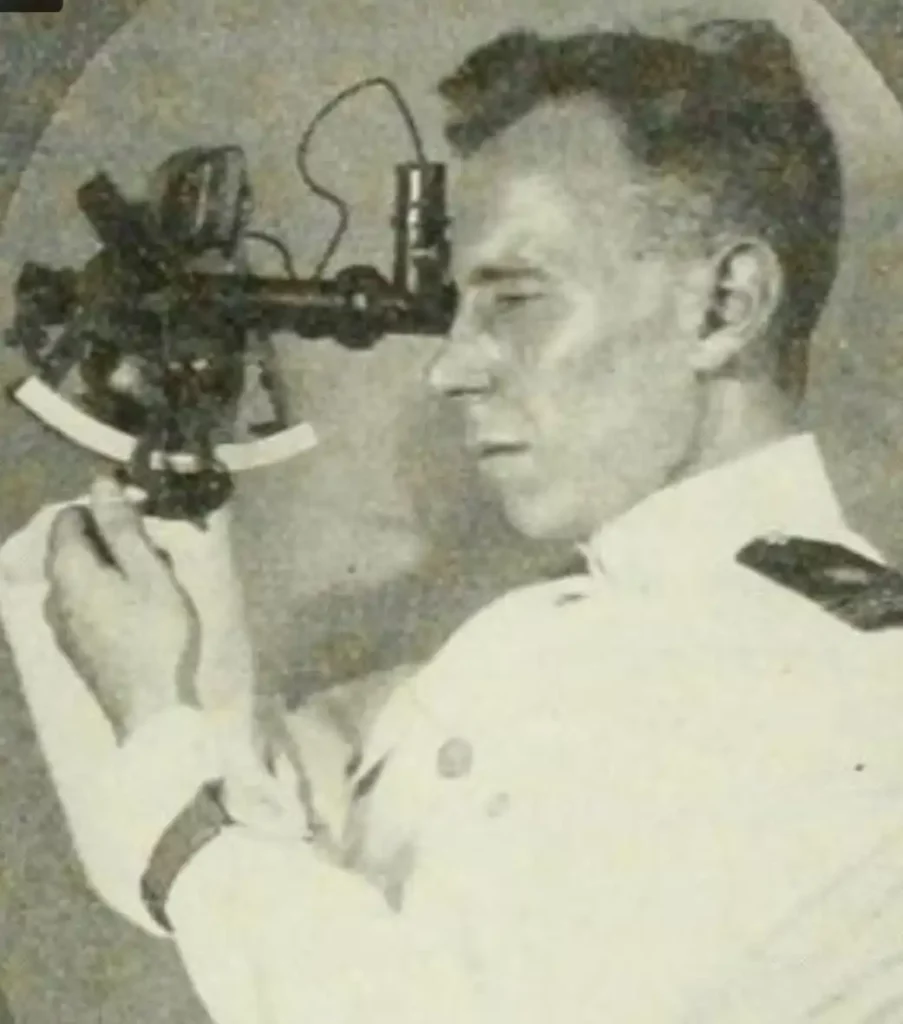

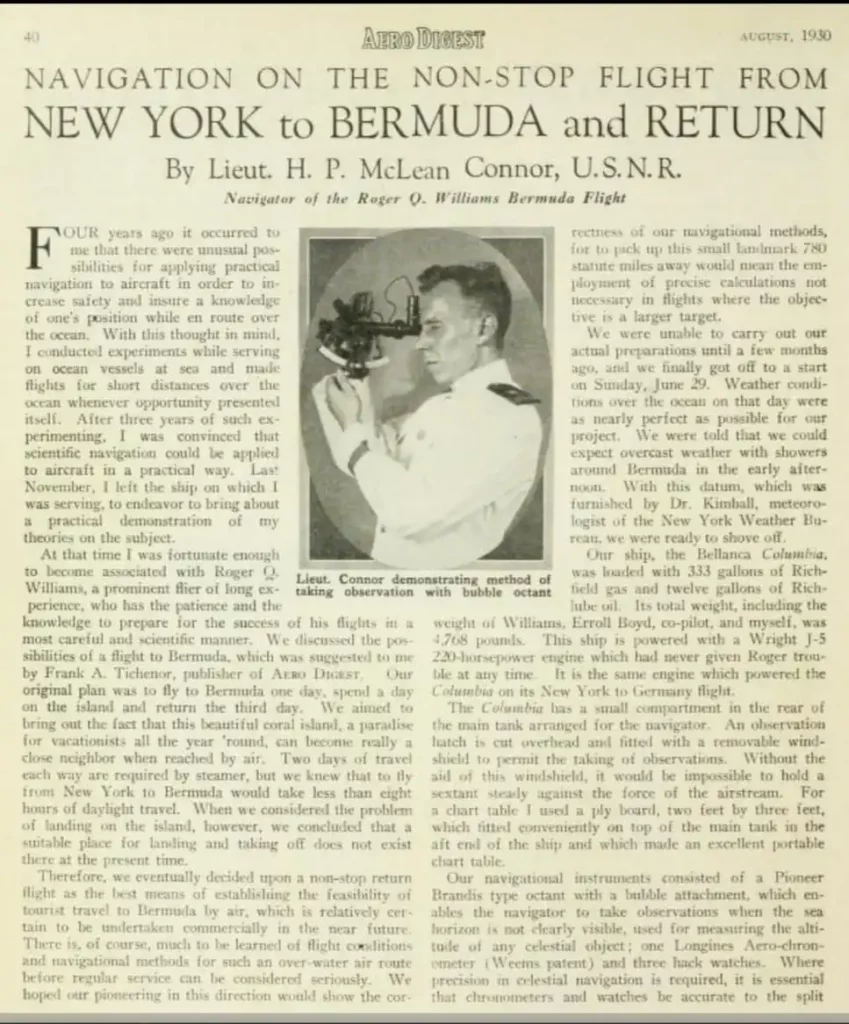

Today’s Instagram wrist shot era may well have been started by a legendary navigating star -Lt. Harry P. McLean Connor. How so? The master navigator and pilot gave us one of our very first wrist shots and watch reviews 93 plus years ago in the August 1930 edition of Aero Digest.

This followed his navigating role during a record-breaking non-stop return New York to Bermuda flight made in the famous “Columbia”, a Wright Aviation, Guiseppe Bellanca designed plane, that was already famous in its own right.

The renamed plane would serve Lt. Connor well and his navigational role with famed aviators Roger Q Williams and Canadian Errol Boyd in June 1930 was made without radio equipment to prove that navigation by dead reckoning and celestial observations could be successfully applied in a practical way. They aimed to test instruments and navigational skills for future commercial flight opportunities between the two destinations that would not follow till seven years later.

Initially, the flight was planned as a one-way trip with them expecting to land in Bermuda and return the following day. Pundits were giving 5-1 for their early departure. Their plane, Columbia, flew without pontoons, experienced appalling weather conditions, suffered equipment failure, and at one stage the only viable option considered was a crash landing. However, upon sighting the islands, ‘Boyd noted that…Connor had a grin from ear to ear. This slim calculating naval officer had accomplished a navigational feat second to none.’ [1]

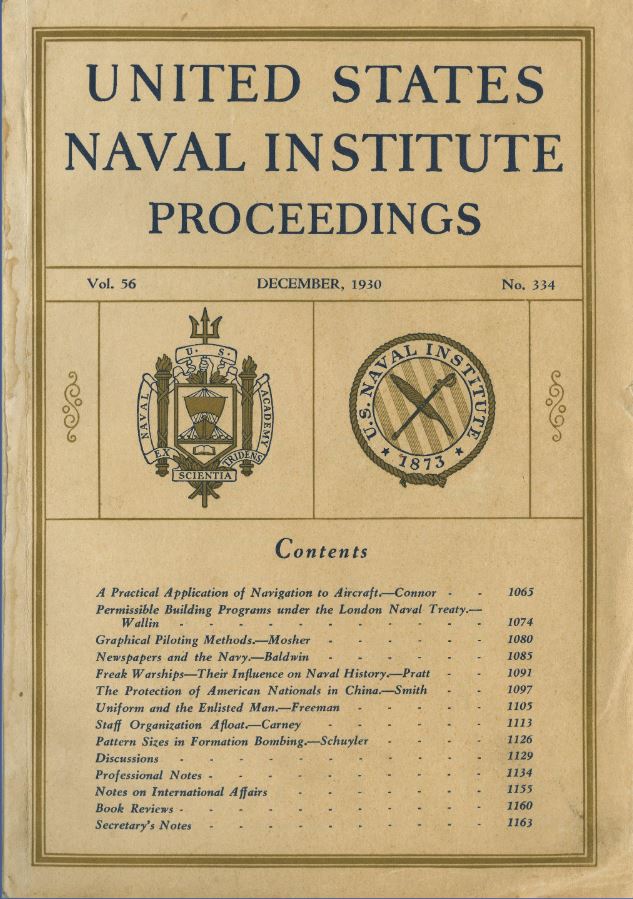

A detailed account of the flight was published in a December 1930 USNA publication with the article titled, Use of Scientific Navigation to Aircraft for Transoceanic Flying.

Lt. Connor noted that for ocean flying a thorough knowledge of meteorology and seamanship was necessary and this could only be obtained from years of experience at sea.

His suggestion was that only navigators who have had a number of years’ service as line officers in the Navy or Merchant Marine be permitted to act in such capacity.

Incredibly, he noted that contemplated ocean flights should have government supervision of some kind to enhance their success and the use of radio for transoceanic flying.

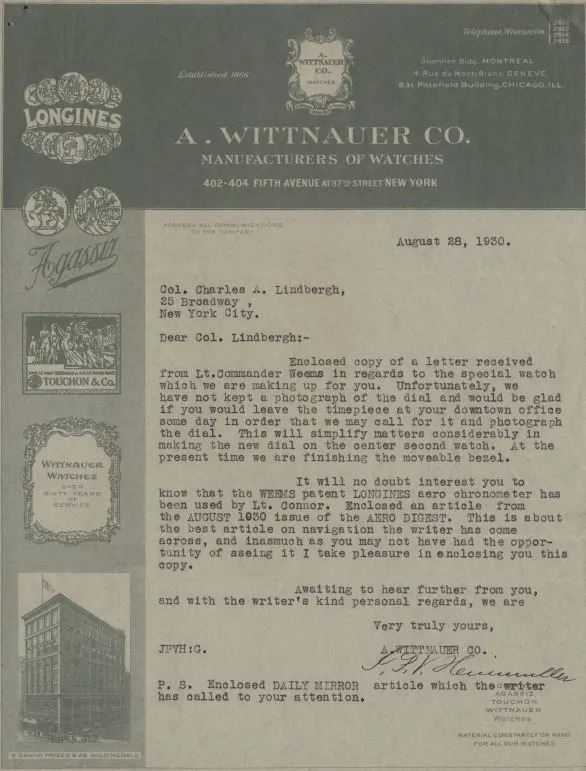

Lt. Connor’s 1930 review in Aero Digest was the very first known to use and sing the praises of the Longines ‘Aerochronometer’ Weems Second-setting watch. Harry’s watch was part of order #1395, the very first made by Wittnauer, the US agent for Longines, in 1929.

Initially placed before the start of the great depression, delivery was made April 10th and May 2nd 1930.

In the article, Lt. Connor is pictured wearing his oversized Longines Weems wristwatch and notes using it along with three Longines hacking watches on their New York to Bermuda flight.

The term ‘Aerochronometer’ was borrowed from an instrument designed and developed by Harold Gatty. Known as the “Prince of Navigators”, he ran Weems navigational training academy in San Diego and with Wiley post made an incredible record breaking eight day Round the world flight in 1931.

Seemingly, the wrist shot era started, without so much as a credit going to Lt. Connor.

An early 1930 Longines ad by Wittnauer detailing their role as the Aviator’s watch and their incredible flight success noted,

“Navigation an easy task with Longines timepieces”

“Your Longines Aerochronometers and watches rendered us inestimable assistance enabling us to keep the Columbia on direct course throughout (the) trip and to hit Bermuda on the nose. Where minute precision in celestial navigation is required it is essential that chronometers be accurate to split second.”[2]

The Guiseppe Bellanca designed plane was originally named Miss Columbia, after the owner, Charles Levine’s daughter and was already famous in its own right. Between April 12 and 14, 1927 pilots Clarence Chamberlin and Bert Acosta set an endurance record of 51 hours, 11 minutes and 20 seconds above the Roosevelt Field.

An injunction taken out by the co-pilot stopped Miss Columbia from flying and aided Lindbergh claiming the Orteig prize. Just two weeks later it made an attempt at flying from New York to Berlin falling just short. The owner, Levine who stiffed the co-pilot claimed to be the first passenger to cross the Atlantic.

It was now Boyd and Connor’s turn. Fresh from their successful Bermuda June 1930 flight, Boyd planned an Atlantic crossing with the Columbia.

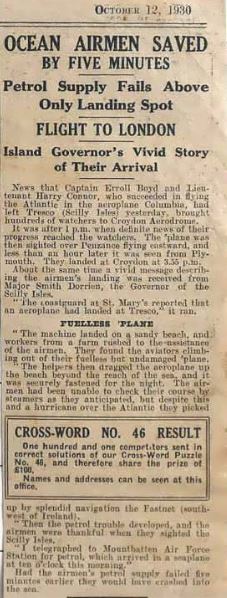

The plane, renamed the Maple Leaf, was the chosen workhorse companion for Errol Boyd and Lt Connor’s planned October 1930 Trans-Atlantic crossing – a world first, outside summer months.

A series of mishaps did not stop the flyer’s success. Vibrations on takeoff rendered the earth-inductor compass dial unserviceable, forcing the pair to rely on two magnetic compasses.

Moreover, an hour after dark, they experienced an electrical failure and had to use the emergency flashlight to energize the phosphoric material on the instrument panel with Boyd later noting, ‘Boy, it was dark! I felt as though I was piloting a car in a coal mine.’ [3]

A fuel blockage forced them to dump 100 gallons of fuel to avoid a fire on landing and even that event did not end their voyage.

The pair managed to make a miraculous landing on a narrow six-metre-wide beach strip in the Scilly Isles, 30 odd miles south-west of Cornwall. With the help of locals, they flew onto Croydon airport the next day.

Once again, Lt Connor, would establish his worth as a navigating legend and was a scientific fanatic in all firms of navigation. Harry’s pre Instagram skills were on display once again with his chosen Longines Weems second-setting wrist companion pictured on his wrist at Harbour Grace, in Newfoundland, and on arrival at England’s Croydon airport.

In an interview in the company of Moore-Brabazon, the first Englishman to fly a plane, a pragmatic Lt Connor noted to the interviewer that their Atlantic crossing was a test for the instruments and nothing more and that any catastrophe leading to death would imply nothing more than a failure of the equipment. His Longines Weems was one of his navigational trump cards that delivered success.

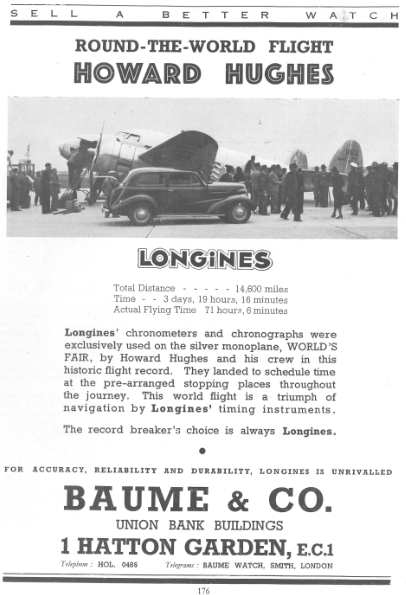

Harry’s navigational pursuits continued, and he was later recommended by Harold Gatty, the man Lindbergh described as the Prince of Navigators, to join Howard Hughes as a pilot and navigator aboard his record breaking 1938 Round the world flight in a modified Lockheed Super Electra 14-N2. The plane was offered free of charge to Hughes because of the publicity it would generate. The voyage set off from Brooklyn’s Floyd Bennett Field in July 1938, flying some 23800km with a flight time of 71hours at an average speed of 206 miles per hour. It bettered Wiley Post’s incredible July 1933 solo flight time by an incredible three days, twenty three hours, and thirty three minutes.

It is important to note that whilst Howard Hughes and Wiley Post’s flights were marketed as round the world that both circled the northern hemisphere, they were 12,968 kilometres short of a true RTW as recognized by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. To qualify with the FAI, there is a requirement of the circumnavigation crossing all meridians in one direction and be at least the length of the Tropic of Cancer, some 36,788km.

Such were the dangers of early aviation pursuits, that the Hughes’s Super Electra plane used on the successful flight was sold onto the Royal Canadian Air Force. Less than two years later in November 1940, the plane on a fight from South Africa to Egypt banked to the left, stalled on takeoff and entered a spin before crashing and killing all.

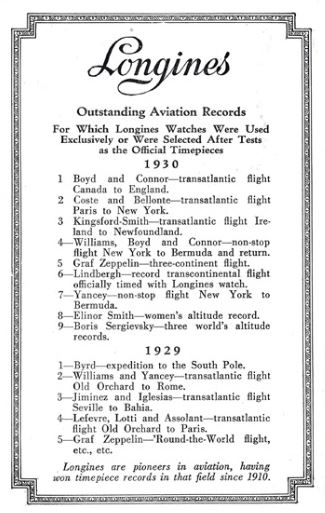

Whilst aviation’s interwar golden years have a romantic attachment to this incredible transformational chapter, they were extremely dangerous and many a pilot paid the ultimate price. One incredible reminder of these Golden years of aviation is a Longines salesman’s display board that serves as an incredible reminder of just how much the St Imier maker ruled the skies and the land below.

One third of the names on the salesman’s display board tragically lost their lives pursuing records and advancing aviation. Longines enjoyed a remarkable multi-decade zenith at the forefront of precision timing. Their technical department were the world leader in precision timing with technological advancements that enabled delivery of the most famous and important chronographs, and specialist instruments for those who wrote and broke aviation’s record books.

The household names of the display board graced the covers of newspapers, magazines and occupy a special place in history. They helped shape the world we know today.

They were the who’s who of aviation and featured prominently whilst writing the record books. Whilst Harry Connor’s name is not featured on the incredible and priceless 1930’s Longines display board from this era, Lt Connor’s feats and talents are on another level starting some 93 years ago.

Lt. Connor chose the Longines Weems ref 2106 with the famous 18.69N caliber to use as his trusted navigation timepiece instrument on at least three remarkable record breaking flights – New York to Bermuda, a Trans-Atlantic crossing and a record breaking Round the world flight with Howard Hughes.

Lt Connor, a forgotten aviation hero and master navigator possibly gave us the wrist shot and watch writeup long before today’s Instagram age. His remarkable Longines second-setting watch may be sitting in a collection with the owner unaware of just how special a watch and Flightbird it really is, or it may still be out there awaiting discovery.

[1] 1930 August Aero Digest Lt Connor Navigation on the non-stop flight from New York to Bermuda and return.

[2] Longines / Wittnauer ad from 1930.

[3] Erroll Boyd: World War I Combat Pilot and Aviation Daredevil (historynet.com)

Lt. Harry P. Connor was indeed a master navigator. His use of the Longines Weems ref. 2106 with the 18.69N caliber reminds me of another great navigator, Frederick J. Noonan of Pan American Airways and of course as Amelia Earhart’s navigator on her around-the-world flight in 1937 that ended somewhere near Howland Island.

Noonan also used a Longines Weems second setting watch on the many survey and passenger flights that he flew with Pan American Airways. However, he did not wear the Weems watch on his wrist but had it attached to his bubble octant which he preferred rather than wearing it on his wrist. It is likely that he also had the Weems watch when flying with Earhart.

I would love to hear what other watches Noonan used. Certainly one was a Longines Civil Time Chronometer as mentioned to P.V.H. Weems in a letter to Weems about Noonan’s survey flights in 1935 that was shared in Weems book Air Navigation which I know you know well.

Love your website Andy. It’s filled with remarkable treasures of history.

All the best,

Nicholas Augusta

Greetings Nicholas and apologies for a very belated reply. I sincerely appreciate all of the comments and feedback as it makes it all worthwhile to me when writing. If you have any more information on Noonan would love to write up and of course credit you for the input. A very big thank you. Andy 😉