and final iteration of the Longines ‘Air Soldier’ Weems preceded the introduction of the famous large brass nickel case Seikosha Tensoku.

These Weems Type A-12 military pieces for the IJNAS arrived in stainless steel cases bearing ref 4356, and account for the majority of known examples. There are just a handful or two surviving. This reference used a 37.9 calibre and featured a second crown at four to adjust the second-setting function. A total order of approximately 400 pieces were delivered on at least three separate dates in 1940. Two of these known orders were regulated for either sidereal (order #20852), or civil time (#20853) with the last known receipt being June 21st, 1940.

Watches regulated for sidereal time are generally used with a second timepiece running civil time. The consecutive order numbers of these two Longines IJNAS Weems deliveries seemingly point to this. When supplied, their sidereal dials had red stars at 3 and 9 which indicated adjustment for star time.

Any post war watch survivors were likely considered prizes of the victor, and the few known found their way to America. The McCarthyism era that followed ensured the majority of red stars were crudely removed by a watchmaker who wrongly feared some communist association.

The oversized Tensoku 47mm aviator watch is the most famous production model of Daini Seikosha Co. and was first introduced with a 15-jewel movement that was stamped as such. Quality was downgraded over the course of the war due to 9 and then 7 jewels due to supply constraints. Whilst information exists concerning delivery details for the Longines IJNAS Weems that also includes the type of regulation, there is no exact information concerning the exact date of delivery nor regulation of the Tensoku Dokei.

All evidence points to consecutive numbering on the delivery of all watches issued by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service. At the moment the highest known Longines Weems IJNAS precursor has #1403 as an issue number. Whilst issue numbers on the Tensoku have been seen as high as 7xxx, the lowest seen so far is #582.

The Weems arrived earlier and consequently almost all bar one has surviving numbers less than 1000. Given the precarious state of the Japanese in the latter stages of war, in 1945 military pieces including the Tensoku were supplied without numbering and have plain unmarked case backs. The exact number made remains a mystery, however, consecutive numbering puts total production of all IJNAS watches of all kinds at less than 10,000 units with the Tensoku an unknown portion of this.

The Japanese long name for this famous creation, Tensoku Tokei (天測時計) notes a celestial navigation timepiece. The meaning also shares a relationship to the principle of maintaining the order of the universe, including the operation of celestial bodies, the order of the natural world, and also the way rituals and humanity should be. This includes the requirement that both God and people needed a vow to keep these rules.

Given the time of their arrival, the Imperial Japanese Navy’s Air Service branch (IJNAS) most likely used them in battles across the pacific, including the Philippines, Guadalcanal, Pearl Harbour, and Midway. Whilst the model developed a reputation among early collectors that it was used by Kamikaze pilots, this is unlikely to be the case.

Whilst some suicide attacks may have been launched by a Japanese pilot who originally set-off with a different purpose, most were pre-planned from the outset. Of the 2800-4000[11] estimated Kamikaze missions, the use of a stripped-down plane would largely negate the needs for specialist precious navigation equipment and the famed Air Soldier timepiece wrist companion.

It is important to note similarities in the DNA of both the Weems and Tensoku models. They were oversized, sported an onion crown and production used pocket watch base calibres. The second-setting Longines model used the 18.69N and 37.9 calibres, while the Daini creation, a manual wind oversized 19 ligne movement made with 7,9 or 15 jewels.

Hattori had 45 plus years’ experience building pocket watch movements, having first introduced its Timekeeper branded pocket watch in 1895. There were two variations of the inner chapter ring on the Tensoku with the first having red division marks that extended to the edge of the numbering scale. They were shortened on the second-generation pieces.

Given that Hattori skills were significantly developed in this manufacturing space; it is highly likely Daini wanted a model on which to base their Tensoku aviator watch. The turning bezel with inner chapter was not dissimilar to the Weems and their primary difference the dials, a black radium metal dial versus the grand feu enamel version.

Daini Seikosha’s past movement cloning history and the UN marine chronometer copies that appeared in 1943, lend weight to this assertion and lend support to reasons why the famous Longines Weems model was chosen.

The Hattori company were importing Swiss watches from 1886, had a longstanding agency and import relationship with Longines from 1911. The latter’s prowess and history in making aviation pieces and the accuracy and precision of their movements was well known.

There may also have been an interest in exploring steel case technology. Pre WWII, the majority of Seikosha watches were metal with a sprinkling of steel cases. It is unknown if these steel cases were actually made or just stamped by them. So called Staybrite steel was also protected under a Swiss patent by Thomas Firth in 1934 and required specialist machinery.

Longines were the only producer of the large Weems model, had the technical equipment, technology and also the available materials for making steel watches and that likely interested Daini. The St Imier company supplied a few rare steel oversized wrist chronographs with enamel dials and a 15 ligne valjoux base calibre to Hattori in October 1935, one of the last known direct deliveries. These specialist pieces with a 40mm case bearing ref 3205, were likely destined for the military along with complete pocket watch chronographs and raw movements supplied in the mid 1930’s.

The Tensoku’s brass case was nickel plated and likely chosen because of available materials and the absence of the necessary tooling to work with stainless steel. The Seikosha output was impressive, and they were the only Japanese watchmaker capable of meeting wartime production needs.

However, the limits of war time itself led to potential material shortages, Swiss parts embargoes and materials being channeled into other military equipment manufacture. The availability of materials and restrictions on access to new tooling equipment and technology ensured that Daini’s production of steel watches came post war with perhaps the odd anomaly.

Raw material supplies were an issue for the Japanese given the extended nature of their aggression in China and elsewhere. Typically, military watches are made in quantity, and from available and at times lower grade materials. Whilst materials and watches were more available in the early stages of war, seemingly not all Imperial Japan military personnel were issued timepieces. Given the eight years of continuous war for Japan, supply issues abounded on multiple fronts.

Little is known about the Japanese military process for their issued watches in WWII. Some possible understanding comes from other countries. All watches had to be returned to the military once the soldier retired from service. The markings on the British Air force watches were added by the Ministry of Defence (MOD) contrary to their army watches which were done by the Swiss suppliers.

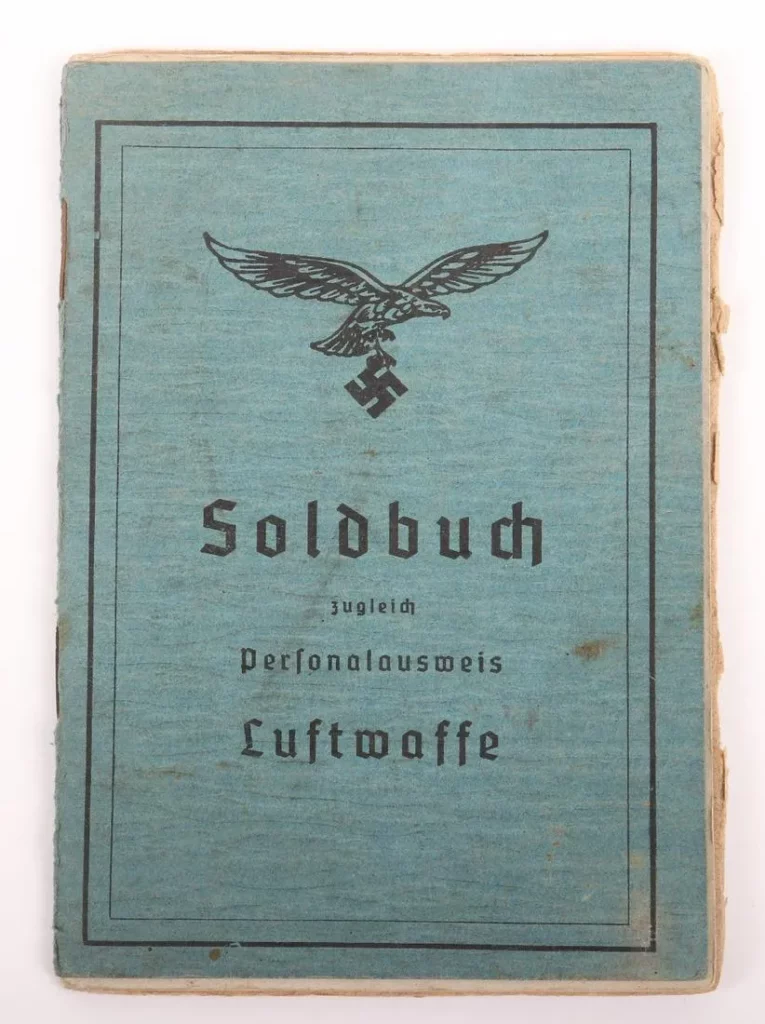

German army watches were given to the individual soldier and entered into his soldbuch (identity papers), together with any other equipment he was issued with, and they remained Wehrmacht (army/defence force) property. The soldbuch contained passport information, and included extra details about the soldier, including their rank, regiment/unit assigned to, equipment used, issued, and dates of leave.

However, pilot’s observers’ watches (IWC, Laco, Lange, Stowa and Wempe) for the Luftwaffe were issued each day of use. Upon the return from their sortie the pilots and navigators were debriefed, returning their watches which were then reassigned to the next flying mission.

In all likelihood, this, or a similar process was most likely used by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service for both the Tensoku and Weems issued watches. The IJNAS oversaw naval aviation and was led by the Chief of the Navy Aeronautical Department (海軍航空部長, Kaigun Kōkū-bu-chō). The question of who or which department added the Kanji case back markings to all IJNAS pieces back remains a mystery.

The Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service issued watches are without exception among the very rarest special military watch of all nations. The Seikosha factory production facilities were completely destroyed at the end of WWII and later rebuilt.

The scale of catastrophic devastation wrought by the nuclear bombing of the archipelago as WWII neared an end, coupled with the sustained Japanese air losses over the five years of conflict from the Tensoku’s arrival, have ensured many a collector will never see, nor own one.

There may still be the odd piece awaiting discovery in a collection in Japan or America (taken at the end of the war). However, finding a beautiful original Japanese Tensoku Dokei is like discovering a pair of mating dodo birds in the backyard.

Kintaro Hattori first sowed the seeds more than 120 years ago for the juggernauts, Daini Seikosha Co. Ltd, and sister company Suwa Seikosha Co. Today, they have morphed into distinct Seiko entities, and are moving parts of one of the most recognized international global brand names in the world. The legendary Tensoku still takes to the skies for the odd lucky individual and flies high in the eyes of collectors.

[1] WWII Aircraft Losses By Country – World War Wings

[2] WWII Aircraft Losses By Country – World War Wings

[3] Seiko Museum online Development of the Japanese Timepiece Industry centered by Seikosha | THE SEIKO MUSEUM GINZA

[4] The hybrid production system and the birth of the Japanese specialized industry: Watch production at Hattori & Co. (1900-1960)”, Enterprise & Society, vol. 12 no.2, 2011, p 361 | Pierre-Yves Donzé – Academia.edu

[5] “The hybrid production system and the birth of the Japanese specialized industry: Watch production at Hattori & Co. (1900-1960)”, Enterprise & Society, vol. 12 no.2, 2011, p 366 | Pierre-Yves Donzé – Academia.edu

[6] The hybrid production system and the birth of the Japanese specialized industry: Watch production at Hattori & Co. (1900-1960)”, Enterprise & Society, vol. 12 no.2, 2011, p 370 | Pierre-Yves Donzé – Academia.edu

[7] The hybrid production system and the birth of the Japanese specialized industry: Watch production at Hattori & Co. (1900-1960)”, Enterprise & Society, vol. 12 no.2, 2011, p 370 | Pierre-Yves Donzé – Academia.edu

[8] The Department for Arms Production of the University of Tokyo and the beginnings of the Japanese precision machine industry (1930-1960), Osaka Economic Papers, 2011 | Pierre-Yves Donzé – Academia.edu p42

[9] “The hybrid production system and the birth of the Japanese specialized industry: Watch production at Hattori & Co. (1900-1960)”, Enterprise & Society, vol. 12 no.2, 2011, p 372 | Pierre-Yves Donzé – Academia.edu

[10] The hybrid production system and the birth of the Japanese specialized industry: Watch production at Hattori & Co. (1900-1960)”, Enterprise & Society, vol. 12 no.2, 2011, p 375 | Pierre-Yves Donzé – Academia.edu

[11] The Divine Wind: Japan’s Kamikaze Pilots of World War II by Author Saul David, PhD | The National WWII Museum | New Orleans (nationalww2museum.org)

I recently ( in a watch trade) acquired a Seikosha Japanese Airforce watch. 30mm double cased. The watch runs and keeps time. Only markings on the case back are those of Seiko.

Can an expert here educate me about this watch.

Cheers in advance Robert

Greetings Robert… if you email a pic (not sure if can attach here) or to info@flightbirds.net or andy_timeman@yahoo.com I will try my best to give you any insights if known. Andy 🙂

Fascinating. Your research is terrific. I have been trying to educate myself about this ref. 5350 A3 model. Do you have any notion of how many 5350 A3’s were made in total? I have one, which is two digits infront of the one which was owned by Amy Johnson, which was auctioned by Sotheby’s.

Greetings Brett and many thanks for your feedback and comments. It makes it all worthwhile. There were far more Weems models produced than the hour angle. That being said there were not many of either. The first Weems arrived in November 1928 and was the personal watch of Weems. The first production pieces (72 pieces) were ordered in 1929 by Wittnauer and delivered April 10 and May 2, 1930. I have a letter from Weems to Heinmuller months later asking whether any success in selling them. A further 180 pieces were delivered to Wrightfield Ohio in April 1931, and first production hour angle November or December 1931. Following that there really are a few stragglers up until 1937 including Byrd’s one in 1933 and a couple of single deliveries to Germany including a single known Chrome cased hour angle piece that I have. The Great Depression was absolutely brutal on sales and Martha Wittnauer essentially staved off Bankruptcy only because Longines established new Longines-Wittnauer company in 1936 and from mid 1935 we see the dials carry both Longines and Wittnauer. Almost all the second setting Weems delivered to Wittnauer and almost all hour angle a multitude of destinations. By mid 1930’s we see first glimpses of radar navigation. Is your 5350 regulated for sidereal or civil time? Andy 😉

dzar Sirs

as military watch collestor I would be pleased to know aproximately how many seikosha tensoku warches were prodiced and if pssible split into de difent forms strab, pocket and cockpit

Best regards

Greetings and the sincerest of apologies for a belated reply. The highest numbered piece is around 7000 and others in 1945 made without numbering. However, evidence seems to point to some form of consecutive numbering for other IJNAS pieces. The Longines Weems watches of which approximately 400 seemingly feature in this lineup of 7000 with the majority having a number less than 1000 and likewise the earliest known Tensoku number is from memory and research around 500plus (thanks to Seiji Kamiya for his help in this space). This likely indicates the IJNAS numbered pieces of Longines PW, the IJNAS Weems wrist, Tensoku and other variations as they came into service. Andy

Wonderful article & some stellar research thank you for sharing this information on one of the lesser know areas of military horological history.

Where are you based the Fratello article mentioned you are in Australia?

Greetings Rick and many thanks for your feedback mate. It makes it all worthwhile writing. I am an English born runaway Aussie living in Asia that went down one too many rabbit holes. Where are you mate? Andy 😉