John P.V. Heinmuller recalls in his book that ‘The hearts of all civilization beat faster for Lindbergh during those trying 33 hours and 39 minutes, and there were many who felt that his solo, nonstop attempt was doomed to failure.’[1]

Within a year of claiming the Orteig prize, a quarter of the American population, some 30 million, visited Lindbergh and the Spirit of St Louis. Throughout 1927, public interest in aviation soared, with applications for pilot’s licenses tripling, licensed aircraft quadrupled and commercial airline passengers grew from 5,782 to 173,405 between 1926 and 1929.

Lindbergh’s flight “marked the breakout year of commercial aviation in the United States [and] the beginning of what came to be called the Lindbergh boom.”[2]

The Spirit of St Louis visited 82 cities in all 48 states, with Lindbergh delivering 147 speeches and appearing in countless parades. The 22,350 mile tour saw an American public obsessed with the pilot and everyone wanted to fly. Distinguished aviator, Elinor Smith Sullivan, later recalls this period:

people seemed to think we [aviators] were from outer space or something. But after Charles Lindbergh’s flight, we could do no wrong. It’s hard to describe the impact Lindbergh had on people. Even the first walk on the moon doesn’t come close. The twenties were such an innocent time, and people were still so religious—I think they felt like this man was sent by God to do this. And it changed aviation forever because all of a sudden the Wall Streeters were banging on doors looking for airplanes to invest in. We’d been standing on our heads trying to get them to notice us but after Lindbergh, suddenly everyone wanted to fly, and there weren’t enough planes to carry them.[3]

In 1927, at just 25 years of age he became Time magazine’s very first “Man of the Year”. His name was synonymous with aviation throughout the Western World as every major newspaper, magazine, and radio station in the U.S. jostled to interview him. For the American population Lindbergh had achieved the impossible, inspiring them to reach for the skies both commercially and personally.

He was the most marketable commodity in the world. All brands including American watch makers – Helbros, Bulova and others clambered for his endorsement. Whilst little is known of the watch that may have accompanied him on the crossing, it is known he owned two Weems Second-setting watches following.

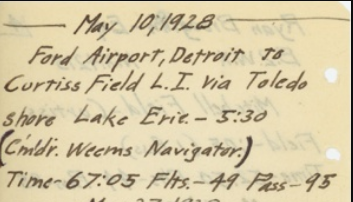

After getting totally ‘lost’ in 1928 whilst flying over Florida waters, he decided to expand his avigation training with the grandmaster PV.H Weems. Flight logs of Lindbergh for May 10, 1928 record C’mdr Weems serving as the navigator on board.

His very first Weems was a modified Waltham Vanguard pre-Longines ‘Weems’ and he also took delivery of a Longines Lucy ‘Hour-angle’ prototype model in the mid 1930’s. The first would play a part in shaping the famous Longines version delivered in November 1928 and the latter played an essential role shaping one of the most famous watches in aviation history, the large Hour-angle.

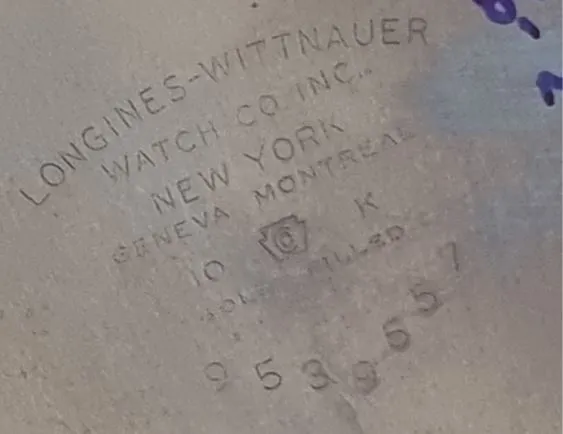

The large Hour-angle received Swiss patent approval on October 1, 1931 from the International Office of Industrial Property of Berne with the first known deliveries in November. The Great Depression caused a wholesale collapse in almost all industries, businesses and finance including aviation, and Longines were not spared. Wittnauer sales of Longines watches collapsed to their lowest point since the formation of A.Wittnauer Company in 1890.

The malaise lasted for much of the 1930’s and whilst some economic prospects were changing Weems US Patent 2008734 for an apparatus for a navigator’s timekeeping was approved on July 23, 1935 after a six year wait. In 1936, the Longines-Wittnauer Company was formed after Martha Wittnauer who had been on the verge of bankruptcy sold out.

John Heinmuller became President of the new entity and later that year the New second-setting watch would be born. Weems had a relationship with the UK agent Baume, and in September 1936, Baume submitted a list of technical improvements noted by Weems to Longines.

Their reply noted, “What he is suggesting has already been accomplished in a slightly different manner. Instead of the break lever working on the lug, which seems very practical, we have designed for stoppage to be enacted via a small additional crown at 4 o’clock, but which could also be placed elsewhere, at 2 o’clock, or on the other side of the lugs at 8,9 or 10 o’clock”. [4]

The first nickel silver prototype sample of the New second-setting watch with a turning bezel to make the adjustment was sent to Baume the London agent for Weems to inspect and horology history was made once again.

The first two Weems models to arrive in the 33mm case were ref 3930 and 3931 with the latter having a thumb lock. It is suspected that some of the very first examples of this of New second –setting watches were those first supplied to the U.S. Naval Academy in August 1937.

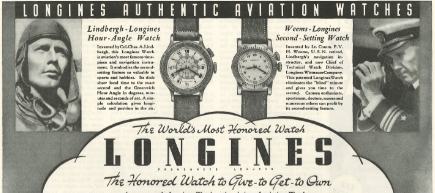

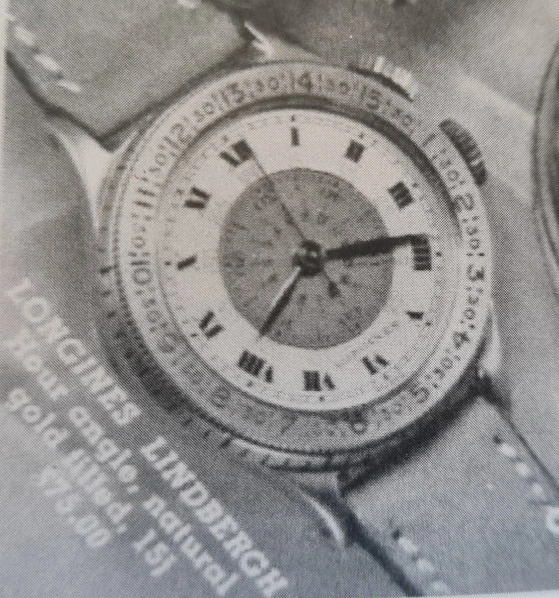

A few models were developed and took shape in the first six months of 1937 including a smaller 28mm Weems model and the first small Lindbergh Hour-angle. A magazine sales ad of November 1937 has pictures of both the 28mm Weems and small Hour-angle watches.

The small model Lindbergh was also purposed as a navigation instrument and likely intended for daily use.

The ‘Lindbergh Boom’ had dramatically expanded the number of pilot licences, aviatrix and commercial passengers as effects of the Great Depression waned.

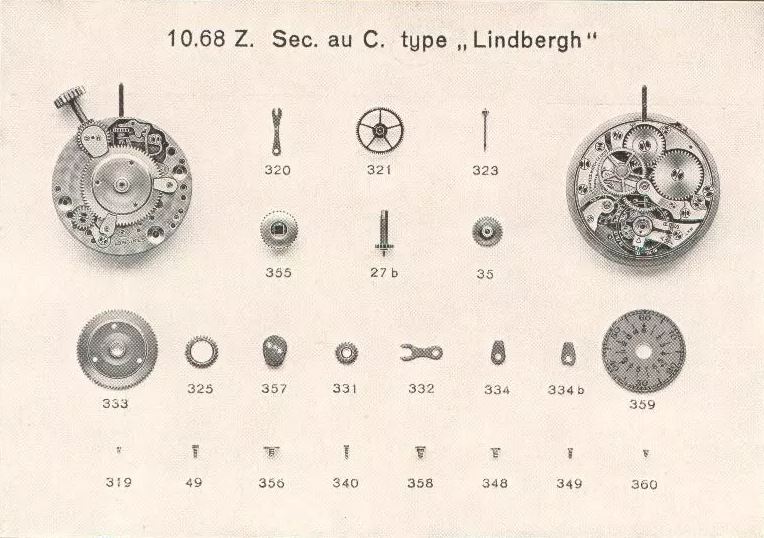

The watch used a number of calibres

- 10.68N (1939) or Z (first developed 1932)

- 11.68N or Z

- 12.68N (1939) or Z (first developed 1929)

Watches of the 1930’s were considerably smaller than the norm of today and it is difficult to envision the functionality of the smaller size as a serious tool watch when compared with the larger Hour-angle version. Both Hour-angle pieces were considerably larger than the 28mm Longines sterile dial Weems (A-11) issued to the US military in 1940.

There were a total of four versions of the Lindbergh Hour-angle watch in 33mm. Three in steel and one goldfill model. The steel models came either with or without the thumb lock device and were supplied as a complete watch from St Imier.

The silver bezel featured two colour enamel calibration markings (black and either green or blue) and blued steel feuille hands.

Goldfill versions 32mm in size used local cases and bezels made by Keystone Watch Case Company in Riverside N.J., with Longines supplying movements and dials.

The same local case maker was also used for the small 28mm Weems models in all case configurations, chrome, goldfill or 14k gold.

The first backs on these first small steel Hour-angle pieces was marked

Longines Lindbergh Hour-angle watch

Invented by Col. Chas. A. Lindbergh

US Pat Nos 1923305

Almost all were sold in the American market and featured the US patent text on the back. Research is ongoing and the author has yet to see an advertisement from any other country featuring the watch and whilst watches will have been delivered internationally the author is only aware of a single example delivered outside America.

This watch, a steel piece with serial number 7930836 was delivered to the Uruguay agent, Danero Y Pisano, on October 10, 1951. The watch case has no patent text on the back, has full moon breguet type hands and uses what must be the very last of the calibres used in this model 12.68N.

Lindbergh the ‘Lone Eagle’ was the most marketable commodity in the world in the late post 1927 and through much the thirties. In the 1930’s he was actively involved and appointed to senior government committees on aerospace development, securing funding from Guggenheim to support Goddard’s rocket development in Roswell.

The revival of Longines-Wittnauer Co in 1936 and the ‘World’s Most Honored Watch’ slogan was a huge positive for Longines sales, but the small Hour-angle watch bearing Lindbergh’s name would arrive at a very complex juncture. It arrived late 1937 and had a very challenging sales window ahead for a number of reasons.

Whilst the economy had improved from the worst of the Great Depression, the Lindbergh’s had been out of the limelight for three years following the kidnapping of their child in 1932. Both sizes of the famous Hour-angle watch in America would be greatly challenged post 1938 by the extensive relationship Lindbergh developed with Germany prior to the outbreak of WWII as the world prepared for war.

At the behest of the U.S. military attache in Berlin, Lindbergh visited Germany six times between 1936 and 1938 receiving unprecedented access to Luftwaffe facilities and was asked to report on German planes, pilots and flying technology. Lindbergh was to inspect all of the German planes to be used in the ever looming war.

Lindbergh greatly admired German engineering and was impressed with the developments they had made. He spoke of the strength and skill of the Luftwaffe who had created powerful planes “which combines [the] simplicity of construction with such excellent performance characteristics.”[5] He was even allowed to fly the Ju 88 bomber and Bf 109 fighter.

He received the Commander Cross of the Order of the German Eagle medal awarded by Göring on October 18, 1938.

A decoration that Lindbergh’s wife Anne presciently called “The Albatross.” As atrocities committed by the Nazi party came to light Lindbergh sparked controversy by refusing to give the honour back tainting his reputation forever.

Lindbergh, in a rather level headed manner remarked, ‘It seems to me that the returning of decorations, which were given in times of peace and as a gesture of friendship, can have no constructive effect. If I were to return the German medal, it seems to me that it would be an unnecessary insult. Even if war develops between us, I can see no gain in indulging in a spitting contest before that war begins.’[6]

Throughout the Second World War, Lindbergh strongly advised against American involvement. This was a very controversial view with many Americans branding Lindbergh a Nazi sympathiser. His reputation amongst the American public never fully recovered after WWII. In 1940, he became the spokesman for America First.

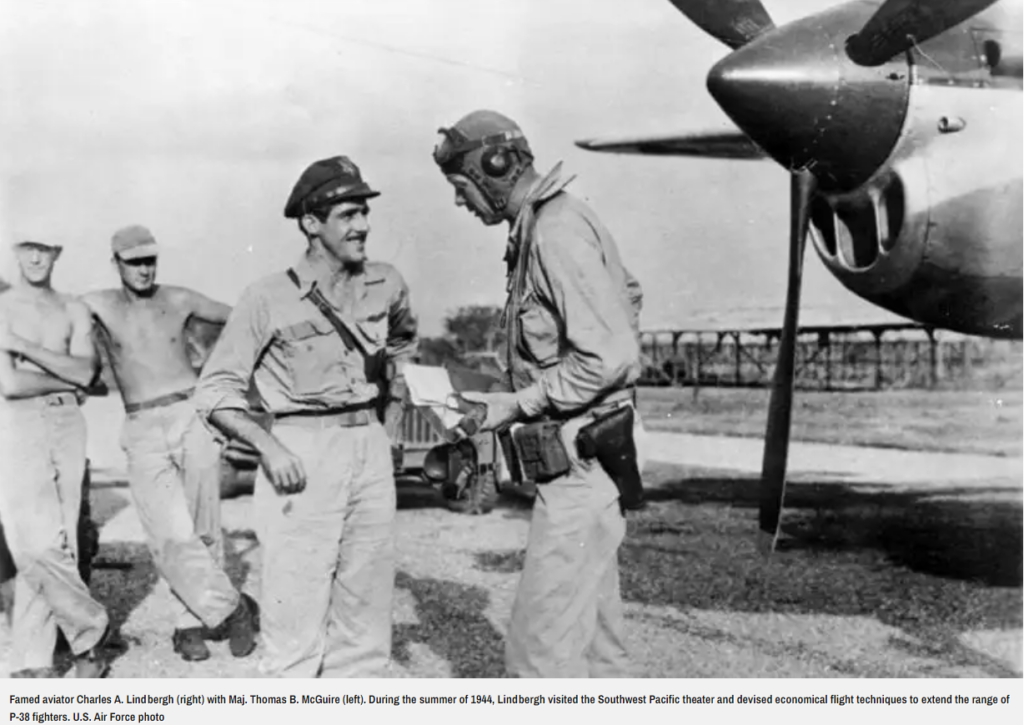

He urged America not to enter the war and argued in favour of upholding the Monroe Doctrine. Again, this was met with outrage by many. President Roosevelt publicly shamed his views and, in 1941, Lindbergh resigned as a colonel from the United States Army Air Forces. Whilst he later served in USAF in the Philippine theatre of war in 1944 he had been tarred for life.

Aside from these issues in the leadup to WWII, significant advancements were made with military technology, radar and radio communication’s air highways greatly reduced the need for specialist navigation skills and watches like the Hour-angle.

Therefore, given the date of its market arrival and lack of advertising, it is apparent why the sales window closed quickly and why there were a number of serious impediments to sales of the small Hour-angle model.

One of the reasons why catching a good example of a small (or large) Longines Hour-angle watch, a rare breed in the wild, is sort of like finding a winning lotto ticket.

[1] John P.V. Heinmuller, ‘IV Charles Augustus Lindbergh,’ Man’s Fight to Fly, (New York: Aero Print Company, 1945), pp. 68.

[2] A. Scott Berg, Lindbergh, (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1998), as cited in Belfiore (2007), pp. 17.

[3] Peter Jennings and Todd Brewster, The Century, (New York: Doubleday, 1998), pp. 420.

[4] Longines through Time The story of the Watch Stephanie Lachat p116

[5] Stewart Halsey Ross, How Roosevelt Failed America in World War II, (McFarland & Company, Inc.: Jefferson, North Carolina and London, 2006), pp. 44.

[6] Stewart Halsey Ross, How Roosevelt Failed America in World War II, (McFarland & Company, Inc.: Jefferson, North Carolina and London, 2006), pp. 44.