Admiral of the Antarctic, Admiral Richard Evelyn Byrd, leaves in his wake an inspiring legacy of daring, adventure and triumph.

As a distinguished Naval Officer, pioneering American aviator and Polar explorer, Byrd received twenty-two citations and special commendations throughout his life.

Nine of these were awarded for bravery and two for extraordinary heroism when rescuing others. Richard Byrd is a member of the Longines Honor Roll.

When asked by Larry LeSuer of CBS television what he found to be the most valuable quality needed for expedition, Byrd simply responded, “Well I’ve always thought that loyalty was by far the most important trait.”[1]

During this particular episode of the Longines Chronoscope, Byrd reiterated that the trust of one’s crew is paramount.

His loyalty and heroism are recognized through medals, awards and more significantly; through the teams he led, the rescue missions he commanded and the lives he saved. It was recognized by all those who served with Byrd, throughout his extraordinary life.

Born on October 25, 1888, Byrd went on to explore, discover and map the unforgiving extremities existing at either ends of the earth. Icy deserts boasting temperatures seventy degrees below zero with cruel gales that rattle along glaciers at up to 130 mph.

Widely unexplored by the Western World, the North and South Poles became exciting exploits for aviators around the world. To discover untapped resources, to claim and name un-mapped land and to push man into the limitless possibilities of the great unknown quickly took hold of public imagination in the wake of WWI.

Through a number of dangerous expeditions, Byrd, along with fellow pioneers of aviation, paved the way for modern commercial flight, advanced radio communication, navigation and scientific discoveries previously unknown to man.

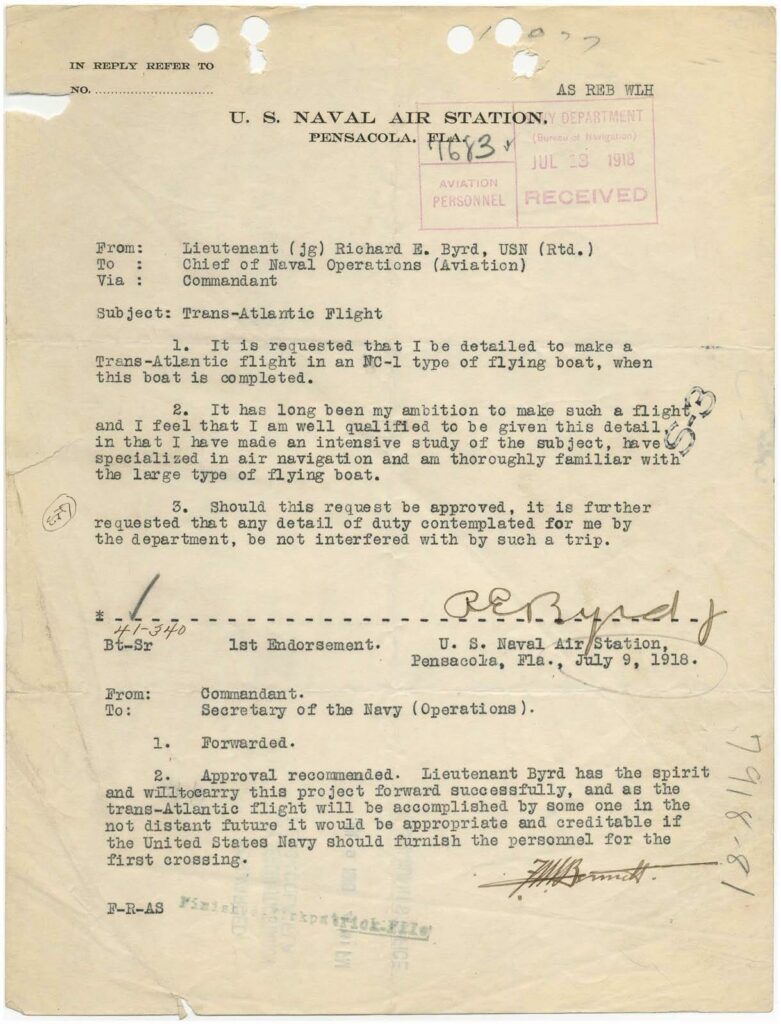

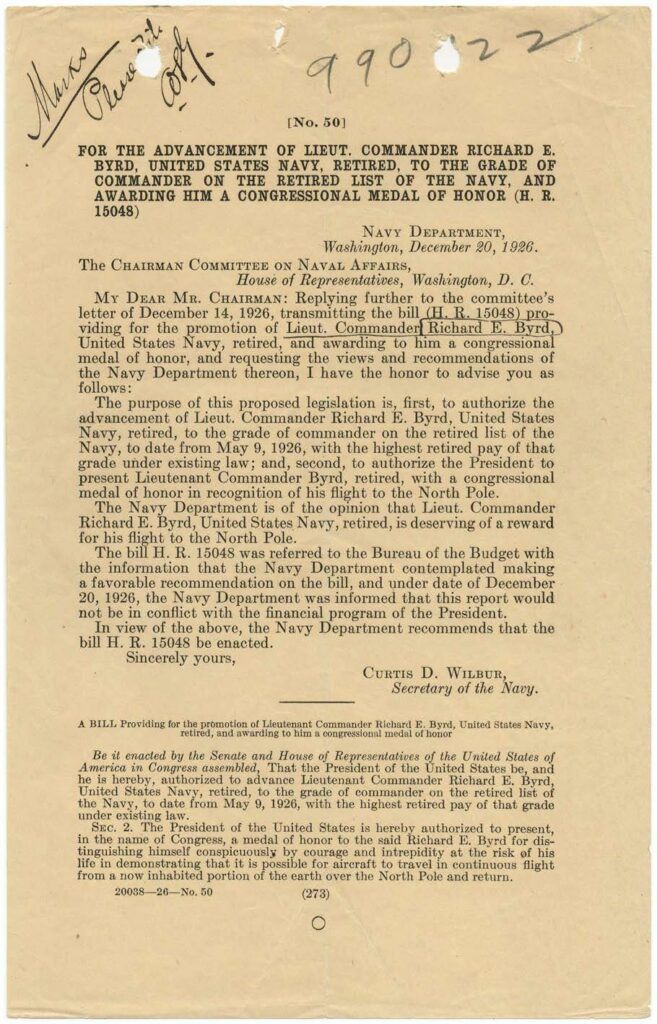

On May 9, 1926, in a Fokker F.VIIa/3m Tri-motor monoplane named Josephine Ford, it is believed that Byrd and Floyd Bennet were the first to fly over the North Pole.

There has been some controversy over this claim with critics disputing its legitimacy. The flight lasted fifteen hours and fifty-seven minutes, covering a distance of 1,535 miles.

Upon his return to America Byrd became a national hero. Both he and Bennet were promoted in Naval rank and awarded the Tiffany Cross Medal of Honor. These were presented at the Whitehouse on March 5th by President Calvin Coolidge.

During an interview with Fitzhugh Green for Popular Science Monthly, Byrd explained his motivation for this initial Antarctic trip:

‘There lies down there at the bottom of the world a vast unknown region as big as the United States and Mexico combined that the eyes of man have never looked upon… And so it is that this ice-covered land is a great mystery and offers the last great challenge to the aviator and the explorer.’[2]

While attempting to win the 1927 Orteig Prize, Byrd and Bennet suffered a devastating crash that injured Byrd and seriously injured Bennet.

The nonstop flight from America to France was completed by Charles Lindbergh who went on to receive the coveted award. Undeterred by initial failure, Byrd reassembled his team to make the Atlantic crossing.

On July 1, 1927, Byrd, Acosta, Balchen and Noville flew from New York and crash landed that same day in France. The crash was without fatalities, and the crew were received, in France, as heroes.

On July 6, 1927, Prime Minister Raymond Poincare instated Byrd as an Officer of the French Legion of Honour. Upon return to New York Byrd and Noville were awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross by Secretary of the Navy, Curtis D. Wilbur.

Byrd famously stated that

“A static hero is a public liability. Progress grows out of motion”[3], and in 1928 Byrd set off on his first Antarctic expedition.

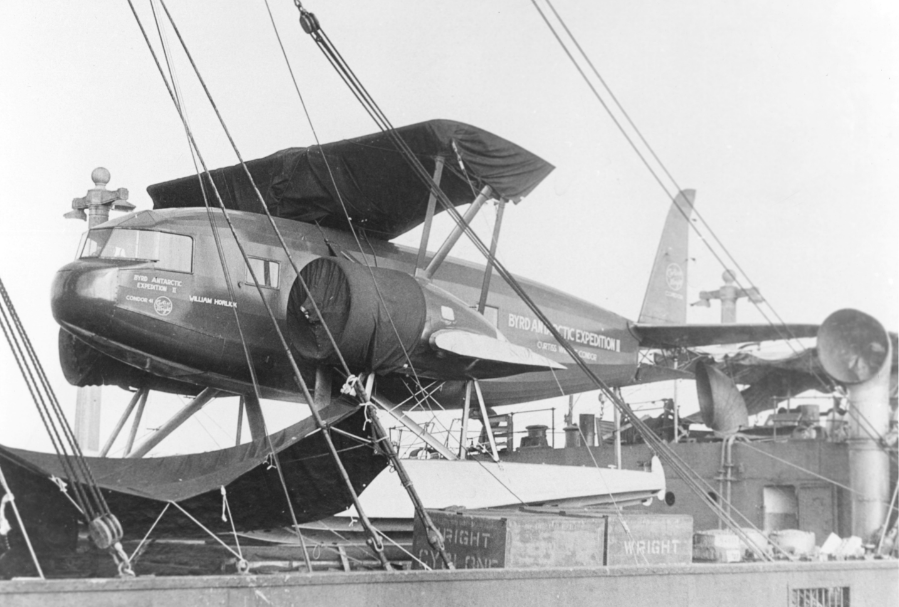

Drawn by the possibility of geological discovery, untapped natural resources and the development of new technology, he assembled two ships, three airplanes and a large team.

Admiral Richard Byrd’s flag ship, THE CITY OF NEW YORK leaving for Antarctica.

She was part of Byrd’s First Antarctic Expedition of 1928-1930. She was built in 1882, as a Norwegian sealer designed to withstand the pressures of polar ice (BSLOC_2018_2_34)

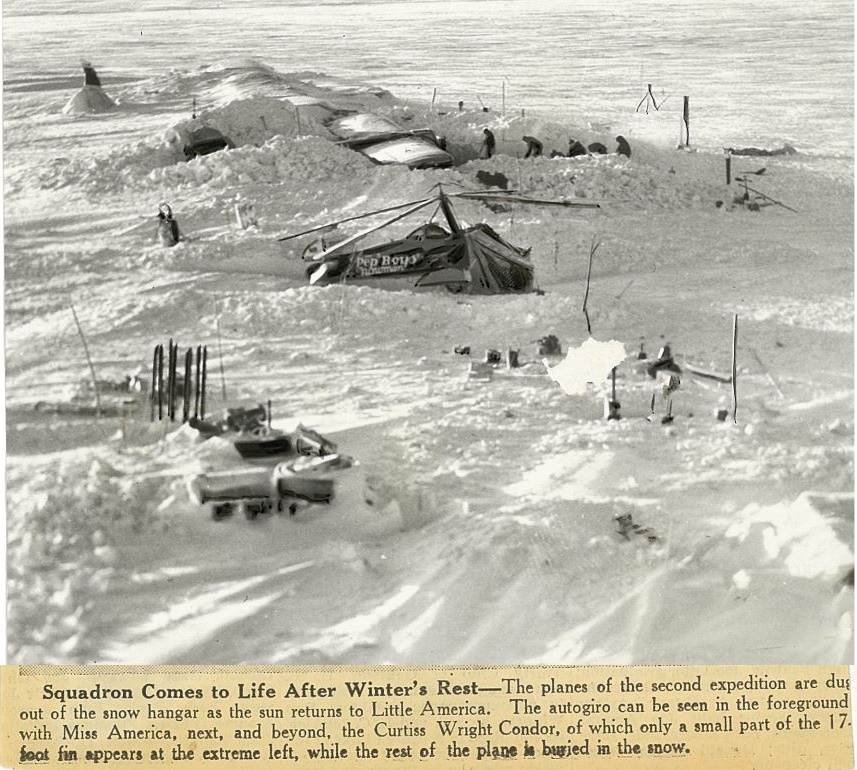

With the City of New York, a large Norwegian ship leading the way, there followed a Ford Trimotor named the Floyd Bennett, a Fairchild FC-2W2, NX8006 named Stars And Stripes and a Fokker Universal monoplane called the Virginia. The team set up base camp on the Ross Ice Shelf; affectionately naming their temporary home Little America.

Numerous geological investigations and photographic expeditions were carried out from Little America. Teams journeyed through the Antarctic’s treacherous conditions on dog-sled, airplane, snowshoe and snowmobile.

Throughout that summer radio communications continued with the outside world. The average American could tune in on a sweltering hot summers day to hear “As sun now gone 2 months, we are in complete darkness. Temperature at headquarters seventy-one degrees below zero. Wind ninety-four miles per hour. Drifting snow. All well. Byrd.”[4]

Having spent the winter months at base camp, expeditions were resumed on November 28,1929, with the first ever return flight to the South Pole. The Ford Trimotor had trouble gaining altitude forcing the crew to dump empty gas tanks and emergency supplies to reach the Polar Plateau.

This risky decision paid off, and Byrd, Bernt Balchen, Harold June and Ashley McKinley completed the journey in 18 hours and 41 minutes.

This ground breaking expedition was honored with the gold medal of the American Geographical Society.

Byrd became the youngest admiral in the history of the United States Navy after a special act of Congress promoted him to the rank of rear admiral on December 21, 1929.

The 1930 film, With Byrd at the South Pole, chronicled his adventures; capturing the imagination of a nation.

Byrd almost died on his second Antarctic expedition after spending five winter months alone manning a meteorological station. He was brought back to base camp after his team had received strange radio communications from Byrd.

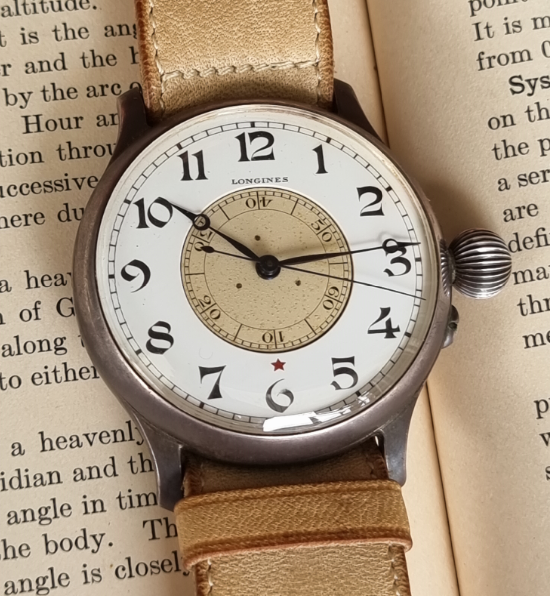

Longines archives confirm delivery of this 47mm Weems watch for Admiral Byrd’s second Antarctic expedition on the 29 August 1933. The expedition carried out extensive scientific test and Byrd made the most southerly radio broadcast ever made. He was holed up for 5 winter months alone in Bolling advance station, 100 miles further south of Little America. Longines archives note special adjustments to handle the extreme weather temperature and challenges of the expedition.

Upon arrival they found Byrd in poor mental and physical health, slowly dying from carbon monoxide poisoning. The rescue party returned Byrd to base camp, saving his life.

In the autobiography, Alone, he recalled his Antarctic solitude; that ‘Few men during their lifetime come anywhere near exhausting the resources dwelling within them. There are deep wells of strength that are never used.’[5]

Recalled on active duty in 1940, Byrd was forced to abandon his third polar expedition as his men continued on without him.

During WWII he was instrumental in national defense strategy, serving as an advisor to the United States Fleet and Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Ernest J. King. He headed a number of vital Pacific missions, visited the fighting front in Europe and was present at the Japanese surrender in Tokyo Bay on September 2, 1945.

Byrd went on to lead two further Antarctic expeditions backed by the US Navy. Code named Operation Highjump, Byrd’s fourth journey was to be the largest Antarctic operation to date.

With some thirteen US Navy support ships, six helicopters, six flying boats, two seaplane tenders and fifteen other aircraft; Operation Highjump was a colossal mission of gargantuan proportion.

Arriving on December 31, 1946, the crew immediately set to work. During the expedition aerial recordings of an area half the size of the United States were made, and ten new mountain ranges were discovered.

Byrd went on to command Operation Deep Freeze from 1955-1956. This was to be his final Antarctic trip and marked the beginning of a permanent U.S Military presence in Antarctica.

Bases were established at McMurdo Sound, the Bay of Whales and the South Pole. Byrd continuously maintained that discovery, and human advancement were paramount, hoping that ‘Antarctica in its symbolic robe of white will shine forth as a continent of peace as nations working together there in the cause of science set an example of international cooperation.’[6]

Before his death Byrd was the only individual to have received three ticker-tape parades.

He had amassed a number of awards and accolades including the Medal of Honor, the Silver Lifesaving Medal, the Navy Distinguished Service Medal, the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Navy Cross.

He was a daring man with an awe inspiring sense of adventure who spent his life striving forth into the unknown. He continually risked his own life for the continued development of mankind.

Footnotes

- Richard Evelyn Byrd, Longines Chronoscope (CBS: 1954, v.15) Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PrdSal9uH28 (Date Accessed: 09/08/16). ⏎

- Fitzhugh Green, ‘Dick Byrd – Adventurer’, Popular Science Monthly, (Vol. 113, No. 3, Bonnier Corporation, September 1928), pp 39. ⏎

- Charles John Vincent Murphy, Struggle: The Life and Exploits of Commander Richard E. Byrd, (Frederick A. Stokes, 1928), pp 325. ⏎

- Fitzhugh Green, ‘Dick Byrd – Adventurer’, Popular Science Monthly, (Vol. 113, No. 3, Bonnier Corporation, September 1928), pp 140. ⏎

- Richard Evelyn Byrd, Alone, (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1938), pp. 189. ⏎

- Richard Evelyn Byrd, Byrd Memorial at McMurdo Station, (Antarctica: Dedicated on 25 October 1965). Quoted from a statement made by Byrd during International Geophysical Year (IGY) operations in 1957. ⏎

Bibliography

Byrd, Richard Evelyn. Alone, (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1938), pp. 189.

Byrd, Richard Evelyn. Byrd Memorial at McMurdo Station, (Antarctica: Dedicated on 25 October 1965). Quoted from a statement made by Byrd during International Geophysical Year (IGY) operations in 1957.

Byrd, Richard Evelyn. Longines Chronoscope (CBS: 1954, v.15) Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PrdSal9uH28 (Date Accessed: 09/08/16).

Green, Fitzhugh. ‘Dick Byrd – Adventurer’, Popular Science Monthly, (Vol. 113, No. 3, Bonnier Corporation, September 1928), pp 39. Murphy, Charles John Vincent. Struggle: The Life and Exploits of Commander Richard E. Byrd, (Frederick A. Stokes, 1928), pp 325.