After Howard Hughes’ world circling flight of 1938, he proclaimed to Harold Gatty, pioneer, ‘Greetings and gratitude, trail-blazing pioneer. We only followed where you led.’[1]

Hughes could not have summed up the life and contribution of this incredible navigator and aviator more succinctly. A pioneer and ingenious inventor in his field, Gatty, enabled some of the most exceptional flights during this Golden Age of aviation.

He developed new technologies that allowed blind flight, a concept hitherto terrifying for pilots and navigators alike. In thick ‘pea-soup fog’[2]

The Winnie Mae Around the World

Gatty was able to traverse the skies with skill and precision, using a variety of instruments and techniques, to pinpoint his exact position. The skill of this man was unparalleled.

His intricate and studious knowledge of celestial navigation guided the infamous Winnie Mae flight, Around the World in Eight Days. He was a navigator like no other who passed his learning and knowledge onto countless others through generous teaching. Gatty, perhaps more than any other, pioneered new methods and technologies which propelled both navigation and aviation into the future.

It was Gatty’s love of the stars which led him toward his trailblazing career in navigation. He stood night watch upon a steamship, a cadet officer, as part of the Australian Merchant Navy.

During this time he studied the skies, later remarking: ‘I suppose my imagination was appealed to by the stars and the moon which play such an important part in navigation. I spent many nights watching the stars. I soon reached a stage where I could tell the time by the position of the stars in the heavens. I learned the changes in their positions in the various seasons of the year.’[3]

Gatty continually advocated this crucial mode of navigation, alongside other natural methods. His students learned how to navigate by the sun and stars, as well as how to understand and apply drift over the ocean.

These tried and tested methods are still taught to aviators today. Well before pilots enter an aircraft fitted with an electronic flight instrument system it is required of them to understand the method behind each instrument and how to utilize these should equipment fail.

Gatty’s inventions revolutionized navigational techniques. He began with ‘an air sextant that used a spirit level to provide an artificial horizon. Next he produced an ‘aerochronometer’ that offset the inaccuracies that aircraft speed produced when a flier was taking a navigational observation. His most important contribution, however, was the Gatty drift sight, which he refined into a superb ground speed and drift indicator widely used by airmen during the late 1930s and eventually sold to the U.S. Army Air Corps.’[4].

To the USA

After emigrating from Australia Gatty settled in Los Angeles and opened his school for navigators. This venture began primarily with the tutelage of marine navigation to yachtsmen. Soon his attention turned to aviation and, in particular, navigation during long distance flights over sea. There was no formal method yet in place for aerial navigation. This had often resulted in the tragic deaths of numerous pilots.

Helping Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh

In the midst of preparing for his own transpacific flight with Harold Bromley, Gatty was approached by Anne Morrow Lindbergh. Her husband had used Weems curves during his famous transatlantic crossing and had been recommended as a top notch navigator by Lt. Cmdr. Philip Charles Weems.

The inventor of the Weems curve method and Gatty had previously collaborated on navigation technique. Gatty so impressed Weems that he was asked to teach at his own San Diego school.

Anne Morrow Lindbergh was to serve as navigator to her husband, Charles Lindbergh, on his upcoming transcontinental flight in the new Lockheed Cirrus. Gatty was asked by Lindbergh to prepare Weems curves and maps for the flight.

She benefited also from his tutelage and expertise remarking upon return: ‘I was very much surprised at how easy it was to take the sights and how quickly and easily one could use the curve and transfer it onto the mercator chart and, finally, how increasingly good the lines of position turned out to be….Thank you very warmly for everything you did to help us (including the plotting board and your kind word of encouragement, and for our two very absorbing and interesting weeks of work).’[5] In 1930 the Lindbergh’s successfully crossed the continent in 14 hours and 45 minutes. Gatty played no small part in their success and was named the ‘Prince of Navigators’[6] by Charles Lindbergh himself.

Crossing the Pacific

Gatty’s own transpacific flight with Harold Bromley was to end in disaster with the mission aborted and both men poisoned by a carbon monoxide leak not long after take-off. Gatty collapsed three days after the fated flight and suffered for several weeks in a Tokyo hospital with carbon monoxide poisoning.

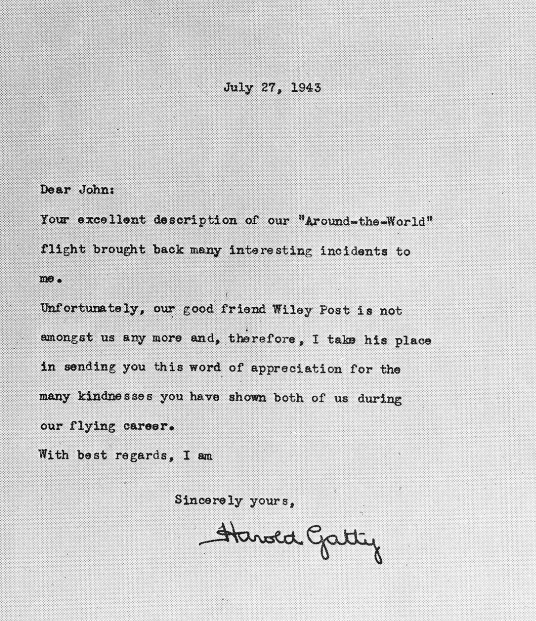

Around the World with Wiley Post

His big success was to come in 1931 navigating the infamous Winnie Mae with, one eyed pilot, Wiley Post in the very first round the world flight. Popular Mechanics in September 1931 laid out the difficulties of ‘”shooting the sun” from an airplane averaging 100 miles an hour… The position of the plane changes so rapidly that the reckoning becomes most difficult… the adventure offered a daring challenge to both men and aircraft… (and)… a decisive test to the instruments by which men steer across seas and continents.’[7]

Gatty and Post flew blind a few hundred miles from the coast of England. At 12,000 feet the men relied upon Gatty’s expertise to guide them through ‘pea-soup fog.’[8] Gatty had his own devices on board, one of his ‘chief pleasures was testing his own invention of a ground speed and drift indicator, combined into one instrument.’[9] His invention proved incredibly useful and the ‘instrument won his confidence.’[10]

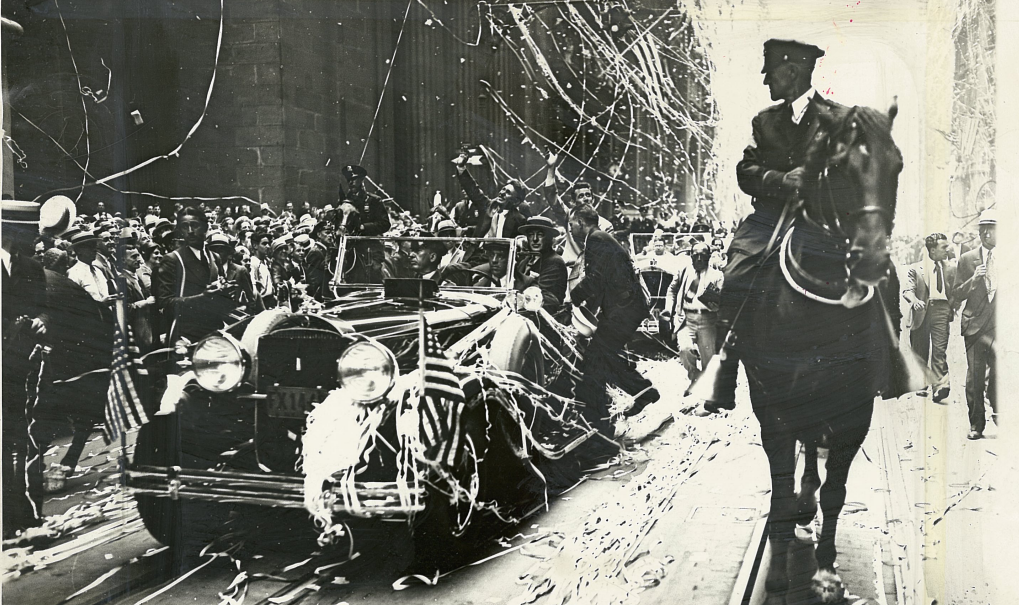

They touched down on Roosevelt Field eight days later to an overwhelming crowd cheering for their arrival. A ticker tape parade was held in New York to honor the men as heroes. Gatty and Post went on to receive the Distinguished Flying Cross from President Herbert Hoover. The award honoring him for “his intrepid courage, remarkable endurance, and matchless skill materially advancing the science of aerial navigation.”[11]

Australian born Gatty was offered American citizenship however, proud of his heritage, he turned it down. Congress went on to pass a special act so that Gatty could take up the post of senior aerial navigation engineer for the U.S. Army Air Corps without American Citizenship. He was a navigator in high demand.

A Career with Pan Am

Gatty was working with Pam Am when he was approached by Howard Hughes in 1937. He received a cable from the eccentric billionaire asking for his assistance in his up and coming round the world flight. He envisaged Gatty as his chief navigator in the Lockheed 14. While the offer was tempting, Gatty turned Hughes down to concentrate on his work with Pan Am. He did however offer assistance and advice that Hughes gladly took. Three of Hughes four crew members were personally recommended by Gatty.

The War Years

World War II struck and Gatty was appointed as an honorary Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) group captain working with Lt. Gen. George H. Brett, commander of the U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) in the South Pacific. Gatty coordinated the aerial evacuation of countless civilian refugees and soldiers from Java. He went on to coordinate and execute a number of crucial operations for both the RAAF and USAAF throughout the war.

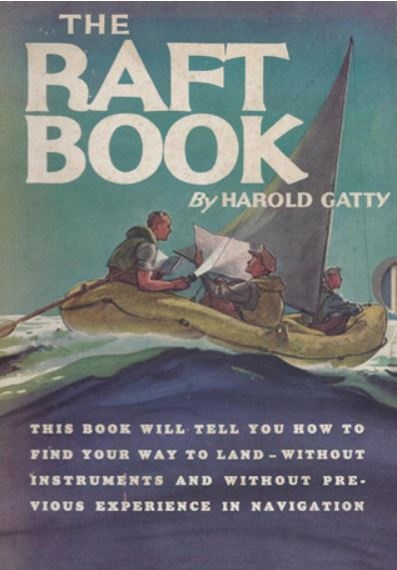

He resigned from this post and on return to Washington wrote The Raft Book. This manual detailed how to survive should you be stranded at sea.

Designed for Navy airmen, he explained how to navigate in a dinghy with limited supplies and equipment.

The book, an incredible success, was included in the survival kits of all allied airmen serving in the Pacific.

Born on the 5th of January 1903 in Campbell Town, Tasmania, Harold Gatty went on to live a truly extraordinary life. He broke records, invented and developed revolutionary navigation instruments and techniques, he passed on his knowledge willingly and dutifully and served during WWII; The Raft Book saving the lives of downed Navy airmen.

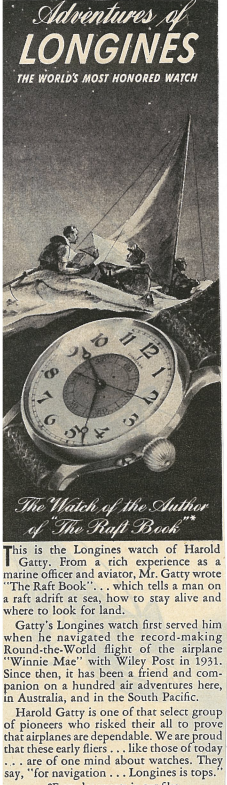

His contributions to aviation are vast and inconceivably valuable. In 1957, at just 54, Gatty died of a stroke after settling in Fiji. He will forever be remembered as ‘one of that select group of pioneers who risked their all to prove that airplanes are dependable.’[12]

Footnotes

- Terry Gwynn-Jones, ‘Harold Gatty: Aerial Navigation Expert,’ Aviation History Magazine, (World History Group, September 2001), http://www.historynet.com/harold-gatty-aerial-navigation-expert.htm (date accessed: 19/08/16).

- Popular Mechanics, Into the East Out of the West, Around the World: What Aviation Needs, Popular Mechanics, Vol. 56, No. 3 (Hearst Magazines, Sep 1931), pp. 354.

- Terry Gwynn-Jones, ‘Harold Gatty: Aerial Navigation Expert,’ Aviation History Magazine, (World History Group, September 2001), http://www.historynet.com/harold-gatty-aerial-navigation-expert.htm (date accessed: 19/08/16).

- Terry Gwynn-Jones, ‘Harold Gatty: Aerial Navigation Expert,’ Aviation History Magazine, (World History Group, September 2001), http://www.historynet.com/harold-gatty-aerial-navigation-expert.htm (date accessed: 19/08/16).

- Terry Gwynn-Jones, ‘Harold Gatty: Aerial Navigation Expert,’ Aviation History Magazine, (World History Group, September 2001), http://www.historynet.com/harold-gatty-aerial-navigation-expert.htm (date accessed: 19/08/16).

- Terry Gwynn-Jones, ‘Harold Gatty: Aerial Navigation Expert,’ Aviation History Magazine, (World History Group, September 2001), http://www.historynet.com/harold-gatty-aerial-navigation-expert.htm (date accessed: 19/08/16).

- Popular Mechanics, Into the East Out of the West, Around the World: What Aviation Needs, Popular Mechanics, Vol. 56, No. 3 (Hearst Magazines, Sep 1931), pp. 353.

- Popular Mechanics, Into the East Out of the West, Around the World: What Aviation Needs, Popular Mechanics, Vol. 56, No. 3 (Hearst Magazines, Sep 1931), pp. 354.

- Popular Mechanics, Into the East Out of the West, Around the World: What Aviation Needs, Popular Mechanics, Vol. 56, No. 3 (Hearst Magazines, Sep 1931), pp. 356.

- Popular Mechanics, Into the East Out of the West, Around the World: What Aviation Needs, Popular Mechanics, Vol. 56, No. 3 (Hearst Magazines, Sep 1931), pp. 356.

- Andrew K. Johnston, Roger D. Connor, Carlene E. Stephens, Paul E. Ceruzzi, Time and Navigation: The Untold Story of Getting from Here to There, (Smithsonian Books, 2015), pp. 87.

- Adventures of Longines, ‘The Watch of the Author of “The Raft Book,”’ LIFE, (Time Inc, 10 April 1944), pp. 100.

Bibliography

Adventures of Longines, ‘The Watch of the Author of “The Raft Book,”’ LIFE, (Time Inc, 10 April 1944).

Johnston, Andrew K. Connor, Roger D. Stephens, Carlene E. Ceruzzi, Paul E. Time and Navigation: The Untold Story of Getting from Here to There, (Smithsonian Books, 2015)

Terry Gwynn-Jones, ‘Harold Gatty: Aerial Navigation Expert,’ Aviation History Magazine, (World History Group, September 2001), http://www.historynet.com/harold-gatty-aerial-navigation-expert.htm (date accessed: 19/08/16)

Time and Navigation, ‘Meet the Navigator: Harold Gatty,’ Navigating in the Air, (Smithsonian), https://timeandnavigation.si.edu/navigating-air/early-air-navigators/two-men-in-a-hurry/harold-gatty (date accessed: 19/08/16)

[1] Terry Gwynn-Jones, ‘Harold Gatty: Aerial Navigation Expert,’ Aviation History Magazine, (World History Group, September 2001), http://www.historynet.com/harold-gatty-aerial-navigation-expert.htm (date accessed: 19/08/16)

[2] Popular Mechanics, Into the East Out of the West, Around the World: What Aviation Needs, Popular Mechanics, Vol. 56, No. 3 (Hearst Magazines, Sep 1931), pp. 354.

[3] Terry Gwynn-Jones, ‘Harold Gatty: Aerial Navigation Expert,’ Aviation History Magazine, (World History Group, September 2001), http://www.historynet.com/harold-gatty-aerial-navigation-expert.htm (date accessed: 19/08/16)

[4] Terry Gwynn-Jones, ‘Harold Gatty: Aerial Navigation Expert,’ Aviation History Magazine, (World History Group, September 2001), http://www.historynet.com/harold-gatty-aerial-navigation-expert.htm (date accessed: 19/08/16)

[5] Terry Gwynn-Jones, ‘Harold Gatty: Aerial Navigation Expert,’ Aviation History Magazine, (World History Group, September 2001), http://www.historynet.com/harold-gatty-aerial-navigation-expert.htm (date accessed: 19/08/16)

[6] Terry Gwynn-Jones, ‘Harold Gatty: Aerial Navigation Expert,’ Aviation History Magazine, (World History Group, September 2001), http://www.historynet.com/harold-gatty-aerial-navigation-expert.htm (date accessed: 19/08/16)

[7] Popular Mechanics, Into the East Out of the West, Around the World: What Aviation Needs, Popular Mechanics, Vol. 56, No. 3 (Hearst Magazines, Sep 1931), pp. 353.

[8] Popular Mechanics, Into the East Out of the West, Around the World: What Aviation Needs, Popular Mechanics, Vol. 56, No. 3 (Hearst Magazines, Sep 1931), pp. 354.

[9] Popular Mechanics, Into the East Out of the West, Around the World: What Aviation Needs, Popular Mechanics, Vol. 56, No. 3 (Hearst Magazines, Sep 1931), pp. 356.

[10] Popular Mechanics, Into the East Out of the West, Around the World: What Aviation Needs, Popular Mechanics, Vol. 56, No. 3 (Hearst Magazines, Sep 1931), pp. 356.

[11] Andrew K. Johnston, Roger D. Connor, Carlene E. Stephens, Paul E. Ceruzzi, Time and Navigation: The Untold Story of Getting from Here to There, (Smithsonian Books, 2015), pp. 87.

[12] Adventures of Longines, ‘The Watch of the Author of “The Raft Book,”’ LIFE, (Time Inc, 10 April 1944), pp. 100.