Byrd’s Longines Weems speaks of a time when explorers, aviators and aviatrix relied upon them as a robust tool watch essential for making navigational calculations. In early aviation and exploration this made the difference between success, failure, and at times, life itself.

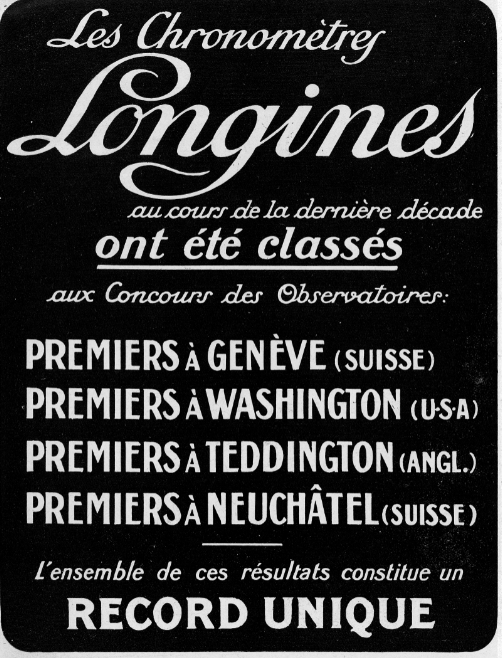

Over the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Longines won more precision timing and accuracy awards than any other maker from the four great observatories of the world – London’s Kew-Teddington, the US Naval in Washington and those in Neuchatel and Geneva.

Absent radio beacons, satellites and radar – an accurate, reliable timekeeper was relied upon for making navigational calculations, making the difference between life and death.

Lindbergh stressed, “Accuracy means something to me. It’s vital to my sense of values. I’ve learned not to trust people who are inaccurate. Every aviator knows that if mechanics are inaccurate, aircraft crash.

If pilots are inaccurate, they get lost-sometimes killed. In my profession, life itself, depends on accuracy”. The name Longines was second to none, for technical development, prowess, reliability and of course accuracy.

Aviation and exploration exploded in the early part of the twentieth century, and the extreme temperatures of the polar regions were brutal on both man and equipment. The intrepid explorer and adventurer, Prince Luigi Amedeo, the Duke of Abruzzi, used five Longines Chronometers aboard his ship Stella Polare, for his 1899 Arctic expedition that reached 86º 33’N, the most northern latitude ever reached at that time.

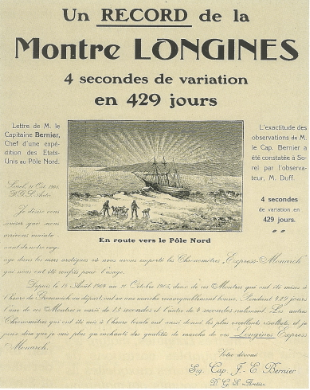

He noted their incredible reliability when he said, “they kept good time in spite of the sudden changes to temperature to which they were subjected” [1]. Canada’s most famous arctic explorer, Captain Joseph-Elzear Bernier, who was the youngest captain in Canada’s history, at just 17, also relied upon Longines chronometers for the extremes of polar timekeeping.

In 1909, he stated, “During 429 days in Arctic waters, our Longines watches performed perfectly. When a watch is taken from the pocket, it faces as much as 90 degrees change in temperature. This alone is sufficient to cause the average watch to go out of order. I cannot be too laudatory in my appreciation of the exceptional running qualities of your watches”. Over a one plus year duration, “one varied 13 seconds and the other only 4.”

The who’s who of early aviation and exploration history, including Admiral Byrd, relied upon Longines timepieces, aboard planes, ships and bathyscapes for record setting and exploration. Byrd was America’s greatest twentieth century explorer, receiving the Navy Cross, Distinguished Flying Cross, a Silver Life Saving Medal, and expedition medals for this three trips to Antarctica.

He was also awarded the Medal of Honor, America’s highest military award. Moreover, on December 21, 1929 at just 41 years of age, a special act of congress promoted Byrd, making him the youngest Admiral in the history of the United States Navy and this record remains to this day. His aviation and exploration exploits are unrivalled.

Longines chronometers timed the North west passage exploits of Roald Amundsen, along with almost all of aviation’s greatest feats and records.

Longines had a formidable team – the technical prowess of Alfred Pfister, along with one of aviation’s greatest gatekeepers, and visionaries, John P.V Heinmuller. Acquiring the nickname, ‘Aero One’, he departed St Imier in 1912, as a twenty-year-old, to join the clever entrepreneur Albert Wittnauer, the American Longines agent.

With the Great war on the horizon, the latter two were the key driving force behind the supply of cockpit instruments and plane calottes to the burgeoning U.S. Army Air Corps and other military forces. The French air force took delivery of calottes as early as 1915, with advertisements appearing in the French title L’Illustration by 1916.

Heinmuller served as Vice President of Wittnauer from 1921, and later the President in 1936 of the Longines-Wittnauer Company. He was the chief official timer for the National Aeronautic Association, the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale and presided over the World Air Sport Federation. He was a personal friend to many of aviation’s greatest names, recorded and ensured recognition for many of these early aviation exploits in his book, Man’s Fight to Fly.

Admiral Byrd often wore his famed Longines pusher-in-crown, 13.33 chrono, and appeared in magazine ads wearing this piece. Longines role developing chronometers, specialist aviation instruments and timepieces in the first half of the twentieth century for the age of exploration and aviation was unrivalled. They were without question the pre-eminent supplier of watches to Byrd.

Records indicate his receipt of a 1920 chronometer using caliber 21.29, with serial number 2811799, and his receipt of chronometers, and aircraft calottes for his 1926 Arctic expedition, and a year later attempting to claim the Orteig prize by crossing the Atlantic first.

Longines timepieces also accompanied him on his first three Antarctic missions in 1929, 1934 and 1939 along with a pair of (most likely) modified Waltham Vanguard pocketwatches received from Weems.

Byrd famously stated that “A static hero is a public liability. Progress grows out of motion”[2], and in 1928 Byrd set off on his first Antarctic expedition. Drawn by the possibility of geological discovery, untapped natural resources and the development of new technology he assembled two ships, three airplanes and a large team.

With the City of New York, a large Norwegian ship leading the way, there followed a Ford Trimotor named the Floyd Bennett, a Fairchild FC-2W2, NX8006 named Stars And Stripes and a Fokker Universal monoplane called the Virginia. The team set up base camp on the Ross Ice Shelf; affectionately naming their temporary home Little America.

Numerous geological investigations and photographic expeditions were carried out from Little America. Teams journeyed through the Antarctic’s treacherous conditions on dog-sled, airplane, snowshoe and snowmobile. Throughout that summer radio communications continued with the outside world. The average American could tune in on a sweltering hot summers day to hear “As sun now gone 2 months, we are in complete darkness. Temperature at headquarters seventy-one degrees below zero. Wind ninety-four miles per hour. Drifting snow. All well. Byrd.”[3]

Having spent the winter months at base camp, expeditions were resumed on November 28th, 1929, with the first ever return flight to the South Pole. The Ford Tri-motor had trouble gaining altitude forcing the crew to dump empty gas tanks and emergency supplies to reach the Polar Plateau. This risky decision paid off, and Byrd, Bernt Balchen, Harold June and Ashley McKinley completed the journey in 18 hours and 41 minutes.

This ground breaking expedition was honoured with the gold medal of the American Geographical Society. Byrd became the youngest admiral in the history of the United States Navy after a special act of Congress promoted him to the rank of Rear Admiral on December 21, 1929. The 1930 film, With Byrd at the South Pole, chronicled his adventures; capturing the imagination of a nation.

Longines chronometers along with most likely modified Waltham Vanguard Second-setting pocket watches likely accompanied him on his first Antarctic mission in 1928. This expedition, predated the very birth of the Longines Weems aviator’s wristwatch.

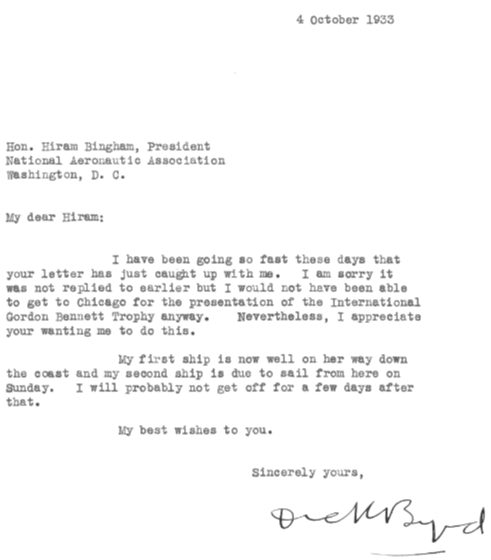

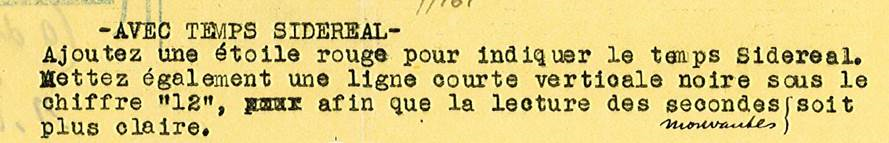

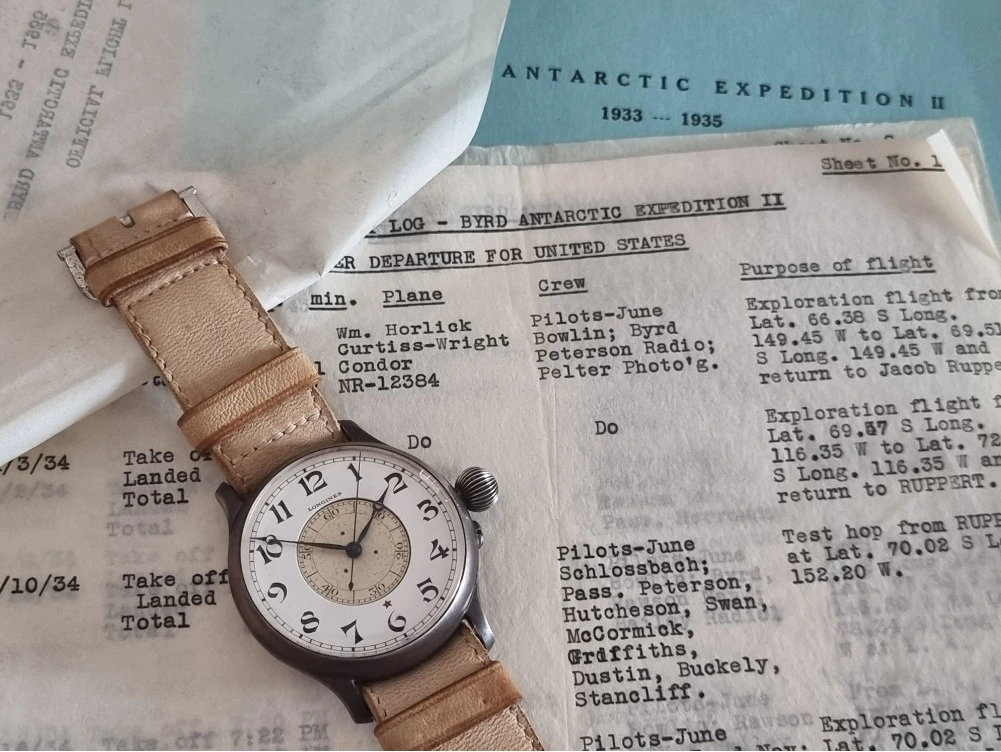

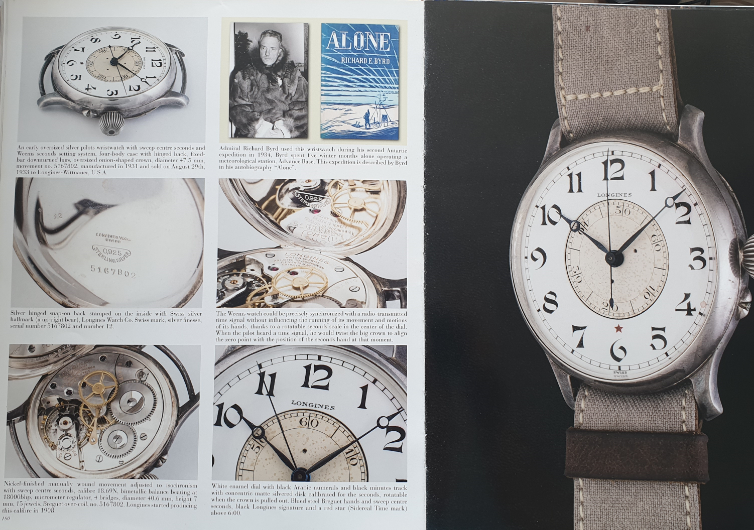

However, for his Second Antarctic Expedition archives note 1933 communication with Byrd, and the order of a very special silver cased Weems wristwatch piece with serial number 5167802 being delivered to him on August 29, 1933.

The watch used an “extra quality” nickel silver calibre 18.69N, adjusted for isochronism, and sidereal time, with notations on the movement and recorded in the archives. The dial featured a single red star at six on the dial which Longines first used in October 1932, to note regulation to star or sidereal time. Celestial navigation was critical to Byrd at the Poles as a compass cannot function.

Wiley Post and Harold Gatty used a Weems pair adjusted in this manner, creating history with their record breaking round the world flight in 8 days, 15 hours, and 51 minutes in June 1931. Longines archives note use of the star on the dial for indicating sidereal time on October 25, 1932. Longines were the first to make wristwatches regulated for sidereal time, and Byrd’s Weems was one of the very first made.

Weems pieces adjusted for sidereal time came with the following dial configurations – a normal dial, a single red star at six, sidereal time text only, or one marked sidereal time plus two red stars at three and nine in either the 18.69 or 37.9 caliber.

There is a small vintage photo of Byrd at Rapa Nui (Easter Island) where they stopped on the way down to Antarctica with Byrd pictured wearing his Weems. A periscope film of the adventure on Rapa Nui also captures this.

Original typescript flight logs for this second Antarctica expedition 1933-1935 record a total of 169 hours of navigational, mapping, exploratory, photographic, seismological, meteorological, and equipment testing flights undertaken by Byrd and team members with the four planes on the mission.

Flights even included a parachute jump. On the mission, Byrd made the most southerly radio broadcast ever made and carried out an extensive range of biological and scientific experiments.

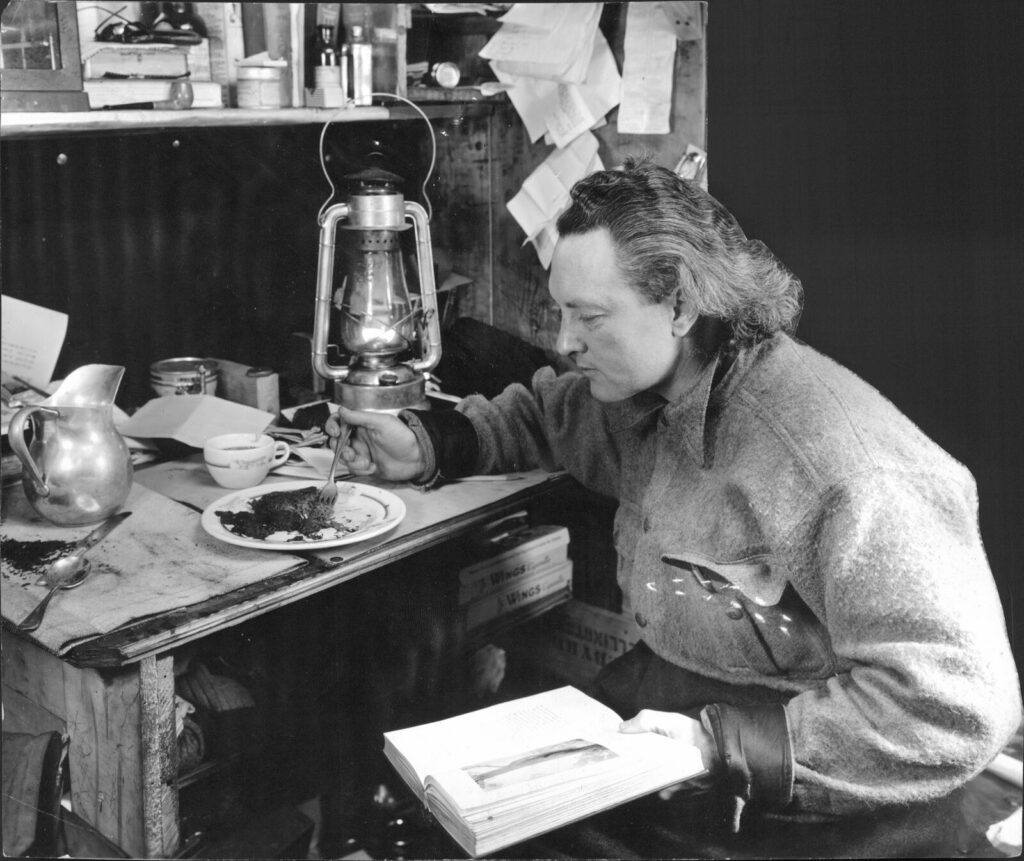

Byrd was later trapped at Bolling Advance Station 123 miles south of Little America, and barely survived after spending five winter months in complete isolation alone manning a meteorological station. After receiving strange radio communications, a complex recovery operation was initiated and crew members managed to reach him.

Upon arrival, they found Byrd in poor mental and physical health, slowly dying from carbon monoxide poisoning. The rescue party returned Byrd to base camp, saving his life. In the autobiography, Alone, he recalls his Antarctic solitude; that ‘Few men during their lifetime come anywhere near exhausting the resources dwelling within them. There are deep wells of strength that are never used.’[4]

Nothing can overstate the significance that Byrd and the other men and women of aviation played during this golden age of aviation and exploration. Failure, heroism, bravado, and the progression of air navigation – establishing one’s position in the air, shaped and contributed to the pen-ultimate success of aviation.

Originally two basic methods of early navigation existed. The first – ‘pilotage’, where known landmarks, rivers, mountains, and maps were used to assist at lower altitudes. The other, ‘dead reckoning’, included taking the last definitely known position and carrying forward with the last known speed, drift, course, and use of a compass. To this, radio and celestial navigation were added.

The window for these specialist avigation timepieces was very short with ever changing military technology expanding radar and satellite use. Further, engine reliability and performance dramatically improved and positively changed aviation safety.

Byrd’s Antarctic Expedition Longines Weems, and an expedition’s needs for other specialist timepieces, chronometers and instruments in the extreme regions of this world cannot be overstated. Some have survived and speak of a truly different time.

Many of aviation’s early pioneer’s lives were cut drastically short due to a navigational miscalculation, timing, equipment, or mechanical failures.

Footnotes

- Wittnauer – a history of the Man & his Legacy

- Charles John Vincent Murphy, Struggle: The Life and Exploits of Commander Richard E. Byrd, (Frederick A. Stokes, 1928), pp 325.

- Fitzhugh Green, ‘Dick Byrd – Adventurer’, Popular Science Monthly, (Vol. 113, No. 3, Bonnier Corporation, September 1928), pp 140.

- Richard Evelyn Byrd, Alone, (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1938), pp. 189.

Thanks for filling in some family history.

A relative of mine, “Pete” Demas, was one of the four men that rescued Byrd for the South Pole station. I still have an Easter Island “Kava-kava” statue that Uncle Pete picked up on the stopover you mention.

I guess I have to start looking for a Weems!

Thanks,

Dr. George N. Demas

Dr Demas… a very big thank you for the feedback. I have a mission book summary with correspondence and letters from Dr Poulter who was second in charge and I believe in charge of rescue attempt. I will have a look through that.. perhaps you can email me at andy@flightbirds.net and I will see what I can find something that may help colour Uncle Pete for you. Andy 😉

I’m a Weems! He was my great grandfather. I have so many of his things!

Alison

Greetings Alison and many thanks for your response and feedback. I have a wonderful document that may help colour part of the rescue attempt of Byrd by your relative and would be delighted to provide it to you. It describes the rescue mission in great detail. I would also love to hear what you may have in the way of supporting information and can be reached at info@flightbirds.net or andy_timeman@yahoo.com. Andy;)

Greetings Alison… you are very lucky to have such a remarkable grandfather. I have possibly previously responded when asleep. I have great interest in passion in all of your grandfather’s remarkable achievements in navigation and beyond. Without doubt he played an essential role in helping shape aviation navigation history and with it the world we know today. My passion in collecting the watches your grandfather was responsible for bringing to life has been over the last 35 years. On Sunday morning, I am again reading letters from him to John Heinmuller and Lindbergh. Perhaps there is a watch or two that someone in the family may have that you might allow me to write about. Andy 🙂